The 1740 New Londonderry Revival

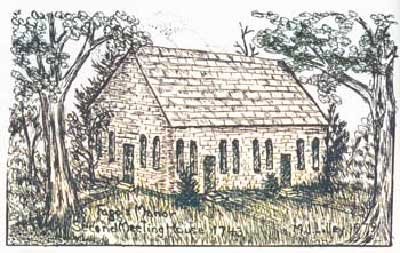

The second meeting place, built to accommodate the growing numbers of people wanting to hear Mr. Blair preach

The 1740 revival at New Londonderry, a lesser-known revival hotspot in the history of the Great Awakening, offers a glimpse into the Holy Spirit’s work in many similar towns in colonial America.

This revival, fuelled by bold and challenging sermons, characterized by intense encounters with God and a renewed emphasis on personal piety, transformed the religious landscape of New Londonderry and left a lasting effect on the community.

This article delves into the historical context surrounding the revival, examines the roles of its principal leaders, explores the spiritual manifestations that marked this period, and examines the revival’s initial and lasting effects. By understanding these facets, we can appreciate the significance of this event in the broader context of American Christian history and gain insights into the dynamics of authentic revival and its effects.

Antecedents of the New Londonderry Revival

The 1740 revival at New Londonderry emerged within a broader context of religious and social change in New England. By the early 18th century, a sense of spiritual decline had settled over many communities. Historical accounts suggest that formalism and a reliance on “good works” for salvation had replaced the enthusiasm and piety of earlier generations. This decline in religious zeal prompted concern among some ministers who sought to rekindle spiritual passion within their congregations.

Adding to this context, the Great Awakening, was already gaining momentum across the American colonies and was also sweeping through Europe during this period. Itinerant preachers like George Whitefield traversed the colonies, delivering fiery sermons that emphasized personal conversion and personal engagement with God, by faith. These factors, combined with the unique social structure of New England towns, created a fertile ground for revivalism in New Londonderry.

The social landscape of New England in the 1740s played a significant role in the spread and impact of religious revivalism. Towns were typically organized around a central meeting house and village green, fostering a strong sense of community and shared religious experiences. This communal structure likely contributed to the rapid dissemination of revivalist teachings and practices.

In New Londonderry, specific concerns about the spiritual state of the community further contributed to the perceived need for revival. Prior to the arrival of Samuel Blair, the congregation of Fagg’s Manor Presbyterian Church exhibited signs of spiritual apathy.

In Blair’s own words, “people were very generally, through the land, careless at heart, and stupidly indifferent about the great concerns of eternity. There was very little appearance of any heart-engagedness in religion; and indeed the wise for the most part were in a great degree asleep with the foolish. It was sad to see with what a careless behaviour the public ordinances were attended, and how people were given to unsuitable worldly discourse on the Lord’s holy day. In public companies, especially at weddings, a vain and frothy lightness was apparent in the deportment of many professors; and in some places, very extravagant follies, as horse-running, fiddling, and dancing, pretty much obtained on those occasions.” (Archibald Alexander’s ‘The Log College.’)

Such behaviours, viewed as distractions from genuine piety, fuelled the Christians’ desire for a spiritual awakening within the community.

Principal Leaders

Samuel Blair, the pastor of Fagg’s Manor Presbyterian Church in New Londonderry, played a central role in the 1740 revival. Blair, a graduate of William Tennent’s Log College, arrived in New Londonderry in 1739 and immediately recognized the spiritual apathy within his congregation. His sermons focused on the need for genuine conversion and a reliance on Christ’s grace for salvation.

Blair’s education at the Log College played a crucial role in shaping his theological perspective and approach to ministry. The Log College, founded by William Tennent Sr., was known for its evangelical emphasis on conversional transformation, experiential piety and its role in training ministers who contributed to the Great Awakening.

The college fostered a revivalist spirit among its students, encouraging them to prioritize personal conversion and personal engagement by faith. This theological background equipped Blair to effectively lead the revival in New Londonderry.

While Blair was away in March 1740, a neighbouring minister “who seemed to be in earnest for the awakening and conversion of secure sinners, and whom I had obtained to preach a Sabbath to my people in my absence, preached to them, I think, on the first Sabbath after I left home. His subject was the dangerous and awful case of such as continue unregenerate and unfruitful under the means of grace.

The text was Luke 13:7 ‘Then said he to the dresser of his vineyard, Behold, these three years I come seeking fruit on this fig tree, and find none; cut it down, why cumbereth it the ground?’ Under that sermon there was a visible appearance of much soul-concern among the hearers, so that some burst out with an audible noise into bitter crying; a thing not known in these parts before.” (From The Log College.)

Upon his return, Blair continued in this vein, and the revival intensified. “And the first sermon I preached after my return to them, was from Matt. vi. 33. “Seek ye first the kingdom of God, and his righteousness.” After opening up and explaining the parts of the text, when, in the improvement, I came to press the injunction in the text upon the unconverted and ungodly, and offered this as one reason among others, why they should now henceforth first of all seek the kingdom and righteousness of God, viz., that they had neglected too long to do so already: this consideration seemed to come and cut like a sword upon several in the congregation; so that while I was speaking upon it, they could no longer contain, but burst out in the most bitter mourning. I desired them as much as possible to restrain themselves from making any noise, that would hinder themselves or others from hearing what was spoken: and often afterwards I had occasion to repeat the same counsel: I still advised people to endeavour to moderate and bound their passions, but not so as to resist or stifle their convictions. The number of the awakened increased very fast; frequently under sermons there were some newly convicted, and brought into deep distress of soul about their perishing estate.” (‘The Awakening in Pennsylvania,’ from Prince’s Christian History, no. 83)

Although not as widely known as figures like George Whitefield or Jonathan Edwards, Blair’s leadership proved crucial in igniting and sustaining the revival in New Londonderry.

Spiritual Manifestations

The 1740 revival was characterized by intense divine encounters and outward expressions of religious fervour. During sermons, people would “burst out with an audible noise into bitter crying.” These manifestations, while alarming to some, were seen by others as evidence of the Holy Spirit’s work in convicting individuals of their sin and drawing them to repentance.

These emotional expressions aligned with the Calvinist theology prevalent at the time. Calvinism emphasized the doctrine of total depravity, the belief that humans are inherently sinful and incapable of saving themselves. The intense emotions displayed during the revival, such as crying and weeping, were interpreted as outward signs of an inner conviction of sin and a recognition of one’s need for God’s grace.

This emphasis on emotional experience and personal conversion distinguished the revival from the more formal and intellectualized religious practices of the time.

The revival also fostered a heightened sense of spiritual awareness and introspection. Individuals grappled with their own mortality and eternal destiny, leading to profound personal transformations.

Place of Prayer

The primary location for prayer and religious gatherings during the 1740 revival was Fagg’s Manor Presbyterian Church. The church, established around 1730, served as the center of religious life for the predominantly Irish settlers of New Londonderry. As the revival gained momentum, the church building, initially constructed in 1730, was replaced with a larger structure in 1742 to accommodate the growing congregation.

Beyond the church walls, religious gatherings and prayer meetings likely extended into homes and other community spaces. The revival’s impact permeated the social fabric of New Londonderry, transforming not only individual lives but also the collective religious experience of the community.

It is important to note the role of meeting houses as centres of community life in colonial New England. Meeting houses served not only as places of worship but also as venues for town meetings, social gatherings, and public discourse. This multifunctional nature of meeting houses likely contributed to the revival’s reach and social impact, as religious fervour spilled over into other aspects of community life.

Initial and Lasting Effects

The 1740 revival had both immediate and long-term effects on the religious landscape of New Londonderry. Initially, the revival brought about a surge in religious fervour and a renewed commitment to Christian living. Church attendance increased dramatically, and the community experienced a period of heightened spiritual awareness.

However, the intensity of the revival proved difficult to sustain. For no apparent reason, the revival in New Londonderry seemed to end as abruptly as it had begun. By the end of the summer of 1740, the initial wave of conversions subsided, and the revival’s momentum waned. This decline reflects a common pattern in the history of religious revivals, which often experience periods of intense fervour followed by a gradual return to more conventional religious practices.

Despite this decline, the revival left a lasting legacy in New Londonderry. It contributed to a greater emphasis on personal piety and heart-engagement with God, which continued to shape the religious character of the community in the years that followed.

Furthermore, the 1740 revival contributed to broader religious awakenings in New England and beyond. The Great Awakening, with its emphasis on personal conversion with divine encounters, had a profound impact on various Christian denominations, particularly the Baptists and Methodists.

Number of Converts

While precise figures are unavailable, the 1740 revival led to a significant number of conversions in New Londonderry. The revival’s impact extended beyond the immediate congregation of Fagg’s Manor Presbyterian Church, reaching neighbouring communities and contributing to the broader Great Awakening movement.

Although the exact number of converts remains unknown, the revival’s influence on the religious landscape suggests a substantial impact on the lives of many individuals in New Londonderry and beyond.

Churches Involved

Fagg’s Manor Presbyterian Church served as the epicentre of the 1740 revival in New Londonderry. The church, with its predominantly Scots-Irish congregation, provided the context for Samuel Blair’s ministry and the outpouring of religious fervour that marked the revival.

While other denominations may have been present in New Londonderry, the Presbyterian Church played the most prominent role in the revival. The revival’s impact likely extended to other Presbyterian congregations in the surrounding region, contributing to the growth and influence of Presbyterianism during the Great Awakening.

The Broader Context of the Great Awakening

The 1740 revival at New Londonderry should be understood within the broader context of the Great Awakening that swept through the American colonies in the 1730s and 1740s. This movement arose as a reaction against the increasing secularization of society and the perceived formalism and complacency within established churches.

Key figures of the Great Awakening included Jonathan Edwards, known for his theological writings and his role in the Northampton revival of 1734-1735, and George Whitefield, a charismatic itinerant preacher whose sermons drew massive crowds and sparked emotional religious experiences.

The Great Awakening emphasized personal conversion, emotional engagement with God by faith, and a rejection of traditional religious hierarchies. The revival in New Londonderry exemplifies these characteristics, demonstrating the widespread influence of the Great Awakening on colonial American religion.

Conclusion

The 1740 revival at New Londonderry stands as a testament to the power authentic revival in shaping individual lives and communities. Driven by the leadership of Samuel Blair and fuelled by the fervour of the Great Awakening, the revival brought about a period of intense spiritual awakening in New Londonderry.

While the initial wave of conversions subsided, the revival’s emphasis on personal piety and living by faith in God left a lasting legacy on the religious landscape of the community and contributed to the broader religious awakenings in New England and beyond.

The revival’s impact extended beyond the immediate community, influencing the development of American religious identity and contributing to the growth of denominations like the Baptists, Presbyterians, Congregationalists and Methodists.

The emotional expressions and personal transformations that characterized the revival offer valuable insights into the dynamics of religious experience and the enduring human search for meaning and connection with the divine.

The 1740 revival at New Londonderry serves as a reminder of the transformative power of true revivals and their enduring influence on American history and culture.

For further research:

The First Great Awakening A comprehensive overview.

On this site:

Introduction

The Great Awakening – Moravians

The Great Awakening – George Whitefield