Welsh Revivals before 1904

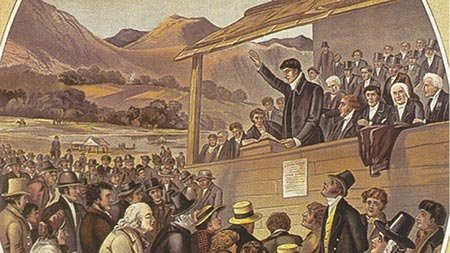

Welsh Revival Meeting

An overview of revivals that occurred in Wales prior to the 1904 outpouring. This article is chapter 3 of H. Elvet Lewis’ ‘With Christ Among the Miners’ entitled ‘The White Line of Revival.’

There are traces of the action of revivals in Wales from the first appearance of Christianity here.

It explains much that is contained in legends of the saints; it has given form to some of the traditions which gather around the life of St. David; it reappears time after time, as at the coming of the little sons of St. Francis and the Lollards, and again at the dawn of Nonconformity, when, in the words of Walter Cradock, ‘the Gospel ran over the mountains between Brecknockshire and Monmouthshire, as the fire in the thatch” – some hundreds of people, filled with good news, were telling it to others.

Welsh Revivals of the 18th Century

The Evangelical Revival of the eighteenth century had two sources: one from within and the other from without. Daniel Rowland became the leader of the native movement. HowelI Harris brought the fire from Oxford, and kept nearer, for a while, to Wesley and to Whitfield. But the two forces were soon merged and the whole movement was infused by the native spirit, assuming national characteristics. The old churches were renewed, new churches had to be formed.

A new nation came out of it. In their work on The Welsh People, Principal Rhys and Sir D. Brynmor Jones remarked: “In 1730 the Welsh-speaking people were probably as a whole the least religious and most intellectually backward in England and Wales. By 1830 they had become the most earnest and religious people in the whole kingdom.”

While making some allowance for the exigencies of an antithesis, this statement, in its substance, is scarcely to be disputed. True, this result was not the fruit of the revival alone. The revival, which started in 1737, was followed by a great educational reform which was both secular and religious. A new literature had been born and a new social outlook had been gained. All these forces, building on the revival, helped to make Wales what it is described as having become by 1830.

Welsh Revivals of the 19th Century

During the nineteenth century there were several revivals – all of them national, in a modified sense, and one of them undoubtedly so. A brief sketch of the more remarkable of these will show how certain traits are transmitted from one to another, as by a hereditary law, and how these have again reappeared in the latest of all.

Every lover of Mount Snowdon knows Beddgelert and the Vale of Gwynant. In a farmhouse in the vale, one Sunday in August, 1817, a humble “exhorter’ – Richard Williams by name – was expected to take a service. He came but the congregation was scanty. John Elias was preaching that day at Tremadoc, and the fame of the great preacher had, in spite of the distance, reduced the exhorters numbers almost to the lowest point.

There was a hardness in the atmosphere too that made the discouraged preacher’s task still more difficult. The people who were present envied those who had gone to hear John Elias. They sat before Richard Williams, but their ears were at Tremadoc. He struggled through the lesson and prayer and then took up the sermon, gradually warming to his task. And then, somewhere in the sermon, the inexplicable happened. Preacher and congregation were transformed.

The humble “exhorter” stood forth a prophet of the Most High, in Pentecostal glow, and the house was filled with the Pentecostal cry of awakened souls. And in that Vale of Gwynant, that Sabbath evening, men said awe-stricken: “We never saw it on this fashion.” Within five weeks of that day there was scarcely a house in the vale but the breath of prayer had filled it.

Revival at Beddgelert

It reached the village of Beddgelert in its own way. On a Sunday in September a class of young girls was reading the crucifixion chapter in St. John’s gospel. The teacher was a young woman of devout, earnest mind. As they read the story, verse by verse in turn, something come into the narrative unfelt before. Silent tears stole down the cheek of each reader, and a sense of awe took them one and all.

At the close, when the school was, as usual, being publicly catechized by one of the male teachers, his own spirit suddenly took fire in warning the young people against some local fair of evil repute.

A line out of one of Williams of Pantycelyn’s Welsh hymns seemed to possess him, “Gods grasp is the surest”; and as he repeated it more than once, the feeling which had melted and awed the young women’s class affected the whole school. Not many days after, the chapel had become the scene of convictions and conversions. “Some were praying for pardon, kneeling on the floor of the pew; others, standing on a form, were uttering praise for Gods mercy; some were marching to and fro, singing with their whole soul the song of deliverance.”

It was a season of rejoicing. One day even, while busy hay making, someone started singing a hymn to himself, another caught it up, and another, until the whole band of haymakers, forgetful for a while of their toil, became a band of praying, singing worshippers. This revival continued for three or four years and its influence on the Snowdon district has been carried on to this day. It spread to other parts, but not generally.

An old survivor, being asked whether he could recall any signs preceding and heralding this revival, replied that he could remember nothing; “except,” that the air for months seemed full of brotherly kindness and love.”

Dolyddelen is far on the other side of Snowdon from Beddgelert, between Festiniog and Bettws-y-coed. Some twelve months previous to the Beddgelert incident, Williams of Wern was preaching here on the work of the Holy Spirit. In the course of his remarks he said: “What if you were to consent to have Him to save the whole of this parish? ‘Ah, but how can we have Him?’

Well, hold prayer-meetings through the whole parish; go from house to house – to every house that will open its door. Make it the burden of every prayer that God should come here to save. If God has not come by the time you have gone through the parish once, go through it again; but if you are in earnest in your prayers, you shall not go through half the parish before God has come to you.” The seed was sown, but apparently it took no root, save in one unlikely soul.

Among those attracted to hear the famous preacher was one woman, old, and lonely and irreligious. She was accustomed in her cottage to use the light of a rush candle, but for a prayer-meeting she felt that nothing poorer than a wax candle would do. Next morning she bought two, to be ready in time. But the weary months passed and no prayer-meeting called at her lowly door. She went at last to the shop where she had purchased the two wax candles and asked diffidently, “When is the prayer-meeting coming to my house?”

The prayer-meeting which Mr. Williams of Wern said was to go from house to house.” The shopkeeper felt rebuked, but answered off-handedly, “Oh! they care very little what anybody says.” “Well, indeed, I bought two candles nearly a year ago, and have gone to bed many a time in the dark, leaving them unburnt, lest the meeting should come and find me without a candle.”

The word struck home; he told it to the church; the pilgrim prayer meeting was started, and the preacher’s prophecy fulfilled. It would be almost enough to say of this revival that it brought to Christ, amongst other men of note, one of the most eloquent of all the preachers of Wales, John Jones of Taly Sarn-“the peoples preacher,” as he was affectionately called.

1829, 1839, 1849, 1859 – these four dates followed in such rhythmical order, with a decade between each, that they had almost produced in Wales a mild superstition. When 1869 passed, and then 1879, without any striking recurrence, there was on the part of many a real disappointment. But other people have fallen into the foolishness of dates.

The first of the four spread far and wide. It was accompanied by a good deal of physical manifestation of joy – shouting, leaping, and dancing – so much so as to make their English co-religionists anxious for the good name of religion. There is a tradition that Rowland Hill being sent down in the interest of sobriety, was himself so captivated as to forget to deliver his reproof. It is certain that reports make these scenes worse from a distance than they really are.

Religious gossip is as loose as any other gossip. That there have been extravagances we may believe from some of last years incidents, but these, if they somewhat marred the effect, left a valuable balance in favor. The contemporary records in the magazines of the vernacular provide ample evidence of a deep and lasting revival on the eve of the Reform Bill.

A temperance movement preceded the Revival of 1839. The first advocates of total abstinence were not only subjected to violent attacks in the press and on the platform, but literally persecuted. In Montgomeryshire some even tasted the cup of martyrdom and so helped to defeat the malice of the foe. In the wake of this – or indeed in part parallel with it – came the religious renaissance, not with sound of tabret and athletic joy as in 1829, but intense, silent, almost somber.

But it has been remarked that it was a very small percentage of those received into the churches then who went back. It is interesting to add that the immediate origin of the revival, apparently, was the visit of a Welsh minister from America, the Rev. B. W. Chidlaw.

The outburst in 1849 was largely due to the cholera scare. It bore the taint of fear. Thousands hurried into the churches, more particularly in populous centres, as in Glamorganshire. But “because they had no root, they withered away” in too many instances. Still, it is certified that many brought in through fear remained to learn the truth in love and live lives of faithful service. There are three gates into the Holy City from the north as well as from the south.

The revival of 1859-60 was more world wide, taking Wales on its way. It had already accomplished great things in America when a Wesleyan Methodist preacher, the Rev. Humphrey Jones, returning home to Wales, and to his native village – Tre’rddol, North Cardiganshire – began to hold mission services early in 1858. The birth of a revival seems always to be in some sequestered nook, to be nursed for weeks among the silence of the hills, or in some creek beside the sea.

The fire spread from hamlet to hamlet, and to the larger towns it was only a report for months. The young Welshman from America found a comrade in the Rev. David Morgan, Calvinistic Methodist preacher. They preached prayer; they practiced it; they seemed to compel it. There was no special gift in either to mark them out for the work which God had called them to do.

The health of the former broke down; the latter retired into the rank of ordinary preachers after the season of blessing. But during Gods season, they swept every audience into prayer. The churches of all denominations were moved to the core; very few districts were left unvisited by the power, but there were some. It bequeathed a blessing and a memory which lasted until 1904-5 came to take its place in the nations living heart.

The interval of forty-five years between the two Pentecostal seasons was not without its occasional showers of blessing, though they were mostly local and personal. The most noteworthy of these is associated with the name of the Rev. Richard Owen, Calvinistic Methodist preacher. It was spread over the years before and after 1880 – contemporaneously with some of the first evangelistic efforts of the Salvation Army. His methods were all his own.

He was the least imitable of all that have moved the heart of Wales. He preached as tbough he were conversing all the time with the open Bible, scarcely lifting his eyes from it, but what conversations they were! When he passed away in 1887,-“ in the mid-journey of our life” he could number, it is said, as the record of his few flame-girt years, no Iess than thirteen thousand souls brought to Christ. “He had the privilege and the happiness,” said Principal Edwards, “of setting at noon.”

One of the young workers of that period in South Wales was Miss Rosina Davies. And all through the years, up to the present, she has carried on a constant mission among all the churches. Even in the colder years her meetings often become reminiscent of 1859, and prophetic of 1904.

More particularly among English residents in Glamorganshire and Monmouthshire, the “Foreword Movement” of the Calvinistic Methodists – with Dr. John Pugh for its leader and Seth Joshua and others for its evangelists – had during recent years stirred a large amount of evangelistic zeal, and as will be seen in the course of the narrative, direct influences from this movement touched Evan Roberts.

Nor should the eager but brief mission of the Rev. John Evans (Eglwysbach), the evangelist of Wesleyan Methodism in the Rhondda Valley, be forgotten. Death removed him in the midst of his task and perhaps the immediate results of his efforts were disappointing, but he belonged to the whole nation. A child of the 59 Revival, he was a life long revivalist and had been frequently given a foretaste of the harvest joy of 1905, though he did not live to mingle with the reapers.

We cannot pretend to have attempted more than to point out, in this series of memorable dates and episodes, the arches of the bridge spanning the gulf of the generations. It proves the proneness of Wales to revival. The birth of each of the four great divisions of the Free Churches has been hailed by a revival- Baptists and Independents at the beginning of the seventeenth century, the Calvinistic Methodists in the middle of the eighteenth, and the Wesleyan Methodists at the dawn of the nineteenth.

Nor should great individual contributions from the Church of England be left out of account; especially the work, both in sermon and song, of Vicar Pritchard, contemporary of the early Independents, who was followed by Griffith Jones of Llanddowror, evangelist and educationalist.

It is not too much to say that an air of wistfulness pervades the land at almost all times – either in retrospect of a past revival, or in prospect of a coming revival. It is either a charmed memory-“ We were like them that dream; then was our mouth filled with laughter, and our tongue with singing: then said they among the heathen, The Lord hath done great things for them”; or else it is a sorrowing, deepening appeal, “It is time for Thee, Lord, to work: for they have made void Thy law.”

The wistfulness, on occasions, becomes almost, if not altogether, prophetic. It is not well to strain the language of heart’s desire, and compel the event of today to exalt the eloquent earnest word of yesterday into prophecy, but such forecasts prove at least what currents of warmth are in the upper air.

We select three illustrations from among several more that might be given. Some four years previous to the epiphany of the present revival a saintly old man, on his death bed and within a few days of dying in his Lords peace, remarked that a mighty revival would visit the land before long.

“And mark my words, it will come this time from the south; the former came the direction of the north (referring to 1859-1860), but the next will be from the south.” This was his interpretation of a vision he had seen of white horses travelling northwards from the south….

One evening in August, 1904, returning home from a service in a village chapel, slowly, over a long steep road, under the shadow of an oak forest that fitfully swayed to the soft night wind, the present writer was considerably exercised by a remark which his companion made: “Do you know, I think we are very near something very wonderful? Some great things are going to happen in the churches very soon!” He could not explain to me why he cherished this assured hope.

He felt it, he said. The speaker had lived all his life in one of those quiet rural neighborhoods which seem to be a little world in themselves, moving in their own orbit. I was interested and moved at the time, but much more so as the first news of the revival, some three months later, began the fulfilment of his anticipation. “And there were shepherds abiding in the field, keeping watch over their flock by night” – they were Gods first audience when. the Gospel was sung by the firstborn sons of light.

At the commencement of 1903 the late Dean Howell published a kind of New Years epistle to the nation. In it he dwelt solemnly on the fact that a revival must be near, or else the nation would go back. They were about to pass through a chill and wasting period of indifference, of formalism, of defeat, unless God in His mercy would visit them with a Dayspring from on High.

“Take note,” he wrote, “if I knew this to be my last message to my fellow countrymen, before I am summoned to Judgement, the light of eternity already breaking on me, this is what I would say: that the chief need of my beloved nation at this moment is – A spiritual revival through a powerful outpouring of the Holy Ghost.” He died, January 15th, just as his letter was being read.

For further reading;

Daniel Rowland and the Welsh 18th Century Revival