Awakening in Pennsylvania – 1744

Samuel Blair

SAMUEL BLAIR, Minister at New Londonderry, to MR. PRINCE, Minister at Boston, August 6th, 1744, in PRINCE’S CHRISTIAN HISTORY, No. 83.

REVEREND SIR,—That it may the more clearly appear that the Lord has indeed carried on a work of true religion among us of late years, I conceive it will be useful to give a brief general view of the state of religion in these parts before this remarkable season.

The State of the church before the revival

I doubt not then but there were some sincerely religious people up and down; and there were, I believe, a considerable number in the several congregations, pretty exact, according to their education, in the observance of the external forms of religion, not only as to attendance upon public ordinances on the Sabbaths, but also as to the practice of family worship, and perhaps secret prayer too.

But with these things the most part seemed, to all appearance, to rest contented, and to satisfy their consciences just with a dead formality in religion. If they performed these duties pretty punctually in their seasons, and as they thought with a good meaning, out of conscience, and not just to obtain a name for religion among men, then they were ready to conclude that they were truly and sincerely religious.

A very lamentable ignorance of the main essentials of true practical religion, and the doctrines nextly relating thereunto, very generally prevailed. The nature and necessity of the new birth was but little known or thought of. The necessity of a conviction of sin and misery, by the Holy Spirit opening and applying the law to the conscience, in order to a saving closure with Christ, was hardly known at all to the most.

It was thought that if there was any need of a heart-distressing sight of the soul’s danger, and fear of Divine wrath, it was only needful for the grosser sort of sinners; and for any others to be deeply exercised this way, (as there might sometimes be before some rare instances observable) this was generally looked upon to be a great evil and temptation that had befallen those persons. The common names for such soul-concern were, melancholy, trouble of mind, or despair.

These terms were in common, so far as I have been acquainted, indifferently used as synonymous; and trouble of mind was looked upon as a great evil, which all persons, that made any sober profession and practice of religion, ought carefully to avoid. There was scarcely any suspicion at all, in general, of any danger of depending upon self-righteousness, and not upon the righteousness of Christ alone for salvation.

Papists and Quakers would be readily acknowledged guilty of this crime; but hardly any professed Presbyterian. The necessity of being first in Christ by a vital union, and in a justified state, before our religious services can be well-pleasing and acceptable to God, was very little understood or thought of; but the common notion seemed to be, that if people were aiming to be in the way of duty as well as they could, as they imagined, there was no reason to be much afraid.

According to these principles, and this ignorance of some of the most soul-concerning truths of the Gospel, men were very generally through the land careless at heart, and stupidly indifferent about the great concerns of eternity. There was very little appearance of any heart-engagedness in religion; and indeed the wise, for the most part, were in a great degree asleep with the foolish.

It was sad to see with what a careless behaviour the public ordinances were attended, and how people were given to unsuitable wordly discourse on the Lord’s-day. In public companies, a vain and frothy lightness was apparent in the deportment of many professors.

Thus religion lay as it were a-dying, and ready to expire its last breath of life in this part of the visible church; and it was in the spring, in the year 1740, when the God of salvation was pleased to visit us with the blessed effusions of his Holy Spirit in an eminent manner. The first very open and public appearance of this gracious visitation in these parts, was in the congregation which God has committed to my charge.

The Arrival of Mr. Samuel Blair

This congregation has not been erected above fourteen or fifteen years from this time; the place is a new settlement, generally settled with people from Ireland, (as all our congregations in Pennsylvania, except two or three, chiefly are made up of people from that kingdom.)

I am the first minister they have ever had settled in the place; having been regularly liberated from my former charge in East-Jersey, above an hundred miles north-eastward from hence, (the rev. presbytery of New Brunswick, of which I had the comfort of being a member, judging it to be my duty, for sundry reasons, to remove from thence.)

At the earnest invitation of the people here, I came to them in the beginning of November 1739, accepted of a call from them that winter, and was formally installed and settled among them as their minister in April following. There was some hopefully pious people here at my first coming, which was a great encouragement and comfort to me.

I had some view and sense of the deplorable condition of the land in general; and accordingly the scope of my preaching through that first winter after I came here, was mainly calculated for persons in a natural unregenerate state. I endeavoured as the Lord enabled me, to open up and prove from his word, the truths which I judged most necessary for such as were in that state to know and believe, in order to their conviction and conversion.

Beginnings of the Awakening in Pennsylvania

I endeavoured to deal searchingly and solemnly with them: and through the blessing of God, I had knowledge of four or five brought under deep convictions that winter.

In the beginning of March I took a journey into East-Jersey, and was abroad for two or three Sabbaths: a neighbouring minister, who seemed to be earnest for the awakening and conversion of secure sinners, and whom I had obtained to preach a Sabbath to my people in my absence, preached to them, I think, on the first Sabbath after I left home: his subject was the dangerous and awful case of such as continue unregenerate and unfruitful under the means of grace.

The text was Luke xiii. 7. “Then said he to the dresser of his vineyard; behold, these three years I come seeking fruit on this fig-tree, and find none; cut it down, why cumbereth it the ground? “ Under that sermon there was a visible appearance of much soul concern among the hearers; so that some burst out with an audible noise into bitter crying (a thing not known in these parts before.)

After I had come home, there came a young man to my house under deep trouble about the state of his soul, whom I had looked upon as a pretty light merry sort of a youth; He told me that he was not any thing concerned about himself in the time of hearing the above-mentioned sermon, nor afterwards, till the next day he went to his labour, which was grubbing, in order to clear some new ground: the first grub he set about was a pretty large one with a high top.

When he had cut the roots, as it fell down, these words came instantly to his remembrance, and as a spear to his heart, “Cut it down, why cumbereth it the ground? “ so, thought he, must I be cut down by the justice of God for the burning of hell, unless I get into another state than I am now in. He thus came into very great and abiding distress, which, to all appearance, has had a happy issue; his conversation being to this day as becomes the gospel of Christ.

The news of this very public appearance of deep soul-concern among my people met me an hundred miles from home: I was very joyful to hear of it, in hopes that God was about to carry on an extensive work of converting grace amongst them. And the first sermon I preached after my return to them, was from Matt. vi. 33. “Seek ye first the kingdom of God, and his righteousness. “

After opening up and explaining the parts of the text, when, in the improvement, I came to press the injunction in the text upon the unconverted and ungodly, and offered this as one reason among others, why they should now henceforth first of all seek the kingdom and righteousness of God.

Viz., that they had neglected too long to do so already: this consideration seemed to come and cut like a sword upon several in the congregation; so that while I was speaking upon it, they could no longer contain, but burst out in the most bitter mourning.

I desired them as much as possible to restrain themselves from making any noise, that would hinder themselves or others from hearing what was spoken: and often afterwards I had occasion to repeat the same counsel: I still advised people to endeavour to moderate and bound their passions, but not so as to resist or stifle their convictions. The number of the awakened increased very fast; frequently under sermons there were some newly convicted, and brought into deep distress of soul about their perishing estate.

Our Sabbath assemblies soon became vastly large: many people from almost all parts around inclining very much to come where there was such appearance of the divine power and presence. I think there was scarcely a sermon or lecture preached here through that whole summer, but there were manifest evidences of impressions on the hearers.

Revival Manifestations during the Awakening in Pennsylvania

Many times the impressions were very great and general; several would be overcome and fainting; others deeply sobbing, hardly able to contain: others crying in a most dolorous manner; many others more silently weeping; and a solemn concern appearing in the countenances of many others. And sometimes the soul exercises of some (though comparatively but very few) would so far affect their bodies as to occasion some strange unusual bodily motions.

I had opportunities of speaking particularly with a great many of those, who afforded such outward tokens of inward soul-concern in the time of public worship and hearing of the word: indeed many came to me of themselves in their distress, for private instruction and counsel; and I found, so far as I can remember, that with by far the greater part their apparent concern in public was not just in a transient qualm of conscience, or merely a floating commotion of affections; but a rational fixed conviction of their dangerous perishing estate.

They could generally offer as a convictive evidence of their being in an unconverted miserable estate, that they were utter strangers to those dispositions, exercises, and experiences of soul in religion, which they heard laid down from God’s word, as the inseparable characters of the truly regenerate people of God.

Even such as before had something of the form of religion; and I think the greater number were of this sort; and several had been pretty exact and punctual in the performance of outward duties: they saw they bad been contenting themselves with the form without the life and power of godliness; and that they had been taking peace to their consciences from, and depending upon their own righteousness, and not the righteousness of Jesus Christ.

In a word, they saw that true practical religion was quite another thing than they had conceived it to be, or had any true experience of. There were likewise many throughout the land brought under deep distressing convictions that summer who had lived very loose lives, regardless of the very externals of religion. In this congregation I believe there were very few that were not stirred up to some solemn thoughtfulness and concern more than usual about their souls.

The general carriage and behaviour of people was soon very visibly altered. Those awakened were much given to reading in the holy Scriptures and other good books. Excellent books that had lain by much neglected, were then much perused, and lent from one to another: and it was a peculiar satisfaction to people to find how exactly the doctrines they heard daily preached, harmonized with the doctrines maintained and taught by great and godly men in other parts and former times.

Preaching Content during the Awakening in Pennsylvania

The subjects of discourse almost always when any of them were together, were the matters of religion and great concerns of their soul. All unsuitable, worldly, vain discourse on the Lord’s day seemed to be laid aside among them; indeed, for any thing that appeared, there seemed almost an universal reformation in this respect in our public assemblies on the Lord’s day.

There was an earnest desire in people after opportunities for public worship and hearing the word. I appointed in the spring to preach every Friday through the summer when I was at home, and those meetings were well attended; and at several of them the power of the Lord was remarkably with us.

The main scope of my preaching through that summer was laying open the deplorable state of man by nature since the fall, our ruined exposed case by the breach of the first covenant, and the awful condition of such as were not in Christ, giving the marks and characters of such as were in that condition; and moreover, laying open the way of recovery in the new covenant through a Mediator, with the nature and necessity of faith in Christ the Mediator, &c.

I laboured much on the last mentioned heads; that the people might have right apprehensions of the gospel method of life and salvation. I treated much on the way of sinners closing with Christ by faith, and obtaining a right peace to an awakened wounded conscience.

(This was to show) that persons were not to take peace to themselves on account of their repentings, sorrows, prayers, and reformations; nor to make these things the grounds of their adventuring themselves upon Christ and his righteousness, and of their expectations of life by him.

And that neither were they to obtain or seek peace in extraordinary ways, by vision, dreams, or immediate inspirations, but, by an understanding view, and believing persuasion of the way of life, as revealed in the gospel through the suretyship, obedience and sufferings of Jesus Christ; with a view of the suitableness and sufficiency of that mediatory righteousness of Christ for the justification and life of law-condemned sinners.

Thereupon, freely accepting him for their Saviour, heartily consenting to, and being well pleased with, the way of salvation, and venturing their all upon his mediation, from the warrant and encouragement afforded of God thereunto in his word, by his free offer, authoritative command, and sure promise to those that so believe. I endeavoured to show the fruits and evidences of a true faith, &c.

In some time many of the convinced and distressed afforded very hopeful satisfying evidence that the Lord had brought them to a true closure with Jesus Christ; and that their distresses and fears had been in a great measure removed in a right gospel-way, by believing in the Son of God. Several of them had very remarkable and sweet deliverances this way.

It was very agreeable to hear their accounts how that when they were in the deepest perplexity and darkness, distress and difficulty, seeking God as poor condemned hell-deserving sinners, the scene of recovering grace through a Redeemer has been opened to their understandings with a surprising beauty and glory, so that they were enabled to believe in Christ with joy unspeakable and full of glory.

It appeared that most generally the Holy Spirit improved for this purpose, and made use of some one particular passage or other of the Holy Scripture that came to their remembrance in their distress, some gospel offer or promise, or some declaration of God directly referring to the recovery and salvation of undone sinners by the new covenant. But with some it was otherwise: they had not any particular place of scripture more than another in their view at the time.

Those who met with such a remarkable relief; as their account of it was rational and scriptural, so they appeared to have had at the time, the attendants and fruits of a true faith; particularly, humility, love, and an affectionate regard to the will and honour of God.

Much of their exercise was in self abasing and self-loathing; and admiring the astonishing condescension and grace of God towards such vile and despicable creatures that had been so full of enmity and disaffection to him: they freely and sweetly with all their hearts chose the way of his commandments; their inflamed desire was to live to him forever according to his will, and to the glory of his name.

There were others that had not had such remarkable relief and comfort, who yet I could not but think were savingly renewed, and brought truly to accept of the rest upon Jesus Christ, though not with such a degree of liveliness and liberty, strength and joy: and some of those continued for a considerable time after, for the most part, under a very distressing suspicion and jealousy of their case.

I was all along very cautious of expressing to people my judgment of the goodness of their states, excepting where I had pretty clear evidences from them of their being savingly changed; and yet they continued in deep distress, casting off all their evidences: sometimes in such cases, I have thought it needful to use greater freedom that way than ordinary; but otherwise, I judged that it could be of little use, and might easily be hurtful.

Beside those above spoken of, whose experience of a work of grace was in a good degree clear and satisfying, there were some others (though but very few in this congregation that I knew of) who, having very little knowledge or capacity, had a very obscure and improper way of representing their case in relating how they had been exercised.

They would chiefly speak of such things as were only the effects of their soul-exercise upon their bodies from time to time, and some things that were purely imaginary: which obliged me to be at much pains in my enquiries before I could get any just ideas of their case.

I would ask them, what were the thoughts, the views and apprehensions of their minds, and exercise of their affections, (at such times when they felt, perhaps, a quivering come over them, as they had been saying, or a faintness, or thought they saw their hearts full of some nauseous filthiness.

Or when they felt a heavy weight or load at their hearts, or felt the weight again taking off and a pleasant warmness rising from their hearts, as they would probably express themselves,) which might be the occasions or causes of these things they spoke of.

And then, when with some difficulty I could get them to understand me, some of them would give a pretty rational account of solemn and spiritual exercises: and upon a thorough careful examination this way, I could not but conceive good hopes of some such persons.

But there were, moreover, several others, who seemed to think concerning themselves that they were under some good work, of whom yet I could have no reasonable ground to think that they were under any hopeful work of the Spirit of God.

As near as I could judge of their case from all my acquaintance and conversation with them, it was much to this purpose: they believed there was a good work going on; that people were convinced, and brought into a converted state; and they desired to he converted too: they saw others weeping and fainting, and heard people mourning and lamenting, and they thought if they could be like these it would be very hopeful with them.

Hence, they endeavoured just to get themselves affected by sermons, and if they could come to weeping, or get their passions so raised as to incline them to vent themselves by cries, now they hoped they were got under convictions, and were in a very hopeful way; and afterwards, they would speak of their being in trouble, and aim at complaining of themselves, but seemed as if they knew not well how to do it, nor what to say against themselves.

And then they would be looking and expecting to get some texts of scripture applied to them for their comfort; and when any scripture text which they thought was suitable for that purpose came to their minds, they were in hopes it was brought to them by the Spirit of God, that they might take comfort from it.

And thus, much in such a way as this, some appeared to be pleasing themselves just with an imaginary conversion of their own making. I endeavoured to correct and guard against all such mistakes so far as I discovered them, in the course of my ministry; and to open up the nature of a true conviction by the Spirit of God, and of a saving conversion.

Further Observations on Revival Influences

Thus I have given a very brief account of the state and progress of religion here through that first summer after the remarkable revival of it among us. Towards the end of that Summer there seemed to be a stop put to the farther progress of the work as to the conviction and awakening of sinners; and ever since there have been very few instances of persons convinced.

It remains then, that I speak something of the abiding effects and after-fruits of those awakenings and other religious exercises which people were under during the above-mentioned period. Such as were only under some slight impressions and superficial awakenings, seem in general to have lost them all again without any abiding hopeful alteration upon them.

They seem to have fallen back again into their former carelessness and stupidity, and some that were under pretty great awakenings, and considerably deep convictions of their miserable state, seem also to have got peace again to their consciences, without getting it by a true faith in the Lord Jesus, affording no satisfying evidence of their being savingly renewed.

But, through the infinite rich grace of God (and blessed be his glorious name!) there is a considerable number who afford all the evidence that can be reasonably expected and required for our satisfaction in the case, of their having been the subjects of a thorough saving change.

(Except in some singular instances of behaviour, alas for them, which proceed from, and shew the sad remains of original corruption even in the regenerate children of God while in this imperfect state:) their walk is habitually tender and conscientious, their carriage towards their neighbours just and kind, and they appear to have an agreeable peculiar love one for another, and for all in whom appears the image of God.

Their discourses of religion, their engagedness and disposition of soul in the practice of the immediate duties and ordinances of religion, all appear quite otherwise than formerly. Indeed, the liveliness of their affections in the ways of religion is much abated in general, and they are in some measure humbly sensible of this, and grieved for it, and are carefully endeavouring still to live unto God; much grieved with their imperfections and the plagues they find in their own hearts.

Frequently they meet with some delightful enlivenings of soul; and particularly our sacramental solemnities for communicating in the Lord’s Supper have generally been very blessed seasons of enlivening and enlargement to the people of God. There is a very evident and great increase of Christian knowledge with many of them.

We enjoy in this congregation the happiness of a great degree of harmony and concord; scarcely any have appeared with open opposition and bitterness against the work of God among us and elsewhere up and down the land; though there are pretty many such in several other places through the country: some indeed, in this congregation, but very few, have separated from us, and joined with the ministers who have unhappily opposed this blessed work.

It would have been a great advantage to this account had I been careful in time to have written down the experiences of particular persons; but this I neglected in the proper season. However, I have more lately noted down an account of some of the soul exercises and experiences of a young woman, but I judge it proper to conceal her name, because she is yet living. I was very careful to be exact in the affair, both in my conversing with her, and writing the account she gave me of herself, immediately after.

And though I do not pretend to give her very words for the most part, yet I am well satisfied I do not misrepresent what she related. The account then is thus: she was first brought to some solemn thoughtfulness and concern about her soul’s case, by seeing others so much concerned about their souls when she saw people in deep distress about the state of their souls, she thought with herself, how unconcerned she was about her own.

And though she thought that she had not been very guilty of great sins, yet she feared she was too little concerned about her eternal well-being: and then the sermons she heard made her still more uneasy about her case; so that she would go home on the Sabbath evenings pretty much troubled and cast down; which concern used to abide with her for a few days after.

Still, towards the end of the week she would become pretty easy; and then, by hearing the Word on the Sabbath-days, her uneasiness was always renewed for a few days again. And thus it fared with her, till one day, as she was hearing a sermon preached from Heb. iii, 16, “Today if you will hear his voice, harden not your hearts; “ the minister in the sermon spoke to this effect.

“How many of you have been hearing the Gospel for a long time, and yet your hearts remain always hard, without being made better by it: the Gospel is the voice of God, but you have heard it only as the voice of man, and not the voice of God, and so have not been benefited by it. “ These words came with power to her heart.

She saw that this was her very case: and she had an awful sense of the sin of her mis-improvement of the Gospel, of her stupidity, hardness, and unprofitableness under hearing of the Word of God: she saw that she was hereby exposed to the sin-punishing justice of God, and so was filled with very great fear and terror: but she said there was no other sin at that time applied to her conscience, neither did she see herself as altogether without Christ.

This deep concern on the fore-mentioned account stuck pretty close by her afterwards. There was a society of private Christians to meet in the neighbourhood some day after in the same week, for reading, prayer, and religious conference: she had not been at a society of that kind before, but she longed very much for the time of their meeting then, that she might go there: and while she was there, she got an awful view of her sin and corruption, and saw that she was without Christ and without grace.

Her exercise and distress of soul was such, that it made her for a while both deaf and blind; but she said she had the ordinary use of her understanding, and begged that Christ might not leave her to perish; for she saw she was undone without him. After this she lived in bitterness of soul: and at another time she had such a view of her sinfulness, of the holiness and justice of God, and the danger she was in of eternal misery, as filled her with extreme anguish.

Had it not been that she was supported by an apprehension of God’s all-sufficiency, she told me she was persuaded she should have fallen immediately into despair. She continued for some weeks in great distress of spirit, seeking and pleading for mercy without any comfort, until one Sabbath evening, in a house where she was lodged during the time of a sacramental solemnity, while the family were singing the eighty-fourth psalm, her soul conceived strong hopes of reconciliation with God through Jesus Christ.

She had such apprehensions of the happiness of the heavenly state, that her heart was filled with joy unspeakable and full of glory; she sung with such elevation of soul, as if she had sung out of herself, as she expressed it.

She thought at the time, it was as if the Lord had put by the veil, and shewed her the open glory of heaven: she had very enlarged views of the sufficiency of Christ to save: she was clearly persuaded to the fullest satisfaction, that there was merit enough in him to answer for the sins of the most guilty sinner; and she saw that God could well be reconciled to all elect sinners in his Son; which was a most ravishing delightful scene of contemplation to her.

After this she continued very much under grievous dejections for about two years, and yet enjoyed considerable sweetness and comfort at times: she often came to hear sermons with a desire to get clearly convinced of her being yet in a Christless state, and with a formed resolution to take and apply to herself what might be said in the sermon to the unconverted; but most commonly she returned very agreeably disappointed.

She would generally hear some mark of grace, some evidence of a real Christian laid down, which she could lay claim to, and could not deny; and thus she was supported and comforted from time to time. During that two years’ space it was still with much fear and perplexity that she adventured to communicate in the Lord’s Supper; but she could not omit it; and she always found some refreshing sweetness by that ordinance.

After she had been so long under an almost alternate succession of troubles and supports, the Sun of Righteousness at last broke out upon her, to the clear satisfaction and unspeakable ravishment of her soul, at a communion table.

There her mind was let into the glorious mysteries of redemption with great enlargement: while she meditated on the sufferings of the Lord Jesus, she thought with herself he was not just a man who suffered so for sinners, but infinitely more than a man, even the Most High God, the eternal Son equal with the Father: and she saw his being God put an infinite lustre and value upon his sufferings as man; her heart was filled with a most unutterable admiration of his person, his merit, and his love.

She was enabled to believe in him with a strong self-evidencing faith; and when she thought that he had suffered for her sins, that she was the very person who by her sins had occasioned his sufferings, and brought agony and pain upon him: the consideration of this filled her with the deepest abhorrence of her sins, and most bitter grief for them; she said she could have desired with all her heart to have melted and dissolved her body quite away in that very place, in lamentation and mourning over her sins.

After this enjoyment her soul was generally delighting in God, and she had much of the light of his countenance with her: and O, her great concern still was, how she might live to the Lord, how she might do anything for him, and give honour to him: the Lord condescended to be much with her by his enlivening and comforting presence, and especially sacramental seasons were blessed and precious seasons to her.

At one of those occasions, she was in a sweet frame meditating on the blood and water that issued from the wound made by the spear in her Saviour’s side: she thought, as water is of a purifying cleansing nature, so there was sanctifying virtue as well as justifying merit in the Lord Jesus; and that she could no more be without the water, his sanctifying grace, to cleanse her very polluted soul, than she could be without his blood to do away her guilt: and her heart was much taken up with the beauty and excellency of sanctification.

At another time, a communion solemnity likewise, she was very full of delight and wonder with the thoughts of electing love; how that God had provided and determined so great things for her before ever she had a being. And a very memorable enjoyment she had at another time, on Monday after a communion Sabbath, when these words came to her mind, “The Spirit and the Bride say, come, and let him that is a-thirst come, and whosoever will, let him take the water of life freely. “

The glory and delight let in upon her soul by these words was so great, that it quite overcame her bodily frame: she said it seemed to her that she was almost all spirit, and that the body was quite laid by; and she was sometimes in hopes that the union would actually break, and the soul get quite away: she saw much at that time into the meaning of her Lord in those words, “Because I live, ye shall live also. “

Another Account of Revival Influences

About a time of sickness she had had, concerning which I had inquired of her, she told me, she expected pretty much to die then, and was very joyful at the near prospect of her change, and sensibly grieved to find herself recover again; chiefly because that while she lived here she was so frail and sinful, and could do so little for the Lord’s honour.

I was with her in the time of that sickness, and indeed I scarcely ever saw one appear to be so fully and sweetly satisfied under the afflicting hand of God; she manifestly appeared to lie under it with a peaceful serenity and Divine sweetness in her whole soul. In a word, her whole deportment in the world bespeaks much humility and heavenliness of spirit.

One of our Christian friends, a man about fifty years of age, was removed from us by death in the beginning of May last, of whom I can give some broken imperfect account, which perhaps may be of some use. His name was Hans Kirkpatrick: he was a man of a pretty good understanding, and had been, I believe, a sober professor for many years, though he had not been very long in America.

After the work of religion, begun so powerfully amongst us, I found in conversation with him, that he believed it to be a good work, but seemed very unwilling to give up his good opinion of his own case: he told me of some concern and trouble he had been in about his soul in his younger years; but yet the case looked suspicious that he had got ease in a legal way, upon an outward form of religion.

At another time being at his house, and taking up a little book that lay by me on the table, which I found to be Mr Mather’s Dead Faith Anatomized,, and Self-Justiciary Convicted, he said to me, that was indeed as strange a book as ever be saw, and that according to that author it was a great thing indeed to have aright faith that was true and saving, another thing than it was generally supposed to be, or to this purpose.

He seemed to me at that time to be under more fears about his own case then I had observed in him before. Not long after this, as he was hearing a sermon one day, the word was applied with irresistible evidence and power to his heart, so that he saw himself as yet in a perishing undone case: whereupon the distress and exercise of his soul was so great that he fell off the seat on which he was sitting, and wept and cried very bitterly.

A little after this, he went to Philadelphia, at the time of the meeting of the Synod, in hopes that perhaps he might meet with some benefit to his soul by hearing the ministers preach there, or by conversing with some of them. He told me afterwards, that while he was there, and as he walked the streets, he was unspeakably distressed with the view of his miserable condition; so that he could hardly keep his distress from being publicly discerned upon him.

He seemed sometimes to be even in a manner afraid that the streets would open and swallow up such a wretched creature. He told me of his trouble, and his very sweet relief out of it, in a most moving manner, under a very fresh sense and impression of both; but the particulars of his relief I have quite forgot. He was afterwards chosen and set apart for a ruling elder in the congregation.

He died of an imposthume, and gradually wasted away for a long time before his death, and was for about two months entirely confined to his bed. He told me, that for some time before he was laid bedfast, he had been full of very distressing fears, and jealousies about his soul’s state, and was altogether unsatisfied about his interest in Christ; but that soon after he was confined to his bed, the Lord afforded him his comforting presence, cleared up his interest, and removed his fears.

After this he continued still clear and peaceful in his soul, and sweetly and wholly resigned to the Lord’s will until death. While he had strength to speak much he was free and forward to discourse of God and Divine things. One time as two other of our elders were with him, he exhorted them to continue steadfast and faithful to God’s truths and cause; for he said, if he had a thousand souls, he could freely venture them all upon the doctrines which had been taught them in this congregation.

One time when 1 took leave of him, he burst out into tears, saying, “I had been the messenger of the Lord of Hosts to him, whom the Lord had sent to call him out of the broad way of destruction. “ For some days before his decease he could speak very little, but to all appearance, with a great deal of serenity and sweetness of soul he fell asleep in Jesus.

Experiences of Children during the Revival

There have been very comfortable instances of little children among us. Two sisters, the one being about seven, the other about nine years of age, were hopefully converted that summer, when religion was so much revived here. I discoursed with them both very lately, and both from their own account, and the account of their parents, there appears to have been a lasting and thorough change wrought in them.

They speak of their soul-experiences with a very becoming gravity, and apparent impression of the things they speak of. The youngest was awakened by hearing the word preached; she told me she heard in sermons that except persons were convinced and converted they would surely go to hell, and she knew she was not converted.

This set her to praying with great earnestness, with tears and cries; yet her fears and distress continued for several days, till one time as she was praying, her heart, she said, was drawn out in great love to God; and as she thought of heaven and being with God, she was filled with sweetness and delight: I could not find by her that she had at that time any explicit particular thoughts about Christ as a Redeemer, but she said she knew then that Christ had died for sinners.

She told me, she often found such delight and love to God since as she did then, and at such times she was very willing to die that she might be with God: but she said, she wag sometimes afraid yet of going to hell. I asked her, “If she was troubled at any time when she was not afraid of going to hell? “ she said, “Yes: “ I asked her; What she was troubled for then? she said, “Because she had done ill to God; “ meaning that she had done evil and sin against God.

Sometime after she first found comfort, one night when her father and all the rest of the family, but her mother and herself, were gone to a private society, she said to her mother, “That the people were singing and praying where her father was gone, “ and desired her mother to do the same with her; and after they were gone to bed, “She desired her mother to sing some Psalms which she had by heart, for she said she did not want to go to sleep. “

Her sister was brought into trouble about her soul that same summer, by sickness; it continued with her some time after her recovery; until one day, coming home from meeting, as she heard some people speaking about Christ and heaven, her heart was enflamed with love to Christ. She says, that when she has Christ’s presence with her she does not know what to do to get away and be with God. “

Their parents told me that for a long time they seemed to be almost wholly taken up in religion that no weather through the extremity of winter would hinder them from going out daily to by-places for secret prayer; and if any thing came in the way that they could not get out for prayer at such times as they inclined and thought most proper, they would weep and cry.

Their parents say, they are very obedient children, and strict observers of the Sabbath. There are likewise other young ones in the place of whom I know nothing to the contrary, but that they continue hopeful and religious to this day.

This blessed shower of divine influences spread very much through this province that summer: and was likewise considerable in some other places bordering upon it.

Closing Remarks

The accounts of some ministers being something distinguished by their searching awakening doctrine, and solemn pathetic manner of address, and the news of the effects of their preaching upon their hearers, seemed in some measure to awaken people through the country to consider their careless and formal way of going on in religion; and very much excited their desires to hear those ministers.

There were several vacant congregations without any settled pastors, which earnestly begged for their visits; and several ministers who did not appear heartily to put their shoulder to help in carrying on the same work, yet then yielded to the pressing importunities of their people in inviting those brethren to preach in their pulpits: so that they were very much called abroad, and employed in incessant labours, and the Lord wrought with them mightily.

Very great assemblies would ordinarily meet to hear them, on any day of the week; and oftentimes a surprising power accompanying their preaching was visible among the multitudes of their hearers.

It was a very comfortable enlivening time to God’s people; and great numbers of secure careless professors, and many loose irreligious persons through the land, were deeply convinced of their miserable perishing estates; and there is abundant reason to believe and be satisfied, that many of them were in the issue savingly converted to God.

I myself have had occasion to converse with a great many up and down, who have given a most agreeable account of very precious and clear experiences of the grace of God. Several even in Baltimore, a county in the province of Maryland, who were brought up almost in a state of heathenism, without almost any knowledge of the true doctrines of Christianity, afford very satisfying evidences of being brought to a saving acquaintance with God in Christ Jesus.

Thus, Sir, I have endeavoured to give a brief account of the revival of religion among us in these parts; in which I have endeavoured, all along, to be conscientiously exact, in relating things according to the naked truth: knowing, that I must not speak wickedly, even for God; nor talk deceitfully for him. And upon the whole I must say, it is beyond all dispute with me, and I think it is beyond all reasonable contradiction, that God has carried on a great and glorious work of his grace among us.

SAMUEL BLAIR.

Having an opportunity of obtaining these attestations before sending my letter to you, I send them also along:— “New Londonderry, August 7, 1744: We, the under-subscribers, ruling elders in the congregation of New Londonderry, do give our testimony and attestation to the above account of the revival of religion in this congregation and other parts of this country, so far as the said account relates to things that were open to public observation, and such things as we have had an opportunity of being acquainted with.

Particularly, we testify that there has been a great and very general awakening among people, whereby they have been stirred up to an earnest uncommon concern and diligence about their eternal salvation, according to the above account of it: and, that many give very comfortable evidence by their knowledge, declaration of experience, and conscientious practice, of their being savingly changed and turned to God.

JAMES COCHRANE.

JOHN SMITH.

JOHN RAMSAY.

JOHN SIMSON.

JOHN LOVE.

WILLIAM BOYD.

The Log College

The Log College

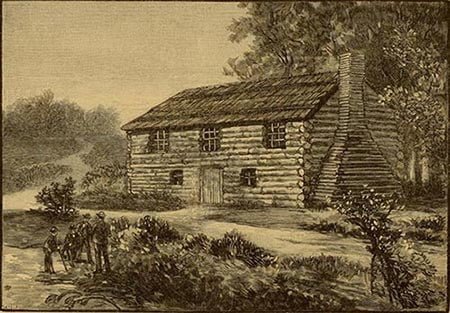

The Log College was the name of a school that William Tennent, an Irish-born, Edinburgh-educated Presbyterian minister, conducted at Neshaminy, Bucks County, Pennsylvania from 1726 until his death in 1745. Here, in a “log house, about twenty feet long and near as many broad, “ Tennent so filled his students with an evangelical zeal that a number of them, including his four sons and Samuel Blair, became greatly used in The Great Awakening.

For further research:

Samuel Blair Wikipedia