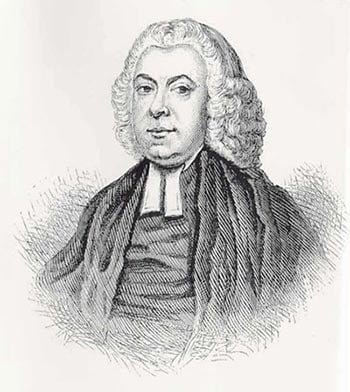

William Grimshaw 1708-1763

William Grimshaw

This sketch of William Grimshaw first appeared in ‘The Family Treasury’ along with eight other pen sketches of 18th century divines. They were published together as ‘Christian Leaders of the Last Century.’

Born at Brindle, 1708—Educated at Christ’s College, Cambridge—Ordained, 1731—Curate of Rochdale and Todmorden—Death of his Wife—Minister of Haworth, 1742—Description of Haworth—Style of his Ministry—His Manner of Life, Diligence, Charity, Love of Peace, Humility—His Ministerial Success.

The third spiritual hero of the last century whom I wish to introduce to my readers, is one who is very little known. The man I mean is William Grimshaw, Perpetual Curate of Haworth, in Yorkshire.

Thousands, I can well believe, are familiar with the history of Whitefield and Wesley, who have not so much as heard of Grimshaw’s name. Yet he was a mighty man of God, of whom the Church and the world were not worthy. If greatness is to be measured by usefulness to souls, I believe there were not in England a hundred years ago three greater men than William Grimshaw.

The reasons why this good man is so little known are soon explained.

For one thing, Grimshaw never withdrew from his position as a beneficed clergyman of the Church of England. He lived and died incumbent of a Yorkshire parochial district. He founded no new sect, and drew up no new articles of faith. He found as much liberty as he wanted within the pale of a beneficed clergyman’s position, and with that liberty he was content. Such a man, in the very nature of things, will rarely emerge from comparative obscurity. No zealous partisan will chronicle his actions and movements. No persecuted followers will publish accounts of his life and opinions. The man who remains in the ranks, or behind the intrenchments, will never be so conspicuous as he who carries on a guerilla warfare single-handed, or stands forth outside on the plain.

For another thing, Grimshaw never went to London, or opened his mouth so much as once in a London pulpit. He moved in a purely provincial orbit, in days when railways, telegraphs, and penny postage were not even dreamed of. Within that orbit, no doubt, he was a star of the first magnitude; but beyond it he was never heard or seen. We need not wonder that he was little known in his day and generation. The minister who never preaches in London, and writes nothing, must not be surprised if the world knows nothing of him. Like some of the judges of Israel, he may be great in his own district, but some of the tribes will scarcely be acquainted with his name.

After all, the being famous is a thing that depends greatly on position and opportunity. It is not enough to possess gifts and powers: there must also be the means of exhibiting them. For want of opportunity some of the greatest men perhaps are buried in obscurity. There may be great physicians who could never find a practice, great lawyers who could never get a brief, and great soldiers who never had a chance of distinguishing themselves. The main reason why the Church has done so little honour to Grimshaw’s name may be, that it had so little opportunity of knowing him.

William Grimshaw was born at Brindle, in Lancashire, on the 3rd of September 1708. Brindle is an agricultural parish, containing at present about thirteen hundred people, and lies not far from the three manufacturing towns of Preston, Chorley, and Blackburn. Nothing whatever is known of the rank and position of his parents. Who his mother was, whether he had any brothers and sisters, what was his father’s occupation and employment, are all points which are now veiled in complete obscurity. Beyond the fact that one of the churchwardens of Brindle in 1728 was a certain William Grimshaw, nothing has ever been ascertained.

About Grimshaw’s early life and education I can tell my readers almost nothing. That he went to the Grammar Schools of Blackburn and Hesketh, was admitted to Christ’s College, Cambridge, at the age of eighteen, and in due course of time took his degree as Bachelor of Arts, are the only facts that I can collect about the first twenty-one years of his life. But his character as a. boy and young man, and his conduct at school and college, are matters about which I cannot supply the slightest information, because none exists. There are, however, no grounds for supposing that he spent his time at all better than other young men of his day, or that he evinced any concern about religion.

In the year 1731 Grimshaw was ordained deacon, and entered holy orders as curate of Rochdale. He seems to have taken on him this solemn office without any spiritual feeling, and in utter ignorance of the duties of a minister of Christ’s gospel. Like too many young clergymen, he appears to have been ordained without knowing anything aright either about his own soul, or about the way to do good to the souls of others. In fact, in after-life he deeply lamented that he sought ordination from the lowest and most unworthy of motives—the desire to be in a respectable profession, and, if possible, to get a good living.

Grimshaw’s stay at Rochdale, for some reason which we cannot now explain, was a very short one. In September 1731, the very year that he was ordained, he became curate of Todmorden, and left Rochdale entirely. Todmorden lies in a romantic valley between Rochdale and Leeds, well known to all who-travel by the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway. Before the steam-engine was invented, it must have been a singularly beautiful place. Ecclesiastically, it is a chapelry in the patronage of the Vicar of Rochdale, and stands partly in the great parish of Rochdale and partly in the equally large parish of Halifax. Here Grimshaw continued for no less than eleven years.

The eleven years during which Grimshaw resided at Todmorden were, beyond doubt, the turning-point in his spiritual history. It is much to be regretted that we possess nothing but the most scanty information about this period of his life. Enough, however, exists to throw some light on the way through which he was led to become the man of God that he was in after-days.

It appears then, according to Middleton, one of his biographers, that about the year 1734, three years after he came to Todmorden, Grimshaw began for the first time to feel deep concern about his own soul, and the souls of his parishioners. A change came over his life and outward behaviour. He laid aside the diversions in which he had hitherto spent the greater part of his time—such as hunting, fishing, card-playing, revelling, and merry-making—and began to visit his people, and press on them the importance of religion, like one who really believed it. At the same time he commenced the practice of praying in secret four times a-day, a practice which there is reason to believe he never left off.

There is nothing to show that his views of Christianity at this period were any but the most dark and obscure. Of the distinctive doctrines of the gospel, of salvation by grace, justification by faith, free pardon through Christ’s blood, and the converting power of the Holy Ghost, he probably knew nothing at all. He had none but books of a very legal character, most of them given by Dr. Dunster, Vicar of Rochdale, when he was his curate. He had no friend to deal with him, as Peter did with Cornelius, or Aquila and Priscilla did with Apollos, and “show him the way of God more perfectly.” But he was honest in seeking light, and light came, though not immediately. He prayed much, like Saul in the house of Judas at Damascus, and after many days his prayer was heard. He used such means as he had, and in so using means God met him and helped him. He had a sincere desire to do God’s will, and the promise of the Lord Jesus was verified, “He shall know of the doctrine whether it be of God” (John 7:17).

The struggle between light and darkness in Grimshaw’s mind appears to have continued several years. Long as this delay may seem to us, we must not forget that he was entirely without help from man, and had to work out every spiritual problem unassisted and alone. But though the work within him went on slowly, it went on solidly and surely. The illness and death of his first wife, leaving him a desolate widower with two children, after four years of married life, appears to have been a powerful means of drawing him nearer to God. The perusal of two most valuable Puritan books, “Brooks’ Precious Remedies against Satan’s Devices,” and “Owen on Justification,” seems to have been extremely helpful and establishing to his soul. And the final result was, that after several years of severe conflict, Grimshaw no longer “walked in darkness, but had the full light of life” (John 8:12). The scales completely fell from his eyes. He saw and knew the whole truth, and the truth made him free. He left Todmorden a far wiser and happier man than he entered it. Hard as the schooling was, he there learned lessons which he never forgot to his life’s end. Few men, perhaps, have ever so thoroughly verified the truth of Luther’s saying, “Prayer and temptation, the Bible and meditation, make a true minister of the gospel.”

Grimshaw’s testimony to the power of the Scriptures at this crisis in his spiritual history, is very striking and instructive. Like many others, he found the Bible almost a new book to his mind. Up to this time he had known it only in the letter, but now he became acquainted with it in its spiritual power. He afterwards told a friend that “if God had drawn up his Bible to heaven, and sent him down another, it could not have been newer to him.” So true is it that when man becomes a new creature “old things pass away and all things become new.”

Grimshaw’s people at Todmorden soon found that a change had come over their minister’s mind. In the middle of his spiritual conflict, and before he had found peace, it is related that a poor woman came to him in great distress of soul, and asked him what she must do. He could only say, “I cannot tell what to say to you, Susan, for I am in the same state myself; but to despair of the mercy of God would be worse than all.” Another woman, named Mary Scholefield, of Calf Lees, had sought his advice in the beginning of his ministry, and got the following answer: “Put away these gloomy thoughts. Go into merry company. Divert yourself; and all will be well at last.” At a later period he went to her house and said, “O Mary, what a blind leader of the blind was I, when I came to take off thy burden by exhorting thee to live in pleasure, and to follow the vain amusements of the world!” Incidents like these, we may be sure, would soon be known throughout Todmorden. True conversion, like the presence of Christ, is a thing that cannot be hid.

It would indeed be interesting if we had any authentic records of Grimshaw’s history during these momentous eleven years at Todmorden. But God has thought fit to withhold them from us. It is certainly very curious that without the least concert with the other great evangelists who were his contemporaries, he should have arrived at the same doctrinal conclusions and taken up the same line of action. But it is an established fact, and well ascertained, that all the time he was at Todmorden he was an entire stranger to Whitefield and Wesley, and never read a line of their writings. It is no less curious to observe how God was pleased to wean him from the love of worldly things, by taking away his beloved wife, whose loss he seems to have felt most keenly. But the well-instructed Christian will see in all this part of his history the hand of perfect wisdom. The tools that the great Architect intends to use much, are often kept long in the fire, to temper them and fit them for work. The discipline that Grimshaw went through at Todmorden was doubtless very severe. But the lessons he learned under it could probably have been learned in no other school.

In the month of May 1742, Grimshaw was appointed minister of Haworth in Yorkshire, and remained there twenty-one years, until his death. How and by what interest he got the appointment, we do not know. At the present time, the patronage is in the hands of the Vicar of Bradford and certain trustees. It is not unlikely that his first wife’s family had something to do with it. Haworth is a chapelry in the parish of Bradford, and about four miles from the town of Keighley. It stands in a cold, desolate, bleak moorland country, on the hills which divide Yorkshire from Lancashire, and, running down from the Lake district to the peak of Derbyshire, form the “backbone” of England. None but those who have travelled from Manchester to Leeds by the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway, or from Manchester to Huddersfield by the London and North-Western, or from Manchester to Sheffield by the Great Northern line, can have any adequate idea of the rugged, weather-beaten, mountainous character of this district. Its valleys are beautiful, highly cultivated, and teeming with life and manufacturing activity. But the upper parts of the country are often as wild, and steep, and uncultivated, and unapproachable, as a Highland moor. At the top of one of the roughest parts of the mountain district lies the village of Haworth, the principal scene of Grimshaw’s ministerial labour.

Haworth a hundred years ago was perhaps as rough and uncivilized a place as a minister could go to. Even Doomsday-Book specially describes it as desolate and waste. It is a long narrow village, built of brown stone, approached by a steep ascent from Keighley or Hebden bridge. The street is so steep that one can understand it must have been only recently that wheeled carriages went there. Indeed, there is a legend that when the first carriage came to Haworth the villagers brought out hay to feed it, under the idea that it was an animal! Such was the parish in which Grimshaw set up the standard of the cross. A less promising field can hardly be imagined.

Grimshaw began his work at Haworth after a manner very different from his beginning at Todmorden. He commenced preaching to his wild and rough parishioners the gospel of Christ in the plainest and most familiar manner, and followed up his preaching by house to house visitation. His preaching was not confined to the walls of the church. Wherever he could get people together, whether in a room, a barn, a field, a quarry, or by the roadside, he was ready to preach. His visiting was not a mere going from family to family to gossip about temporal matters, sickness, and children. Wherever he went he took his Master with him, and spoke plainly to people about their souls. In this kind of work his whole life was spent at Haworth. Preaching publicly and privately repentance toward God, and faith toward our Lord Jesus Christ, after the manner” of St. Paul, was his one employment throughout the whole twenty-one years of his ministry. He himself describes his mode of action in the following letter:

“The method which I, the least and most unworthy of my Lord’s ministers, take in my parish, is this: I preach the gospel —glad tidings of salvation to penitent sinners through faith in Christ’s blood only—twice every Sunday the year round, save when I expound the Church Catechism and thirty-nine articles, or read the Homilies, which in substance I think my duty to do in some part of the year annually, on the Lord’s day mornings. I have found this practice, I bless God, of inexpressible benefit to my congregation, which consists, especially in the summer season, of perhaps ten or twelve hundred souls, or, as some think, many more. We have also prayer, and a Chapter expounded every Lord’s Day evening. I visit my parish in twelve several places monthly, convening six, eight, or ten families in each place, allowing any people of the neighbouring parishes that please to attend the exhortation. This I call my monthly visitation. I am now entering into the fifth year of it, and wonderfully has the Lord blessed it. The only thing more are our funeral expositions and exhortations, and visiting our societies in one or other of the three last days of the month. This I purpose, through the grace of God, to make my constant business in my parish so long as I live.”

In carrying on this kind of work, Grimshaw gladly availed himself of every help that he could obtain from likeminded men. He became acquainted with John Nelson, the famous Yorkshire stone-mason, one of the most remarkable lay-preachers whom Wesley sent forth, and frequently received him at Haworth. He welcomed those few clergymen who were of one heart with himself, and seized every opportunity of getting them to preach to his people. Whitefield, the two Wesleys, Romaine, and Venn, were among those whom he was only too glad to place in his pulpit. On such occasions it was no uncommon thing to leave the church and—preach in the churchyard, in order to meet the convenience of the crowds who came together. When the Lord’s Supper was administered at such seasons, it was sometimes necessary for the first congregation of communicants to retire from the church and give way to others, until all had partaken of the ordinance. In one instance, when Whitefield was present, the numbers who came to the Lord’s Table were so great that no less than thirty-five bottles of wine were used!

The effect produced by this new and fervent style of ministration, as might well be expected, was very great indeed. An interest about religion was aroused throughout the whole district round Haworth, and multitudes began to think who had never thought before. Grimshaw himself says, in a letter to Dr. Gillies, author of the “Historical Collections:” “Souls were affected by the word, brought to see their lost estate by nature, and to experience peace through faith in the blood of Jesus. My church began to be crowded, insomuch that many were obliged to stand out of doors. Here, as in many places, it was amazing to see and hear what weeping, roaring, and agony, many people were seized with, at the apprehension of their sinful state and wrath of God. After a season I joined people, such as were truly seeking, or had found the Lord, in society, for meetings and exercises. These meetings are held once a week, about two hours, and are called classes, consisting of about ten or twelve members each. We have much of the Lord’s presence among them, and greatly in consequence must such meetings conduce to Christian edification.”

The style of preaching which Grimshaw adopted was peculiarly well suited to the rough and uneducated population with which he had to do. He was eminently a plain preacher. His first aim undoubtedly was to preach the whole truth as it is in Jesus; his second was to preach so as to be understood. To accomplish this end he was willing to make many sacrifices, to crucify his natural taste as an educated clergyman who had been at Cambridge, and to be thought a fool by intellectual men. But he cared nothing so long as he could succeed in reaching the hearts and consciences of his hearers. John Newton, who knew him well, has left some remarks on this characteristic of Grimshaw’s preaching which are well worth reading. He says: “The desire of usefulness to persons of the weakest capacity, or most destitute of the advantages of education, influenced his phraseology in preaching. Though his abilities as a speaker, and his fund of general knowledge, rendered him very competent to stand before great men, yet, as his stated hearers were chiefly of the poorer and more unlettered classes, he condescended to accommodate himself, in the most familiar manner, to their ideas, and to their modes of expression. Like the apostles, he disdained that elegance and excellence of speech which is admired by those who seek entertainment perhaps not less than instruction from the pulpit. He rather chose to deliver his sentiments in what he used to term ‘market language.’ And though the warmth of his heart and the rapidity of his imagination might sometimes lead him to clothe his thoughts in words which even a candid critic could not justify, yet the general effect of his plain manner was striking and impressive, suited to make the dullest understand, and to fix for a time the attention of the most careless. Frequently a sentence which a delicate hearer might judge quaint or vulgar, conveyed an important truth to the ear, and fixed it on the memory for years after the rest of the sermon and the general subject were forgotten. Judicious hearers could easily excuse some escapes of this kind, and allow that, though he had a singular felicity in bringing down the great truths of the gospel to a level with the meanest capacity, he did not degrade them. The solemnity of his manner, the energy with which he spoke, the spirit of love which beamed in his eyes and breathed through his addresses, were convincing proofs that he did not trifle with his people. I may give my judgment on this point, something in his own way, by quoting a plain and homely proverb which says, that is the best cat which catches the most mice.’ His improprieties, if he was justly chargeable with any, are very easily avoided; but few ministers have had equal success. But if his language was more especially suited to the taste of his unpolished rustic hearers, his subject-matter was calculated to affect the hearts of all, whether high or low, rich or poor, learned or ignorant; and they who refused to believe were often compelled to tremble.”

The manner in which he conducted public worship at Haworth seems to have been as remarkable as his preaching. There was a life, and fire, and reality, and earnestness about it, which made it seem a totally different thing from what it was in other churches. The Prayer-Book seemed like a new book; and the reading-desk was almost as arresting to the congregation as the pulpit. Middleton, in his life of him, says: “In performance of divine service, and especially at the communion, he was at times like a man with his feet on earth and his soul in heaven. In prayer, before sermon, he would indeed take hold (as he used to say) of the very horns of the altar,’ which, he added, he could not, he would not, let go till God had given the blessing.’ And his fervency often was such, and attended with such heartfelt and melting expressions, that scarcely a dry eye was to be seen in his numerous congregation.”

The life which Grimshaw lived appears, by the testimony of all his contemporaries, to have been as remarkable as his preaching. In the highest sense he seems to have adorned the doctrine of the gospel, and to have made it beautiful in the eyes of all around him. He was not like some of whom the bitter remark has been made, that when they are in the pulpit it is a pity they ever get out of it, and when out of it, a pity that they should ever get in. The sane Christ that he preached in the pulpit was the Christ that he endeavoured to follow in his daily life.

He was a man of rare diligence and self-denial. None ever worked harder than he did in his calling, and few worked so hard. He seldom preached less than twenty, and often nearly thirty times in a week. In doing this he would constantly travel scores of miles, content with the humblest fare and the roughest accommodation.

He was a man of rare charity and brotherly love. He loved all who loved Christ, by whatever name they might be called, and he was kind to everyone in temporal as well as spiritual things. “In fact,” says Middleton, “his charity knew no bound but his circumstances. As his grace and faithfulness rendered him useful to all, so his benevolent liberality particularly endeared him to the poor. He frequently used to say, ‘If I shall die today I have not a penny to leave behind me.’ And yet he did not quit the world in debt, for he had prudence as well as grace.”

He was preeminently a peacemaker. “The animosities and differences of men,” says Middleton, “afforded his affectionate spirit nothing but pain. No labour was too great or too long if their reconciliation might be his reward. When he has met with cases of uncommon perseverance or obduracy, he has been known to fall on his knees before them, beseeching them, for Christ’s sake, to love one another, and offering to let them tread on his neck if they would only be at peace among themselves.”

He was, above all, a man of rare humility. Few gifted men, perhaps, ever thought so meanly of themselves, or were so truly ready in honour to prefer others. “What have we to boast of?” he said. “What have we that we have not received? Freely by grace we are saved. When I die I shall then have my greatest grief and my greatest joy,—my greatest grief that I have done so little for Jesus, and my greatest joy that Jesus has done so much for me. My last words shall be, “ Here goes an unprofitable servant! “

That such a man as Grimshaw should soon obtain immense influence in Haworth is nothing more than we might expect. Preaching as he did and living as he did, we can well understand that he produced a mighty impression on his wild parishioners. Sin was checked, Sabbath-breaking became unfashionable, immorality was greatly restrained. Like John the Baptist in the wilderness, he shook the little corner of Yorkshire where he was placed, and stirred men’s minds to the very bottom. Hundreds learned to fear hell who did not really love heaven. Scores were restrained from sin though they were not converted to God.

But this was not all. There can be no doubt that Grimshaw was the means of true conversion to many souls. Year after year the Holy Ghost applied his sermons to the hearts and consciences of not a few of his hearers, and added to the true Church of Christ such as should be saved. In one single year, after burying eighteen persons, he said that “he had great reason to believe that sixteen of them were entered into the kingdom of God.”

“Not long before his death,” says one of his biographers, “he stood with the Revelation John Newton upon a hill near Haworth surveying the romantic prospect. He then said that at the time he first came into that part of the country he might have gone half a day’s journey on horseback toward the east, west, north, and south, without meeting one truly serious person, or even hearing of one. But now, through the blessing of God upon his labours, he could tell of several hundreds of persons who attended his ministry, and were devout communicants with him at the Lord’s Table; and of nearly all the last-named he could say that he was as well acquainted with their several temptations, trials, and mercies, both personal and domestic, as if he had lived in their families.”

The extra-parochial labours which-Grimshaw undertook, and the persecutions which they entailed upon him, his early death, and some account of his few literary remains, are subjects of so much interest that I must defer them to another Chapter.

Chapter 2

Extra-Parochial Labour in Yorkshire, Lancashire, and Cheshire—The Nature of this Labour Explained and Defended—Persecution at Colne—The Archbishop of York’s Visit to Haworth—His Love to the Articles and Homilies—His Last Illness, Dying Sayings, Death, and Funeral.

THE religious condition of England a hundred years ago was so deplorably bad, that a man like Grimshaw was not likely to confine his labours to his own parish. Led by the force of circumstances, he soon began to preach outside his parochial boundaries, and finally “did the work of an evangelist” throughout the whole region within fifty miles of Haworth.

The circumstances which led Grimshaw into this course of action are soon explained. Hundreds of his regular hearers at Haworth were not his parishioners, and came together from distant places. Once taught of God to know the value of the gospel, they went out of their own parishes to get the spiritual food which they could not find at home. It was only natural that these people should feel for their families and neighbours, and desire that they might hear what had done good to themselves. They asked Grimshaw to come and preach at their houses, and represented to him the ignorance and spiritual destitution of all around their own homes. They entreated him to come and tell their friends and relatives the same things he was every week telling his congregation at Haworth. They told him that souls were perishing for lack of knowledge, unshepherded, uncared for, and untaught, and promised him a hearty welcome if he would “come over” his parish boundaries and “help” them. Appeals like these, we can well believe, were not made in vain. In a short time these extra-parochial labours became a regular and systematic business. The voice of the incumbent of Haworth was soon heard in many other places beside his parish-church, and for many years he was known throughout Yorkshire, Lancashire, Cheshire, and North Derbyshire, as the apostle and preacher of the district.

It would be interesting to name all the places which Grimshaw was in the habit of visiting as an evangelist, but it is impossible to do so. No accurate record remains of the extent of his labours, and he left no journal behind him. It is known, however, that in Yorkshire he used to preach at Leeds, Halifax, Bradford, Manningham, Todmorden, Birstal, Keighley, Otley, Bingley, Bramley, Heptonstall, Luddenden, and Osmotherley. In Lancashire, he used to visit Manchester, Bolton, Rochdale, Colne, Padiham, Holme, Bacop, and Rossendale. In Cheshire, we find him at Stockport, Tarvin, and Rostherne; and in Derbyshire at Mellor. These places are probably not a tenth part of those he visited, but they are places specially mentioned by his biographers.

In all these places the people who valued such preaching as Grimshaw’s were banded together in societies, and generally under the direction of one man. The incumbent of a large parish like Haworth, of course, could only leave his own work for a short time, and visit distant preaching-stations at long intervals. Between his visits, the societies were necessarily left very much to themselves and their local leaders. Conference with these leaders, receiving reports from them of the spiritual condition of the societies, and arranging with them for breaking up new ground as well as keeping old ground in cultivation, made no small part of Grimshaw’s extra-parochial work. To these leaders of societies was left the provision of rooms, or barns, or convenient fields for preaching, and the collection of money to defray expenses. Thus, when the incumbent of Haworth, or some like-minded friend, paid his periodical visit, he had nothing to do but to preach.

The managers or leaders of these societies, scattered about Yorkshire, Lancashire, and Cheshire, were seldom above the middle class, and frequently no more than intelligent small farmers. There is no evidence that Grimshaw’s ministry ever had much effect upon the upper ranks, or indeed was ever brought to bear upon them. But none but an ignorant man will ever think the worse of it on that account. To get hold of the lower middle and lower classes of society, and enlist them in the service of Christ, is at this day one of the greatest problems the Churches have to solve. If Grimshaw succeeded in doing this, it is enough to prove that he was no common man. A church is never in so healthy a state as it is when the common people hear gladly.

Let the following extract from Hardy’s “Life of Grimshaw” supply an instance of the sort of people that Grimshaw got hold of in his itinerant labours outside his own parish:— “At Booth Bank, in the parish of Rostherne, Cheshire, Grimshaw’s services used to be held in the house of John and Alice Cross. Alice was a woman of great spirit and intrepidity, and a heroine in Christ’s service. Her husband was a quiet sober man, but for some time after her conversion he remained in his old ways. When going out to worship, with her straw hat in one hand and the door-latch in the other, she would say to him, John Cross, wilt thou go to heaven with me ‘I If thou wilt not, I am determined not to go to hell with thee!’ John yielded at last; a pulpit was fixed in the largest room of their house at Rostherne, and the messengers of God were made welcome to their fare and farm. When beggars came to the door she told them of the riches that are in Christ Jesus, and, kneeling by their side, commended them to the grace of God, and then sent them away, grateful for her charity, and impressed by her earnestness in seeking their souls’ good. Nor were the more honourable of the land beyond the reach of her reproofs. On one occasion she stopped the Cheshire hunt, when passing her house, and addressed the horsemen, especially Lord Stamford and Sir Harry Main-waring, who listened to her warning and rode on. When the expected preacher did not come, though the pulpit was not occupied, the congregation did not go empty away. Alice Cross herself, in her simple and earnest way, dealt out the bread of life.” Such were the kind of households that Grimshaw used to make centres of operation in his extra-parochial evangelism. Such were the kind of people who valued his labours, welcomed his visits, and proved the value of his preaching, in the district within fifty miles of Haworth.

No doubt these extra-parochial labours of Grimshaw will appear wrong to many in the present day. Many are such excessive lovers of parochial order that they feel scandalized at the idea of an incumbent preaching in other men’s parishes. Such people would do well to remember the condition of England in Grimshaw’s times. There were scores and hundreds of parishes all over the north of England in which there was no resident clergyman; and the services of the Church, even when performed, were cold, brief, and utterly unprofitable. To tell us that Grimshaw ought to have left the inhabitants of these parishes to perish in ignorance rather than commit a breach of parochial order, is simply ridiculous. Men might as well tell us that we must not knock at a person’s door and awaken him, when his house is on fire, because we have not the honour of his acquaintance! The parochial system of the Church of England was designed for the good of men’s souls. It was never intended to ruin souls by cutting them off from the sound of the gospel.

The thing that is really wonderful, in the history of Grimshaw’s extra-parochial labours, is the noninterference of ecclesiastical authorities. How the incumbent of Haworth can have gone on for fifteen or twenty years preaching all over Lancashire, Yorkshire, and Cheshire, without being stopped by bishops and archdeacons, is very hard to understand! Let us charitably hope that many felt in their secret hearts that some such evangelism as his was absolutely needed. The enormous size of such parishes as Bradford and Halifax in Yorkshire—as Whalley, Rochdale, and Prestwich, in Lancashire—as Stockport, Astbury, and Prestbury, in Cheshire, made it utterly. impossible for the clergymen of the mother-churches to provide means of grace for their parishioners. We may well believe, that to arrest such labours as Grimshaw’s in these unwieldy parishes would have been so unwise, that even bishops and archdeacons of the last century shrank from attempting it. Be the cause what it may, it is a most curious fact that Grimshaw was never entirely stopped in his extra-parochial ministry. The hand of the Lord was with him, and he carried on his itinerant work, as well as his regular services at Haworth, up to his death.

But though Grimshaw was never actually stopped, we must not suppose that he escaped persecution. The prince of this world will never willingly part with any of his subjects. He will stir up opposition against anyone who tries to pull down his kingdom. The incumbent of Haworth was often obliged to face abuse and personal violence of a kind that we can hardly imagine in the present day. “Mad Grimshaw” was the name given to him by many throughout the district in which he laboured. None opposed him more than some of the clergy. With the true dog-in-the-manger spirit, they neither did good themselves nor liked anyone else to do it for them.

The most violent of Grimshaw’s opponents was the Revelation George White, perpetual curate of Colne and Marsden, in Lancashire. This worthy commenced his attack by publishing a sermon against the Methodists, preached at his two churches in August 1748. In this sermon he charged Grimshaw and all his fellow-labourers with being “authors of confusion; open destroyers of the public peace; flying in the face of the very Church they craftily pretend to follow; occasioning many bold insurrections, which threaten our spiritual government; schismatical rebels against the best of Churches; authors of a further breach in our unhappy divisions; contemners of the great command, Six days shalt thou labour;’ definers of all laws, civil and ecclesiastical; professed disrespecters of learning and education; causing a visible ruin of trade and manufactures; and, in short, promoters of a shameful progress of enthusiasm and confusion not to be paralleled in any other Christian dominion.”

Not content with preaching this stuff and nonsense, White proceeded to stir up a mob to stop the preaching of Grimshaw and his companions by force and violence. He actually issued a proclamation, in order to collect a mob, in the following words: “Notice is hereby given, that if any men be mindful to enlist into His Majesty’s service, under the command of the Revelation George White, commander-in-chief; and John Banister, lieutenant-general of His Majesty’s forces, for the defence of the Church of England, and the support of the manufactures in and about Caine, both which are now in danger, let them now repair to the cross, when each man shall have a pint of ale for advance, and other proper encouragements.”

The consequence of this outrageous proclamation was just what might have been expected. “Lewd fellows of the baser sort” are always ready to make a riot against religion, as they were in the days of St. Paul. When Grimshaw and John Wesley went to Colne to preach, on the 24th of August 1748, they were attacked by an overwhelming mob of drunken people armed with clubs, and dragged before White like thieves and malefactors. After a vain endeavour to extort a promise from them that they would desist from coming to preach at Colne, they were allowed to leave the house. As soon as they got outside, “the mob closed in upon them, and tossed them about with great violence, throwing Grimshaw down, and covering both of them with mire, there being no one to come to their rescue. The people who had assembled to hear the word of God were treated with even greater cruelty. They had to run for their lives, amidst showers of dirt and stones, and no regard was paid to either sex or age. Some were trampled in the mire; others dragged by the hair; and many were unmercifully beaten with clubs. One was forced to leap from a rock, ten or twelve feet high, into the river, to prevent being thrown in headlong. When he crawled out, wet and bruised, they swore they would throw him in again, and were with difficulty prevented from executing their threat. White, well-pleased, was watching his mad followers all this time without a word to stay them.”

None of these things moved the lion-hearted incumbent of Haworth. Not long afterwards he went to Colne again, and was again shamefully treated—pelted with mud and dirt, and dragged violently along the road. In the following year, 1749, he published a long reply to White’s sermon, extending to eighty-six pages, in which he powerfully and triumphantly refuted White’s charges.

Persecution of this rough kind was not the only hard measure that Grimshaw had to undergo in consequence of his extra-parochial evangelism. He was more than once called to account for his conduct by the Archbishop of York, and seems to have escaped suspension or deprivation in a most marvellous manner.

On one occasion “a charge was preferred against him for having preached in a licensed meeting-house at Leeds. Had proof been forthcoming to substantiate the charge, he would have been dismissed from his cure for irregularity. Though no act of delinquency was proved, he was obliged to promise the archbishop that he would not preach in any place that had been licensed for the worship of dissenters; while he repeated his determination to continue preaching abroad so long as there were souls for whom no one seemed to care. On another occasion, when accused of preaching out of his own parish, he was asked by the archbishop, How many communicants had you when you first came to Haworth? He answered, ‘Twelve, my lord.’ ‘How many have you now?’ was the next question. The reply was, ‘In the winter, from three to four hundred; and in the summer, near twelve hundred.’ On hearing this the archbishop expressed his approbation, and said, We cannot find fault with Mr. Grimshaw when he is instrumental in bringing so many persons to the Lord’s Table.”

On another occasion, “when complaint was made to the archbishop of his ramblings and intrusions into other men’s folds, the archbishop announced his intention to hold a confirmation-service in, Mr. Grimshaw’s church, and to have an interview with him on the occasion. On the day appointed they met in Haworth vestry, and while the clergy and laity were assembling in great numbers, the following conversation took place: I have heard,’ said the archbishop, many extraordinary reports respecting your conduct, Mr. Grimshaw. It has been stated to me that you not only preach in private houses in your parish, but also travel up and down, and preach where you have a mind, without consulting your diocesan or the clergy into whose parishes you obtrude your labours; and that your discourses are very loose; that, in fact, you can and do preach about anything. That I may be able to judge for myself, both of your doctrine and manner of stating it, I give you notice that I shall expect you to preach before me and the clergy present in two hours hence, and from the text which I am about to name.’ After repeating the text, the archbishop added: ‘Sir, you may now retire, and make what preparation you can while I confirm the young people.’ —’My lord,’ said Grimshaw, looking out of the vestry-door into the church, see what multitudes of people are here! Why should the order of the service be reversed, and the congregation kept out of the sermon for two hours? ‘Send a clergyman to read prayers, and I will begin immediately.’ After prayers Mr. Grimshaw ascended the pulpit, and began an extempore prayer for the archbishop, the people, and the young persons about to be confirmed, and wrestled with God for his assistance and blessing, until the congregation, the clergy, and the archbishop himself, were moved to tears. After the service was over, the clergy gathered round the archbishop to ascertain what proceedings he intended to adopt in order to restrain the preacher from such rash and extemporaneous expositions of God’s Word. To their surprise the archbishop, taking Mr. Grimshaw by the hand, said with a tremulous voice, I would to God that all the clergy in my diocese were like this good man Mr. Grimshaw afterwards observed to a party of friends who came to take tea with him that evening, I did expect to be turned out of my parish on this occasion; but if I had been I would have joined my friend John Wesley, taken my saddle-bags and gone to one of his poorest circuits.”

It is impossible to turn from this part of Grimshaw’s history without feelings of righteous indignation. There is something revolting in the idea of a holy and zealous minister of the Church of England being persecuted for overstepping the bounds of ecclesiastical etiquette, while hundreds of clergymen were let alone and undisturbed whose lives and doctrine were beneath contempt. All over England country livings were often filled by hunting, shooting, gambling, drinking, card-playing, swearing, ignorant clergymen, who cared neither for law nor gospel, and utterly neglected their parishes. When they did preach, they either preached to empty benches, or else “the hungry sheep looked up and were not fed.” And yet these men lived under their own vines and fig-trees enjoying great quietness, untouched by bishops, eating the fat of the land, and calling themselves the true supporters of the Church! But the moment a man rose up like Grimshaw, who gloried in the Articles, Liturgy, and Homilies, and preached the Gospel, he was treated like a felon and malefactor, and his name cast out as evil! Truly God’s patience with the Church of England a hundred years ago was something marvellous. Marvellous that he did not remove our candlestick altogether! Marvellous that he granted her such a revival, and raised up so many burning and shining lights amongst her ministers!

To talk of Grimshaw being no Churchman and being an enemy to the Church of England, is preposterous and absurd. If attachment to the standards and formularies of his own communion is a mark of Churchmanship, he was a Churchman in the truest sense. No doubt he loved all who loved Jesus Christ in sincerity. No doubt he made nothing of parochial boundaries when souls were perishing, and other clergymen neglected their duties. But to the day of his death he was a steady adherent of the Church in which he had been ordained, used her services devoutly and regularly, and did more for her real interests than any clergyman in the north of England. One of his biographers specially mentions “that he greatly admired the Homilies, and regarded their disuse, and neglect of the Thirty-nine Articles, as the chief occasion of all the mischief to the Church, believing it probable that if they had been constantly read Methodism would never have appeared.” He said once, that an old clergyman of his acquaintance, being asked by his curate if he might read the Homilies in the pulpit, answered “No! For if you should do so, the whole congregation would turn Methodists.” On another occasion he wrote to Charles Wesley the following remarkable words: “I see nothing so materially amiss in the liturgy, or the Church constitution, as to disturb my conscience or justify my separation. No: where shall I go to mend myself? I believe the Church of England to be the soundest, purest, and most apostolical national Christian Church in the world. Therefore I can in good conscience (as I am determined, God willing, to do) live and die in her.” Yet this is the man who, some dare to tell us, was no Churchman!

Grimshaw’s holy and useful career was brought to an end on the 7th of April 1763. He died in his own house at Haworth of a putrid fever, in the fifty-fifth year of his age and the twenty-first of his ministry at Haworth. The fever of which he died had been raging in his parish from the beginning of the year, and had proved fatal to many of the inhabitants. “On its first breaking out,” says Hardy, “he had a presentiment that it would prove fatal to some member of his family, and had exhorted all to be ready.” When visiting a parishioner he caught the prevailing epidemic, and at once predicted that he would not recover.

To the physician who attended him “he expressed in strong terms the humiliating feelings he had on a retrospect of his whole life, and how disproportionate, defective, and defiled his best services had been, compared with the obligation under which he felt himself, and the importance of the cause in which he had been engaged; and that he hoped, if the Lord should prolong his days and raise him up, to be much more active and diligent.”

To his friend and brother in the gospel, the Revelation Mr. Ingham, he said; “My last enemy is come! The signs of death are upon me. But I am not afraid. No! no! Blessed be God, my hope is sure, and I am in his hands.” Afterwards, when Mr. Ingham prayed for the lengthening of his life, that he might yet be useful to Christ’s cause, he said, “Alas! what have my wretched services been I have now need to cry, at the end of my unprofitable course, God be merciful to me a sinner!” At another time, laying his hand on his heart, he said, “I am quite exhausted; but I shall soon be at home—for ever with the Lord—a poor miserable sinner redeemed by his blood.”

His valued fellow-labourer, the Revelation Henry Venn, then vicar of Huddersfield, came over to see him from Huddersfield, and asked him how he felt. To him he replied, “Never had I such a visit from God since I first knew him. I am as happy as I can be on earth, and as sure of glory as if I were in it.” After this, “finding that his disease was peculiarly infectious and dangerous, he requested his friends to visit him as little as possible. But his peace and hope are reported to have continued unshaken to the end. As he lived so he died, rejoicing in Christ Jesus, and putting no confidence in the flesh.”

He was buried, by his own desire, by the side of his first wife in the chancel of Luddenden Church, in the valley of the Calder, not far from Haworth. Like Joseph, “he gave commandment concerning his bones.” He had drawn up full and particular directions about his funeral long before he was taken ill, and these directions were carefully followed. The number of attendants was to be twenty, “religious or relative friends, or both.” He would have only a plain, poor man’s burial suit, and a plain, poor man’s coffin of elm boards, with the words on the cover, “To me to live is Christ, and to die is gain.” All the way to the church suitable verses were to be sung, in various selected metres and tunes, out of the 23 rd, 39th, and 91 st Psalms, and also suitable hymns. One of the attendants, at least, was to be a Methodist preacher, and he was to preach a funeral sermon from the text on his coffin (Philippians 1:21). The Methodist preacher selected for the occasion was his old friend and fellow-labourer, Henry Venn. The church at Luddenden was too small to contain the immense congregation which assembled, and the preacher had to take his position in the grave-yard. “Tradition reports,” says Hardy, “that Venn’s voice rose like the swell of a full-toned bell as he told forth the virtues of his departed friend, and exhorted the people to follow him as he had followed Christ.” Never, indeed, had any man a more honourable burial. Like Stephen, “devout men carried him to his grave, and made great lamentation over him.” He had, as Venn well remarks, “what is more ennobling than all the pomp of solemn dirges, or of a royal funeral. He was followed to the tomb by a great multitude, who beheld his corpse with affectionate sighs and many tears, and who cannot still hear his much-loved name without weeping for the guide of their souls.”

Grimshaw was twice married, and twice left a widower. His first wife was Sarah, daughter of John Lockwood of Ewood Hall. She had been twice married before, first to William Sutcliffe of Scaitcliffe Hall, and secondly to John Ramsden, both of whom died without children. He was evidently greatly attached to his first wife, and her death, on the 1 st of November 1739, made a deep impression on him. His second wife was Elizabeth, daughter of Henry Cockcroft of Mayroyd, near Hebden Bridge. I can find no record of the date of her death.

Grimshaw had only two children, both by his first wife, a son and a daughter. His daughter died when only twelve years old, when at school at Kingswood, near Bristol. Charles Wesley says that “she departed in the Lord.” His son survived his father only three years, and died childless. During his father’s lifetime he had been careless and intemperate, and the cause of great grief. When he visited him on his deathbed, Grimshaw told him to take care what he did, as he was not fit to die. To him also he used the remarkable words that “his body felt like a boiling vessel, but his soul was as happy as it could be made by God.” John Grimshaw died at Ewood on the 17th May 1766, and by God’s great mercy there was hope in his death. His father’s dying words perhaps sunk into his heart, and at any rate his father’s many prayers for him were heard. After his father’s death, he used to ride a horse which formerly belonged to him, and one day meeting an inhabitant of Haworth, the man remarked, “I see you are riding the old parson’s horse.”— “Yes,” was the reply; “once he carried a great saint, and now he carries a great sinner.” Long before his death young Grimshaw had given clear evidence of repentance unto salvation, and found pardon and peace in Christ; and a little time before he died, he was heard to exclaim, “What will my old father say when he sees I have got to heaven?”

Chapter 3

Literary Remains—Covenant and Summary of Belief—Letter to Christians in London—Anecdotes and Traditions—Influence in his Parish—Haworth Races Stopped—Mode of Discovering False Professors—Peculiarities in his Conduct of Divine Service—Testimony of Romaine, Venn, and Newton.

In order to form a correct estimate of a great man’s character, there are two sources of information to which we should always turn, if possible, in addition to the events of his life. The literary remains he leaves behind him form one of these sources; the anecdotes handed down about him by contemporaries form another. From both these sources I will endeavour to supply the reader of these pages with some further information about William Grimshaw.

The literary remains of a man like Grimshaw are necessarily few and scanty. It could hardly be otherwise. A clergyman who was constantly preaching twenty or thirty times a week, and carrying on a system of aggressive evangelism all over Yorkshire, Lancashire, and Cheshire, was not likely to have much time for writing. In fact, his “Reply to White,” already referred to, is the only formal publication that he ever put forth. He says himself in the Reply, “I have as little leisure for writing as for anything I do.” There are, however, a few valuable relics of his thoughts still extant, which are useful, as indicating his turn of mind, and will probably be thought interesting by all Christian readers.

His covenant with God, given at length by Hardy, is a very striking and interesting document, though too long for the pages of a memoir like this. The following disconnected extracts will give some idea of it:—

“Eternal and unchangeable Jehovah! thou great Creator of heaven and earth, and adorable Lord of angels and men! I desire with the deepest humiliation and abasement of soul to fall down at this time in thine awful presence, and earnestly pray that thou wilt penetrate my heart with a suitable sense of thine unutterable and inconceivable glories.”

“I know that through Jesus, the Son of thy love, thou condescendest to Visit sinful mortals, and to allow their approach to thee and this covenant intercourse with thee. Nay, I know that the scheme and plan are entirely thine own, and that thou hast graciously sent to propose it unto me, as none untaught by thee could have been able to join it, or inclined to embrace it, even when actually proposed.”

“To thee, therefore, do I now come, invited by thy love, and trusting his righteousness alone, laying myself at thy feet with shame and confusion of face, and smiting on my breast, saying with the publican, God be merciful to me a sinner! I acknowledge, O Lord, that I have been a great transgressor. My sins have reached unto heaven, and mine iniquities have been lifted up unto the skies. My base corruptions and lusts have numberless ways wrought to bring forth fruit unto death, and if thou wert extreme to mark what I have done amiss, I could never abide it. But thou hast graciously called me to return unto thee, though I am a prodigal son and a backsliding child. Behold, therefore, I solemnly come before thee. O my Lord, I am convinced of my sin and folly. Thou knowest, O Lord, I solemnly covenanted with thee in the year 1738. And now, once more and for ever, I most solemnly give up, devote, and resign all I am, spirit, soul, and body to thee, and to thy pleasure and commands in Christ Jesus my Saviour, this 4th of December 1752; sensible of my vileness and unworthiness, but yet sensible that I am thy pardoned, justified, and regenerated child in the spirit and blood of my dear and precious Saviour, Jesus Christ, by clear experience.”

“Glory be to thee, O my Triune God! Permit me to repeat and renew ay covenant with thee. I desire and resolve to be wholly and for ever thine. Blessed God, I most solemnly surrender myself unto thee. Hear, O heaven, and give ear, O earth! I avouch this day the Lord to be my God, Father, Saviour, and portion for ever. I am one of his covenant children for ever. Record, O eternal Lord, in thy book of remembrance that henceforth I am thine for ever. From this day I solemnly renounce all former lords—world, flesh, and devil—in thy name. No more, directly or indirectly, will I obey them. I renounced them many years ago, and I renounce them for ever. This day I give up myself to thee, a living sacrifice, holy and acceptable unto thee; which I know is my reasonable service. To thee I consecrate all my worldly possessions; in thy service I desire and purpose to spend all my time, desiring thee to teach me to spend every moment of it to thy glory and the setting forth of thy praise, in every station and relation of life I am now or may hereafter be in. And I earnestly pray that whatever influence thou mayest in any wise give me over others, thou wouldest give me strength and courage to exert it to the utmost to thy glory, resolving not only myself to do it, but that all others, so far as I can rationally and properly influence them, shall serve the Lord. In that cause would I, O Lord, steadfastly persevere to my last breath, steadfastly praying that every day of my life may supply the defects and correct the irregularities of the former; and that by divine grace I may be enabled not only in that happy way to hold on, but to grow daily more active in it. Nor do I only consecrate all I have to thy service, but I also most humbly resign and submit to thy holy and sovereign will all that I have. I leave, O Lord, to thy management and direction all I possess and all I wish, and set every enjoyment and interest before thee to be disposed of as thou pleasest. Continue or remove what thou hast given me, bestow or refuse what I imagine I want, as thou seest good; and though I dare not say I will never repine, yet I hope I may say I will labour not only to submit but to acquiesce; not only to bear thy heaviest afflictions on me, but to consent to them and praise thee for them; contentedly resolving, in all thy appointments, my will into thine; esteeming myself as nothing, and thee, O God, as the great Eternal All, whose word shall determine, and whose power shall order all things in the world.”

“Dispose my affairs, O God, in a manner which may be wholly subservient to thy glory and my own true happiness; and when I have done, borne, and endured thy will upon earth, call me home at what time and in what manner thou pleasest. Only grant that in my dying moments, and the near approach of eternity, I may remember this my engagement to thee, and may employ my latest breath in thy service; and do thou, when thou seest me in the agonies of death, remember this covenant , too, though I should be incapable of recollecting it. Look down upon me, O Lord, thy languishing, dying child; place thine everlasting arms underneath my head; put strength and confidence into my departing spirit, and receive it to the embrace of thine everlasting love.”

“And when I am thus numbered with the dead and all the interests of mortality are over with me for ever, if this solemn memorial should fall into the hands of any surviving friends or relations, may it be the means of making serious impressions on their minds, and may they read it not only as my language, but as their own, and learn to fear the Lord my God, and with me to put their trust under the shadow of his wings for time and for eternity.”

“I solemnly subscribe this dedication of myself to the ever-blessed Triune God, in the presence of angels and all invisible spectators, this fourth day of December 1752. WILLIAM GRIMSHAW.”

The next document from which I will supply some extracts, is a Creed or Summary of Belief which Grimshaw sent to Romaine in December 1762, only four months before his death. It is to be found at length in Middleton’s Biographia Evangelica. This creed is a regular systematic statement of Grimshaw’s religious views, drawn out into twenty-six heads, and is of course far too long to be inserted in this place. A few paragraphs are all that I can give the reader. They prove, at any rate, that, however much Grimshaw may have agreed with Wesley on many points, he certainly was not an Arminian.

22. I believe it is by the Spirit we are enabled, not to eradicate (as some affirm), for that is absurd, but to subjugate the old man; to suppress, not extirpate, the exorbitancies of our fleshly appetites; to resist and overcome the world and the devil, and to grow in grace gradually, not suddenly, unto the perfect and eternal day. This is all I acknowledge or know to be Christian perfection or sanctification.

23. I believe that all true believers will be daily tempted by the flesh, as well as by the world and the devil, even to their lives’ end; and they will feel an inclination, more or less, to comply, yea and do comply therewith. So that the best believer, if he knows what he says, and says the truth, is but a sinner at the best.

24. I believe that their minds are incessantly subject to a thousand impertinent, unprofitable thoughts, even amidst their reading, meditation, and prayers; that all their religious exercises are deficient; that all their graces, how eminent soever, are imperfect; that God sees iniquity in all their holy things; and though it be granted that they love God with all their hearts, yet they must continually pray with the psalmist, Enter not into judgment with thy servant.

25. But I believe that Jesus is a full as well as a free Saviour, the same yesterday, today, and for ever. He alone is not only the believer’s wisdom and righteousness, but his sanctification and redemption; and in him is a fountain ever open for sin and uncleanness unto the last breath of his life. This is my daily, necessary privilege, my relief, and my comfort.

26. I believe, lastly, that God is faithful and unchangeable; that all his promises are yea and amen; that he never, never will, as the apostle says, leave me; will never, never, never forsake me; but that I, and all that believe, love, and fear him, shall receive the end of our faith—the salvation of our souls.

“Here is the sum and substance of my creed. It is at least what I pre-sume to call my form of sound words. In it I can truly say I have no respect to men or books, ancient or modern, but to the Holy Scriptures, reason, and experience. According to this creed hitherto I have, and I hope hereafter to proceed in all my preaching, debasing man and exalting any dear Lord in all his offices.”

The last specimen that I will give of Grimshaw’s remains is a letter addressed by him to certain Christians in London. It is dated January 9, 1760, and is to be found in Hardy’s Life.

“Grace, mercy, and peace be to you from God our Father and from our Lord Jesus. It is well with some sorts of people that you have had, or now have to do with. It is well with those of you in Christ who are gone to God; it is well with those of you in Christ who are not gone to God; it is well with those of you who earnestly long to be in Christ, that they may go to God; it is well for those who neither desire to be in Christ nor to go to. God; and it is only bad with such who, being out of Christ, are gone to the devil. Them it is best to let alone, and say no more about them.

“It is well with those of you who, being in Christ, are gone to God. You, ministers and members of Christ, have no more doubt or pain about them. They are now and for ever out of the reach of the world, flesh, and devil. They are gone where the wicked cease from troubling, and where the weary are at rest. They are sweetly reposing in Abraham’s bosom. They dwell in His presence who hath redeemed them, where there is fulness of joy and pleasure for evermore. They are waiting the joyful morning of the resurrection, when their vile bodies shall be made like unto his glorious body, shall be re-united to the soul, shall receive the joyful sentence, and inherit the kingdom prepared for them from the foundation of the world.

“It is well also with those of you who are in Christ though not gone to God. You live next door to them. Heaven is begun with you too. The kingdom of God is within you; you feel it. This is a kingdom of righteousness, and peace, and joy in the Holy Ghost. It is begun in grace, and shall terminate in glory. Yea, it is Christ within you the hope of glory. Christ the rock, the foundation laid in your hearts, hope in the middle, and glory at the top. Christ, hope, glory! Christ, hope, glory! You are washed in the blood of the Lamb; justified, sanctified, and shall shortly be glorified. Yea, your lives are already hid with Christ in God. You have your conversation already in heaven. Already you sit in heavenly places in Christ Jesus. What heavenly sentences are these! What can come nearer Paradise? Bless the Lord, O ye happy souls, and let all that is within you bless his holy name. Sing unto the Lord as long as you live, and praise your God while you have your being. And how long will that be! Through the endless ages of a glorious eternity!

“It is well with all those of you who truly desire to be in Christ, that you may go to God. Surely he owns you. Your desires are from him; you shall. enjoy his favour. By-and-by you shall have peace with him through our Lord Jesus Christ. Go forth by the footsteps of the flock, and feed by the Shepherd’s tents. Be constant in every means of grace. He will be found of them that diligently seek him. Blessed are they that mourn, for they shall be comforted. Though your sins be never so many, never so monstrous, all shall be forgiven. He will have mercy upon you, and will abundantly pardon. For where sin bath abounded, grace doth much more abound. He who hath begun this good work in you will accomplish it to your eternal good and his eternal glory. Therefore doubt not, fear not; a broken and a contrite heart God will not despise. The deeper is your sorrow, the nearer is your joy. Your extremity is God’s opportunity. It is usually darkest just before daybreak. You shall shortly find pardon, peace, and plenteous redemption, and at last rejoice in the common and glorious salvation of his saints.

“And lastly, it is well for you who neither truly desire to be in Christ, nor to go to God. For it is well for you that you are not in hell. It is well your day of grace is not utterly past. Behold, now is your accepted time; behold, now is your day of salvation! Oh that you may employ the remainder of it in working out your salvation with fear and trembling. Now is faith to be had—saving faith. Now you may be washed from all sins in the Redeemer’s blood, justified, sanctified, and prepared for heaven. Take, I beseech you, the time, while the time is You have now the means of grace to use, the ordinances of God to enjoy, his Word to read and hear, his ministers to instruct you, and his members to converse with. You know not what a day may bring forth. You may die suddenly. As death leaves you judgment will find you. And if you should die as you are—out of Christ, void of true faith, unregenerate, unsanctified—fire and brimstone, storm and tempest, God will rain upon you, as your eternal, intolerable portion to drink.

“Suffer me, therefore, thus far, one and all of you. God’s glory and your everlasting salvation is all I aim at. What I look for in return from you is, I confess, much more than I deserve—your prayers.”

It would be easy to supply many more extracts than these. But I forbear. I make no apology, however, for the length of those I have already given. The reader will probably agree with me that they are in themselves full of interesting matter. But this is not all. They possess an additional value as supplying a most graphic picture of Grimshaw’s mode of expressing himself, and of the topics on which his mind was constantly dwelling. In fact, they furnish a pretty correct idea of what the good man’s preaching must have been. He evidently wrote as he thought and spoke. His remains are just the overflowing of a heart full of Scripture, full of Christ, full of deep thoughts on the sinfulness of sin, the value of the soul, the need of repentance and faith, the happiness of holy living, the importance of a world to come. Let a man analyze Grimshaw’s remains carefully and thoughtfully, and I suspect he will have a very fair conception of the style in which Grimshaw used to preach.

The anecdotes and traditions that have been handed down about the good Incumbent of Haworth are very many and very curious. All of them, perhaps, are not true. Some, perhaps, are greatly exaggerated. Many, however, after making every fair deduction, are undoubtedly credible and genuine. I will mention some of them.

The influence he gradually obtained in his own parish was very great. Even those who were not converted looked up to him and feared him. John Newton says: “One Sunday, as a man was passing through Haworth on horseback, his horse lost a shoe. He applied to a blacksmith to put it on. To his surprise, the man told him he could not shoe a horse on the Lord’s day without the minister’s leave. They went together to Mr. Grimshaw, and the man satisfying him that he was really in haste, going for a doctor, Mr. Grimshaw permitted the blacksmith to shoe the horse, which otherwise he would not have done for double pay.”

“It was his frequent custom,” adds Newton, “to leave the church at Haworth while the psalm before sermon was singing, to see if any were absent from worship and idling their time in the churchyard, the street, or the ale-houses; and many of those whom he so found he would drive into church before him. A friend of mine, passing a public-house in Haworth on a Lord’s day morning, saw several persons making their escape out of it, some jumping out of the lower windows, and some over a low wall. He was at first alarmed, fearing the house was on fire; but upon inquiring what was the cause of the commotion, he was only told that they saw the parson coming. They were more afraid of the parson than of a justice of the peace. His reproof was so authoritative, and yet so mild and friendly, that the stoutest sinner could not stand before him.

“He endeavoured likewise to suppress the common custom of walking in the fields on the Lord’s day in summer, instead of coming to God’s house. He not only bore his testimony against it from the pulpit, but went into the fields in person to detect and reprove the delinquents. There was a spot at some distance from the village, where many young people used to assemble on Sundays in spite of all his warnings. At last he disguised himself one evening, that he might not be known till he was near enough to discover who they were. He then threw off his disguise, and charged them not to move. He took down all their names with his pencil, and ordered them to attend on him on a day and hour which he appointed. They all waited on him accordingly, as punctually as if they had been served with a warrant. When they came, he led them into a private room, when, after forming them into a circle and commanding them to kneel down, he kneeled down in the midst of them, and prayed for them with much earnestness for a considerable time. After rising from his knees, he gave them a close and affecting lecture. He never had occasion to repeat this friendly discipline. He entirely broke the objectionable custom.”

One of the most remarkable and well-authenticated anecdotes about Grimshaw is in connection with Haworth races. These races were an annual festival got up by the innkeepers, and a great occasion of drunkenness, riot, profligacy, and confusion. For some time Grimshaw attempted in vain to stop these races. “At last,” says John Newton, “unable to prevail with men, he addressed himself to God. For some time before the races he made it a subject of fervent prayer that the Lord would be pleased to interfere, and to stop these evil proceedings in his own way. When the race-time came, the people assembled as usual, but they were soon dispersed. Before the races could begin, dark clouds covered the sky, and such excessively heavy rain fell, that the people could not remain on the ground, and it continued to rain incessantly during the three days appointed for the races. This event was much spoken of at Haworth. It became a sort of proverbial saying among the people that old Grimshaw put a stop to the races by his prayers. And it proved an effectual stop. There were no more races at Haworth.”

“He was particularly watchful,” says Newton, “over those of his flock who made an open profession of religion, to see if they adorned the doctrine of God our Saviour in all things, and maintained a consistent character; and he was very severe in his censures if he found any of his communicants guilty of wrong practices. When he suspected hypocrisy, he sometimes took such strange methods to detect it, as perhaps few men but himself would have thought of. He had a suspicion of the sincerity of some of his hearers, who made great pretence to religion. In order to find out one of them, he disguised himself as a poor man, and applied to him for relief and a lodging; and, behold! this person who wished to be thought very good and charitable, treated him with some abuse.—He then went to another house, to a woman who was almost blind. He touched her gently with his stick, and went on doing it until she, supposing it was done by some children in the neighbourhood, began not only to threaten but to swear at them. Thus he was confirmed in his apprehensions.”

“At a cottage prayer meeting,” says Hardy, “some of Grimshaw’s people had to endure much annoyance and persecution, and for a long time no one could discover who the delinquents were. At last the incumbent came to their assistance and solved the mystery. He put on an old woman’s cap, and peeped stealthily from behind the door, and then appeared to grow rather bolder, while he quietly made the observation he wished. He found there was a set of rude boys who only came to make sport and annoy others. They soon began to make fun of the old woman (as she seemed to be), and defied her with mocks and menaces. In this way they were all found out and brought to justice, and then the persecution ceased.”

He carried his humility and simplicity of living to such an extent that he thought anything good enough for himself, if he could only show a Christian brother kindness and hospitality. A godly friend who once came to stay a night with him, was horrified on looking out of his bedroom window in the morning, to see Grimshaw with his own hands cleaning his guest’s boots! Nor was this all. On coming down stairs he discovered that Grimshaw had actually given up his own bedroom for his accommodation, and had spent the night in a hay-loft!

His ways in his own parish, as he went about doing the work of a pastor, were very peculiar. Hardy says, “When he met with anyone in the lanes he would enter into familiar conversation with them, and generally asked if they were accustomed to pray. When they answered in the affirmative, and he doubted their sincerity, he bade them kneel down and show him how they performed this duty. There were sometimes scenes by the road-side, in consequence, that a stranger could not look at without a smile; but to the persons concerned these inquiries were, in some instances, the means of awakening concern about their souls. The tradition of the district is, that he would rive them from horseback to make them pray.’ But he was as ready to do an act of courtesy as to administer reproof. Once on his way to Colne, he overtook an old woman, and asked her where she was going. She replied, ‘To hear Grimshaw.’ He pitied her many infirmities; but she said her heart was already there, and she would make the body follow. Struck by her earnestness, he actually took her up behind him on the pillion of his own horse, and thus enabled her to reach the place without further toil.”

Hardy adds, “Grimshaw was not unmindful of himself, whilst watchful over the souls of others. Once he had a very fine cow, in which he took so much pride, that the thought of her followed him into the service of the Church, and hindered his communion with God. He determined that she should no longer ruffle his mind, and so announced her for sale. When a farmer came to look at her, he asked, as usual, whether she had any fault. To this Grimshaw made this quaint reply, Her fault in my eyes will be no fault to you; she follows me into my pulpit.”

The things that he did inside his church, both in the reading-desk and the pulpit, may certainly seem to us very eccentric and strange in the present day. Undoubtedly, they are not examples for imitation; and unless a man is “a Grimshaw,” he has no right to attempt them. Before condemning them too strongly, however, men should call to mind the times and the population with which he had to do. We are, in fact, dealing with a man who lived a hundred years ago.

He was very particular in enforcing order and devout behaviour among the worshippers in his church at Haworth. Carelessness and inattention were instantly observed and openly rebuked; and he would not proceed with the service until he saw every person present in the attitude of devotion. Some of his hearers certainly deserved great attention and encouragement. Not a few came ten or twelve miles every Sunday to attend his ministry. One John Madden of Bacup often walked to Haworth on the Sabbath, and returned the same evening, a distance, out and home, of nearly forty miles.

In giving out the hymns to be sung in church, he sometimes took singular liberties. A valued friend of mine was told by an old man in Haworth that he remembered his grandfather speaking of Grimshaw, and telling the following story:—His grandfather was in Haworth Church, when Grimshaw gave out the well-known hymn of Dr. Watts, beginning,—

“Come, ye that love the Lord,

And let your joys be known;

Join in a song with sweet accord,

And so surround the throne.”

He said, that when Grimshaw had read the first verse, he looked at the people, and cried out, “Now, unconverted sinners here present, can you sing that?”