Daniel Rowlands – 1713–1790

Daniel Rowlands

This sketch of Daniel Rowlands first appeared in ‘The Family Treasury’ along with eight other pen sketches of 18th century divines. They were published together as ‘Christian Leaders of the Last Century.’

Daniel Rowlands ranks as one of the most effective Welsh preachers of all time.

Chapter I. Daniel Rowlands

Born in Wales 1713—Educated at Hereford, and never at a University—Ordained 1733— Curate of Llangeitho—An Altered Man in 1738—Extraordinary Effect of his Preaching—Extra-parochial and Out-door Preaching—License Withdrawn by the Bishop in 1763—Continues to Preach in a Chapel at Llangeitho—Died 1790—Account of his Portrait.

One of the greatest spiritual champions of the last century whom I wish to introduce to my readers in this chapter, is one who is little known. The man I mean is the Rev. Daniel Rowlands of Llangeitho in Cardiganshire. Thousands of my countrymen, I suspect, have some little acquaintance with Whitefield, Wesley, and Romaine, who never even heard the name of the great apostle of Wales.

That such should be the case need not surprise us. Rowlands was a Welsh clergyman, and seldom preached in the English language. He resided in a very remote part of the Principality, and hardly ever came to London. His ministry was almost entirely among the middle and lower classes in about five counties in Wales.

These circumstances alone are enough to account for the fact that so few people know anything about him. Whatever the causes may be there are not many Englishmen who understand Welsh, or can even pronounce the names of the parishes where Rowlands used to preach. In the face of these circumstances, we have no right to be surprised if his reputation has been confined to the land of his nativity.

In addition to all this, we must remember that no biographical account of Rowlands was ever drawn up by his contemporaries. Materials for such an account were got together by one of his sons, and forwarded to Lady Huntingdon. Her death, unfortunately, immediately afterwards, prevented these materials being used, and what became of them after her death has never been ascertained. The only memoirs of Rowlands are two lives, written by clergymen who are still living.

They are both excellent and useful in their way, but of course they labour under the disadvantage of having been drawn up long after the mighty subject of them had passed away.*

These two volumes, and some very valuable information which I have succeeded in obtaining from a kind correspondent in Wales, are the only mines of matter to which I have had access in drawing up this memoir.

Enough, however, and more than enough, is extant, to prove that Daniel Rowlands, in the highest sense, was one of the spiritual giants of the last century. It is a fact that Lady Huntingdon, no mean judge of clergymen, had the highest opinion of Rowlands. Few people had better opportunities of forming a judgment of preachers than she had, and she thought Rowlands was second only to Whitefield.

It is a fact that no British preacher of the last century kept together in one district such enormous congregations of souls for fifty years as Rowlands did. It is a fact, above all, that no man a hundred years ago seems to have preached with such unmistakable power of the Holy Ghost accompanying him as Rowlands.

These are great isolated facts that cannot be disputed. Like the few scattered bones of extinct mammoths and mastodons, they speak volumes to all who have an ear to hear. They tell us that, in considering and examining Daniel Rowlands, we are dealing with no common man.

*The memoirs of Rowlands to which I refer are two small volumes by the Rev. John Owen, Rector of Trussington, and the Rev. E. Morgan, Vicar of Syston, both in the county of Leicester. The private information which I have received has been supplied by a relative of the great Welsh apostle, though not in lineal descent, the Rev. William Rowlands of Fishguard, South Wales. Some few facts, it may be interesting to my readers to know, come from an old man of eighty-five, who, when a boy, heard Rowlands preach.

Daniel Rowlands was born in the year 1713, at Pant-y-.beudy in the parish of Llancwnlle, near Llangeitho, Cardiganshire. He was the second son of the Rev. Daniel Rowlands, rector of Llangeitho, by Jennet, his wife. When a child of three yearsold, he had a narrow escape of death, like John Wesley. A large stone fell down the chimney on the very spot where he had been sitting two minutes before, which, had he not providentially moved from his place, must have killed him.

Nothing else is known of the first twenty years of his life, except the fact that he received his education at Hereford Grammar School, and that he lost his father when he was eighteen years old. It appears, from a tablet in Llangeitho Church, that when Rowlands was born, his father was fifty-four and his mother forty-five years old. His father’s removal could not therefore have been a premature event, as he must have attained the ripe age of seventy-two.

From some cause or other, of which we can give no account, Rowlands appears to have gone to no University. His father’s death may possibly have made a difference in the circumstances of the family. At any rate, the next fact we hear about him after his father’s death, is his ordination in London at the early age of twenty, in the year 1733. He was ordained by letters dimissory from the Bishop of St. David’s, and it is recorded, as acurious proof both of his poverty and his earnestness of character, that he went to London on foot.

The title on which Rowlands was ordained was that of curate to his elder brother John, who had succeeded his father, and held the three adjacent livings of Llangeitho, Llancwnlle, and Llandewibrefi. He seems to have entered on his ministerial duties like thousands in his clay—without the slightest adequate sense of his responsibilities, and utterly ignorant of the gospel of Christ. According to Owen he was a good classical scholar, and had made rapid progress at Hereford School in all secular learning.

But in the neighbourhood where he was born and began his ministry, he is reported never to have given any proof of fitness to be a minister. He was only known as a man remarkable for natural vivacity, of middle size, of a firm make, of quick and nimble action, very adroit and successful in all games and athletic amusements, and as ready as any one, after doing duty in church on Sunday morning, to spend the rest of God’s day in sports and revels, if not in drunkenness.

Such was the character of the great apostle of Wales for some time after his ordination! He was never likely, afterwards, to forget St. Paul’s words to the Corinthians, “Such were some of you” (I Cor. VI. II), or to doubt the possibility of any one’s conversion.

The precise time and manner of Rowlands’ conversion are points involved in much obscurity. According to Morgan, the first thing that awakened him out of his spiritual slumber, was the discovery that, however well he tried to preach, he could not prevent one of his congregations being completely thinned by a dissenting minister named Pugh. It is said that this made him alter his sermons, and adopt a more awakening and alarming style of address.

According to Owen, he was first brought to himself by hearing a well-known excellent clergyman, named Griffith Jones, preach at Llandewibrefi. On this occasion his appearance, as he stood in the crowd before the pulpit, is said to have been so full of vanity, conceit, and levity, that Mr. Jones stopped in his sermon and offered a special prayer for him, that God would touch his heart, and make him an instrument for turning souls from darkness to light.

This prayer is said to have had an immense effect on Rowlands, and he is reported to have been a different man from that day. I do not attempt to reconcile the two accounts. I can quite believe that both are true. When the Holy Ghost takes in hand the conversion of a soul, he often causes a variety of circumstances to concur and co-operate in producing it.

This, I am sure, would be the testimony of all experienced believers. Owen got hold of one set of facts, and Morgan of another. Both happened probably about the same time, and both probably are true.

One thing, at any rate, is very certain. From about the year I738, when Rowlands was twenty-five, a complete change came over his life and ministry. He began to preach like a man in earnest, and to speak and act like one who had found out that sin, and death, and judgment, and heaven, and hell, were great realities. Gifted beyond most men with bodily and mental qualifications for the work of the pulpit, he began to consecrate himself wholly to it, and threw himself, body, and soul, and mind, into his sermons.

The consequence, as might be expected, was an enormous amount of popularity. The churches where he preached were crowded to suffocation. The effect of his ministry, in the way of awakening and arousing sinners, was something tremendous. “The impression,” says Morgan, “on the hearts of most people, was that of awe and distress, and as if they saw the end of the world drawing near, and hell ready to swallow them up. His fame soon spread throughout the country, and people came from all parts to hear him.

Not only the churches were filled, but also the churchyards. It is said that, under deep conviction, numbers of the people lay down on the ground in the churchyard of Llancwnlle, and it was not easy for a person to pass by without stumbling against some of them.”

At this very time, however curious it may seem, it is clear that Rowlands did not preach the full gospel. His testimony was unmistakably truth, but still it was not the whole truth. He painted the spirituality and condemning power of the law in such vivid colours that his hearers trembled before him, and cried out for mercy.

But he did not yet lift up Christ crucified in all his fulness, as a refuge, a physician, a redeemer, and a friend; and hence, though many were wounded, they were not healed. How long he continued preaching in this strain it is, at this distance of time, extremely difficult to say.

So far as I can make out by comparing dates, it went on for about four years. The work that he did for God in this period, I have no doubt, was exceedingly useful, as a preparation for the message of later days. I, for one, believe that there are places, and times, and seasons, and congregations, in which powerful preaching of the law is of the greatest value.

I strongly suspect that many evangelical congregations in the present day would be immensely benefited by a broad, powerful exhibition of God’s law. But that there was too much law in Rowlands’ preaching for four years after his conversion, both for his own comfort and the good of his hearers, is very evident from the fragmentary accounts that remain of his ministry.

The means by which the mind of Rowlands was gradually led into the full light of the gospel have not been fully explained by his biographers. Perhaps the simplest explanation will be found in our Lord Jesus Christ’s words, “If any man will do his will, he shall know of the doctrine” (John VII. 17). Rowlands was evidently a man who honestly lived up to his light, and followed on to know the Lord. His Master took care that he did not long walk in darkness, but showed him “the light of life.”

One principal instrument of guiding him into the whole truth was that same Mr. Pugh who, at an earlier period, had thinned his congregation! He took great interest in Rowlands at this critical era in his spiritual history, and gave him much excellent advice. “Preach the gospel, dear sir,” he would say; “ preach the gospel to the people, and apply the balm of Gilead, the blood of Christ, to their spiritual wounds, and show the necessity of faith in the crucified Saviour.”

Happy indeed are young ministers who have an Aquila or Priscilla near them, and when they get good advice are willing to listen to it! The friendship of the eminent layman, Howell Harris, with whom Rowlands became acquainted about this time, was no doubt a great additional help to his soul.

In one Way or another, the great apostle of Wales was gradually led into the full noontide light of Christ’s truth; and about the year I742, in the thirtieth year of his age, became established as the preacher of a singularly full, free, clear, and well-balanced gospel.

The effect of Rowlands’ ministry from this time forward to his life’s end was something so vast and prodigious, that it almost takes away one’s breath to hear of it. We see unhappily so very little of spiritual influences in the present day, the operations of the Holy Ghost appear confined within such narrow limits and to reach so few persons, that the harvests reaped at Llangeitho a hundred years ago sound almost incredible.

But the evidence of the results of his preaching is so abundant and incontestable, that there is no room left for doubt. One universal testimony is borne to the fact that Rowlands was made a blessing to hundreds of souls. People used to flock to hear him preach from every part of the Principality, and to think nothing of travelling fifty or sixty miles for the purpose.

On sacrament Sundays it was no uncommon thing for him to have I500, or 2000, or even 2500 communicants! The people on these occasions would go together in companies, like the Jews going up to the temple feast in Jerusalem, and would return home afterwards singing hymns and psalms on their journey, caring nothing for fatigue.

It is useless to attempt accounting for these effects of the great Welsh preacher’s ministry, as many do, by calling them religious excitement Such people would do well to remember that the influence which Rowlands had over his hearers was an influence which never waned for at least forty-eight years. It had its ebbs and flows, no doubt, and rose on several occasions to the spring-tide of revivals; but at no time did his ministry appear to be without immense and unparalleled results.

According to Charles of Bala, and many other unexceptionable witnesses, it seemed just as attractive and effective when he was seventy years old as it was when he was fifty.

When we recollect, moreover, the singular fact that on Sundays, at least, Rowlands was very seldom absent from Llangeitho, and that for forty-eight years he was constantly preaching on the same spot, and not, like Whitefield and Wesley, incessantly addressing fresh congregations, we must surely allow that few preachers have had such extraordinary spiritual success since the days of the apostles.

Of course it would be absurd to say that there was no excitement, unsound profession, hypocrisy, and false fire among the thousands who crowded to hear Rowlands. There was much, no doubt, as there always will be, when large masses of people are gathered together. Nothing, perhaps, is so infectious as a kind of sham, sensational Christianity, and particularly among unlearned and ignorant men. The Welsh, too, are notoriously an excitable people.

No one, however, was more fully alive to these dangers than the great preacher himself and no one could warn his hearers more incessantly that the Christianity which was not practical was unprofitable and vain. But, after all, the effects of Rowlands’ ministry were too plain and palpable to be mistaken.

There is clear and overwhelming evidence that the lives of many of his hearers were vastly improved after hearing him preach, and that sin was checked and distinct knowledge of Christianity increased to an immense extent throughout the Principality.

It will surprise no Christian to hear that, from an early period, Rowlands found it impossible to confine his labours to his own parish. The state of the country was so deplorable as to religion and morality, and the applications he received for help were so many, that he felt he had no choice in the matter. The circumstances under which he first began preaching out of his own neighbourhood are so interesting, as described by Owen, that I shall give his words without abbreviation:

“There was a farmer’s wife in Ystradffin, in the county of Carmarthen, who had a sister living near Llangeitho. This woman came at times to see her sister, and on one of these occasions she heard some strange things about the clergyman of the parish—that is, Rowlands. The common saying was, that he was not right in his mind. However, she went to hear him, and not in vain; but she said nothing then to her sister or to anybody else about the sermon, and she returned home to her family.

The following Sunday she came again to her sister’s home at Llangeitho. ‘What is the matter?’ said her sister, in great surprise. ‘Are your husband and your children well?’ She feared, from seeing her again so soon and so unexpectedly, that something unpleasant had happened.

‘Oh, yes,’ was the reply, ‘nothing of that kind is amiss.’ Again she asked her, ‘what, then, is the matter? ‘ To this she replied, I don’t well know what is the matter. Something that your crackedclergyman said last Sunday has brought me here to day. It stuck in my mind all the week, and never left me night nor day.’ She went again to hear, and continued to come every Sunday, though her road was rough and mountainous, and her home more than twenty miles from Llangeitho.

“After continuing to hear Rowlands about half a year, she felt a strong desire to ask him to come and preach at Ystradffin. She made up her mind to try; and, after service one Sunday, she went to Rowlands, and accosted him in the following manner : ‘Sir, if what you say to us is true, there are many in my neighbourhood in a most dangerous condition, going fast to eternal misery. For the sake of their souls, come over, sir, to preach to them.’

The woman’s request took Rowlands by surprise; but without a moment’s hesitation he said, in his usual quick way, ‘ Yes, I will come, if you can get the clergyman’s permission.’ This satisfied the woman, and she returned home as much pleased as if she had found some rich treasure. She took the first opportunity of asking her clergyman’s permission, and easily succeeded. Next Sunday she went joyfully to Llangeitho, and informed Rowlands of her success.

According to his promise he went over and preached at Ystradffin, and his very first sermon there was wonderfully blessed. Not less than thirty persons, it is said, were converted that day. Many of them afterwards came regularly to hear him at Llangeitho.”

From this time forth, Rowlands never hesitated to preach outside his own parish, wherever a door of usefulness was opened. When he could, he preached in churches. When churches were closed to him, he would preach in a room, a barn, or the open air. At no period, however, of his ministerial life does he appear to have been so much of an itinerant as some of his contemporaries.

He rightly judged that hearers of the gospel required to be built up as well as awakened, and for this work he was peculiarly well qualified. Whatever, therefore, he did on week days, the Sunday generally found him at Llangeitho.

The circumstances under which he first began the practice of field-preaching were no less remarkable than those under which he was called to preach at Ystradffin. It appears that after his own conversion he felt great anxiety about the spiritual condition of his old companions in sin and folly. Most of them were thoughtless headstrong young men, who thoroughly disliked his searching sermons, and refused at last to come to church at all.

“Their custom,” says Owen, “was to go on Sunday to a suitable place on one of the hills above Llangeitho, and there amuse themselves with sports and games.” Rowlands tried all means to stop this sinful profanation of the Lord’s day, but for some time utterly failed. At last he determined to go there himself on a Sunday. As these rebels against God would not come to him in church, he resolved to go to them on their own ground.

He went therefore, and suddenly breaking into the ring as a cockfight was going on, addressed them powerfully and boldly about the sinfulness of their conduct. The effect was so great that not a tongue was raised to answer or oppose him, and from that day the Sabbath assembly in that place was completely given up. For the rest of his life Rowlands never hesitated, when occasion required, to preach in the open air.

The extra-parochial work that Rowlands did by his itinerant preaching was carefully followed up and not allowed to fall to the ground. No one understood better than he did, that souls require almost as much attention after they are awakened as they do before, and that in spiritual husbandry there is need of watering as well as planting.

Aided, therefore, by a few zealous fellow-labourers, both lay and clerical, he established a regular system of Societies, on John Wesley’s plan, over the greater part of Wales, through which he managed to keep up a con-stant communication with all who valued the gospel that he preached, and to keep them well together.

These societies were all connected with one great Association, which met four times a-year, and of which he was generally the moderator. The amount of his influence at these Association-meetings may be measured by the fact that above one hundred ministers in the Principality regarded him as their spiritual father! From the very first this Association seems to have been a most wisely organized and useful institution, and to it may be traced the existence of the Calvinistic Methodist body in Wales at this very day.

The mighty instrument whom God employed in doing all the good works I have been describing, was not permitted to do them without many trials. For wise and good ends, no doubt – to keep him humble in the midst of his immense success and to prevent his being exalted overmuch—he was called upon to drink many bitter cups. Like his divine Master, he was “a man of sorrows and acquainted with grief.”

The greatest of these trials, no doubt, was his ejection from the Church of England in 1763, after serving her faithfully for next to nothing as an ordained clergyman for thirty years. The manner in which this disgraceful transaction was accomplished was so remarkable, that it deserves to be fully described.

Rowlands, it must be remembered, was never an incumbent. From the time of his ordination in 1733, he was simply curate of Llangeitho, under his elder brother John, until the time of his death in 1760. What kind of a clergyman his elder brother was is not very clear. He was drowned at Aberystwith, and we only know that for twenty-seven years he seems to have left everything at Llangeitho in Daniel’s hands, and to have let him do just what he liked.

Upon the death of John Rowlands, the Bishop of St. David’s, who was patron of Llangeitho, was asked to give the living to his brother Daniel, upon the very reasonable ground that he had been serving the parish as curate no less than twenty-seven years I The bishop unhappily refused to comply with this request, alleging as his excuse that he had received many complaints about his irregularities.

He took the very singular step of giving the living to John, the son of Daniel Rowlands, a young man twenty-seven years old. The result of this very odd proceeding was, that Daniel Rowlands became curate to his own son, as he had been curate to his own brother, and continued his labours at Llangeitho for three years more uninterruptedly.*

* For a clue to all this intricacy, I am entirely indebted to the Rev. W. Rowlands of Fishguard. Unless the facts I have detailed are carefully remembered, it is impossible to understand how Daniel Rowlands was so easily turned out of his position. The truth is that he was only a curate,

The reasons why the Bishop of St. David’s refused to give Rowlands the living of Llangeitho may be easily divined. So long as he was only a curate, he knew that he could easily silence him. Once instituted and inducted as incumbent, he would have occupied a position from which he could not have been removed without much difficulty.

Influenced, probably, by some such considerations, the bishop permitted Rowlands to continue preaching at Llangeitho as curate to his son, warning him at the same time that the Welsh clergy were constantly complaining of his irregularities, and that he could not long look over them. These “irregularities,” be it remembered, were neither drunkenness, breach of the seventh commandment, hunting, shooting, nor gambling! The whole substance of his offence was preaching out of his own parish wherever he could get hearers.

To the bishop’s threats Rowlands replied, “that he had nothing in view but the glory of God in the salvation of sinners, and that as his labours had been so much blessed he could not desist.”

At length, in the year I763, the fatal step was taken. The bishop sent Rowlands a mandate, revoking his license, and was actually foolish enough to have it served on a Sunday! The niece of an eye-witness describes what happened in the following words “My uncle was at Llangeitho church that very morning. A stranger came forward and served Mr. Rowlands with a notice from the bishop, at the very time when he was stepping into the pulpit.

Mr. Rowlands read it, and told the people that the letter which he had just received was ‘from the bishop, revoking his license. Mr. Rowlands then said, ‘We must obey the higher powers. Let me beg you will go out quietly, and then we shall conclude the service of the morning by the church gate.’ And so they walked out, weeping and crying. My uncle thought there was not a dry eye in the church at the moment. Mr. Rowlands accordingly preached outside the church with extraordinary effect.”

A more unhappy, ill-timed, blundering exercise of Episcopal power than this, it is literally impossible to conceive! Here was a man of singular gifts and graces, who had no objection to anything in the Articles or Prayer-book, cast out of the Church of England for no other fault than excess of zeal. And this ejection took place at a time when scores of Welsh clergymen were shamefully neglecting their duties, and too often were drunkards, gamblers, and sportsmen, if not worse!

That the bishop afterwards bitterly repented of what he did, is very poor consolation indeed. It was too late. The deed was done. Rowlands was shut out of the Church of England, and an immense number of his people all over Wales followed him. A breach was made in the walls of the Established Church which will probably never be healed. As long as the world stands, the Church of England in Wales will never get over the injury done to it by the preposterous and stupid revocation of Daniel Rowlands’ license.

There is every reason to believe that Rowlands felt his expulsion most keenly. However, it made no difference whatever in his line of action. His friends and followers soon built him a large and commodious chapel in the parish of Llangeitho, and migrated there in a body.

He did not even leave Llangeitho rectory; for his son, being rector, allowed him to reside there as long as he lived. In fact, the Church of England lost everything by ejecting him, and gained nothing at all. The great Welsh preacher was never silenced practically for a single day, and the Church of England only reaped a harvest of odium and dislike in Wales, which is bearing fruit to this very hour.

From the time of his ejection to his death, the course of Rowlands’ life seems to have been comparatively undisturbed. No longer persecuted and snubbed by ecclesiastical superiors, he held on his way for twenty-seven years in great quietness, undiminished popularity, and immense usefulness, and died at length in Llangeitho rectory on October the I6th, 1790, at the ripe old age of seventy-seven.

“He was unwell during the last year of his life,” says Morgan, “but able to go on with his ministry at Llangeitho, though he scarcely went anywhere else. It was his particular wish that he might go direct from his work to his everlasting rest, and not be kept long on a death-bed. His heavenly Father was pleased to grant his desire, and when his departure was drawing nigh, he had some pleasing idea of his approaching end.”

One of his children has supplied the following interesting account of his last days :

“My father made the following observations in his sermons two Sundays before his departure. He said, ‘I am almost leaving, and am on the point of being taken from you. I am not tired of work, but in it. I have some presentiment that my heavenly Father will soon release me from my labours, and bring me to my everlasting rest But I hope that he will continue his gracious presence with you after I am gone.’

He told us, conversing on his departure after worship the last Sunday, that he should like to die in a quiet, serene manner, and hoped that he should not be disturbed by our sighs and crying. He added, ‘I have no more to state, by way of acceptance with God, than I have always stated: I die as a poor sinner, depending fully and entirely on the merits of a crucified Saviour for my acceptance with God.’ In his last hours he often used the expression, in Latin, which Wesley used on his death-bed, ‘God is with us;’ and finally departed in great peace.”

Rowlands was buried at Llangeitho, at the east end of the church. His enemies could shut him out of the pulpit, but not out of the churchyard. An old inhabitant of the parish, now eighty-five years of age, says: “I well remember his tomb, and many times have I read the inscription, his name, and age, with that of his wife’s, Eleanor, who died a year and two months after her husband. The stone was laid on a three feet wall, but it is now worn out by the hand of time.”

Rowlands was once married. It is believed that his wife was the daughter of Mr. Davies of Glynwchaf near Llangeitho. He had seven children who survived him, and two who died in infancy. What became of all his family, and whether there are any lineal descendants of his, I have been unable to ascertain with accuracy.

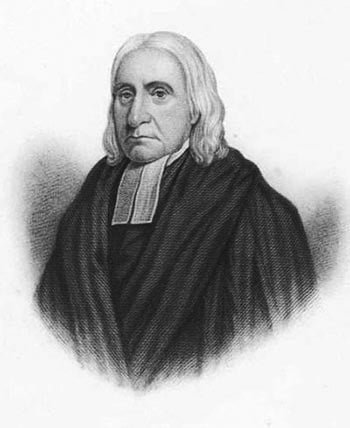

The engraving of him which faces the title-page of the lives drawn up by Morgan and Owen, gives one the idea of Rowlands being a grave and solemn-looking man. It is probably taken from the picture of him, which Lady Huntingdon sent an artist to take at the very end of his life.

The worthy old saint did not at all like having his portrait taken. “Why do you object, sir?” said the artist at last. “Why?” replied the old man, with great emphasis; “I am only a bit of clay like thyself” And then he exclaimed, “Alas! alas! alas! Taking the picture of a poor old sinner! alas! alas! “His countenance” says Morgan, “altered and fell at once, and this is the reason why the picture appears so heavy and cast down.”

I have other things yet to tell about Rowlands. His preaching and the many characteristic anecdotes about him deserve special notice. But I must reserve these points for another chapter.

Chapter II. Analysis of His Preaching & etc.

Analysis of his Preaching—Much of Christ—Richness of Thought—Felicity of Language—Large Measure of Practical and Experimental Teaching—Manner, Delivery, and Voice—Christmas Evans’ Description of his Preaching—Testimony of Mr. Jones of Creaton—Specimens of Rowlands’ Sermons—Inner Life and Private Character— Humility, Prayerfulness, Diligence, Self-Denial, Courage, Fervour—Rowland Hill’s Anecdote.

IN taking a general survey of the ministry of Daniel Rowlands of Liangeitho, the principal thing that strikes one is the extraordinary power of his preachingThere was evidently something very uncommon about his sermons. On this point we have the clear and distinct testimony of a great cloud of witnesses. In a day when God raised up several preachers of very great power, Rowlands was considered by competent judges to be equalled by only one man, and to be excelled by none.

Whitefield was thought to equal him; but even Whitefield was not thought to surpass him. This is undoubtedly high praise. Some account of the good man’s sermons will probably prove interesting to most of my readers. What were their peculiar characteristics? What were they like?

I must begin by frankly confessing that the subject is surrounded by difficulties. The materials out of which we have to form our judgment are exceedingly small. Eight sermons, translated out of Welsh into English in the year I774, are the only literary record which exists of the great Welsh apostle’s fifty years’ ministry.

Besides these sermons, and a few fragments of occasional addresses, we have hardly any means of testing the singularly high estimate, which his contemporaries formed of his preaching powers. When I add to this, that the eight sermons extant appear to be poorly translated, the reader will have some idea of the difficulties I have to contend with.

Let me remark, however, once for alt that when the generation, which heard a great preacher, has passed away, it is often hard to find out the secret of his popularity. No well-read person can be ignorant that Luther and Knox in the sixteenth century, Stephen Marshall in the Commonwealth times, and George Whitefield in the eighteenth century, were the most popular and famous preachers of their respective eras.

Yet no one, perhaps, can read their sermons, as we now possess them, without a secret feeling that they do not answer to their reputation. In short, it is useless to deny that there is some hidden secret about pulpit power, which baffles all attempts at definition.

The man, who attempts to depreciate the preaching of Rowlands on the ground that the only remains of him now extant seem poor, will find that he occupies an untenable position. He might as well attempt to depreciate the great champions of the German and Scottish Reformations.

After all, we must remember that no man has a right to pass unfavourable criticisms on the remains of great popular preachers, unless he has first thoroughly considered what kind of thing a popular sermon must of necessity be. The vast majority of sermon-hearers do not want fine words, close reasoning, deep philosophy, metaphysical abstractions, nice distinctions, elaborate composition, profound learning.

They delight in plain language, simple ideas, forcible illustrations, direct appeals to heart and conscience, short sentences, fervent, loving earnestness of manner. He who possesses such qualifications will seldom preach to empty benches. He who possesses them in a high degree will always be a popular preacher.

Tried by this standard, the popularity of Luther and Knox is easily explained. Rowlands appears to have been a man of this stamp. An intelligent judge of popular preaching can hardly fail to see in his remains, through all the many disadvantages under which we read them, some of the secrets of his marvellous success.

Having cleared my way by these preliminary remarks, I will proceed at once to show my readers some of the leading characteristics of the great Welsh evangelist’s preaching. I give them as the result of a close analysis of his literary remains. Weak and poor as they undoubtedly look in the garb of a translation, I venture to think that the following points stand out clearly in Rowlands’ sermons, and give us a tolerable idea of what his preaching generally was.

The first thing that I notice in the remains of Rowlands is the constant presence of Christ in all his addresses. The Lord Jesus stands out prominently in almost every page. That his doctrine was always eminently “evangelical” is a point on which I need not waste words. The men about whom I am writing were all men of that stamp. But of all the spiritual champions of last century, none appear to me to have brought Christ forward more prominently than Rowlands.

The blood, the sacrifice, the righteousness, the kindness, the patience, the saving grace, the example, the greatness of the Lord Jesus, are subjects which appear to run through every sermon, and to crop out at every turn. It seems as if the preacher could never say enough about his Master, and was never weary of commending him to his hearers. His divinity and his humanity, his office and his character, his death and his life, are pressed on our attention in every possible connection.

Yet it all seems to come in naturally, and without effort, as if it were the regular outfiowing of the preacher’s mind, and the language of a heart speaking from its abundance. Here, I suspect, was precisely one of the great secrets of Rowlands’ power. A ministry full of the Lord Jesus is exactly the sort of ministry that I should expect God to bless. Christ-honouring sermons are just the sermons that the Holy Spirit seals with success.

The second thing that I notice in the remains of Rowlands is a singular richness of thought and matter. Tradition records that he was a diligent student all his life, and spent a great deal of time in the preparation of his sermons. I can quite believe this. Even in the miserable relics, which we possess, I fancy I detect strong internal evidence that he was deeply read in Puritan divinity. I suspect that he was very familiar with the writings of such men as Gurnall, Watson, Brooks, Clarkson, and their contemporaries, and was constantly storing his mind with fresh thoughts from their pages.

Those who imagine that the great Welsh preacher was nothing but an empty declaimer of’ trite commonplaces, bald platitudes, and hackneyed phrases, with a lively manner and a loud voice, are utterly and entirely mistaken. They will find, even in the tattered rags of his translated sermons, abundant proof that Rowlands was a man who read much and thought much, and gave his hearers plenty to carry away. Even in the thin little volume of eight sermons, which I have, I find frequent quotations from Chrysostom, Augustine, Ambrose, Bernard, and Theophylact.

I find frequent reference to things recorded by Greek and Latin classical writers. I mark such names as Homer, Socrates, Plato, Æschines, Aristotle, Pythagoras, Carneades. Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar, Nero, the Augean stable, Thersites, and Xantippe, make their appearance here and there. That Rowlands was indebted to his friends the Puritans for most of these materials; I make no question at all. But wherever he may have got his learning, there is no doubt that he possessed it, and knew how to make use of it in his sermons.

In this respect I think he excelled all his contemporaries. Not one of them shows so much reading in his sermons as the curate of Llangeitho. Here again, I venture to suggest, was one great secret of Rowlands’ success. The man who takes much pains with his sermons, and never brings out what has “cost him nothing,” is just the man I expect God will bless. We want well beaten oil for the service of the sanctuary.

The third thing that I notice in the remains of Rowlands is the curious felicity of thelanguagein which he expressed his ideas. Of course this is a point on which I must speak diffidently, knowing literally nothing of the Welsh tongue, and entirely dependent on translation. But it is impossible to mistake certain peculiarities in style, which stand forth prominently in everything, which comes from the great Welsh apostle’s mind.

He abounds in short, terse, pithy, epigrammatic, proverbial sentences, of that kind which arrests the attention and sticks in the memory of hearers. He has a singularly happy mode of quoting Scriptures in confirming and enforcing the statement he makes. Above all, he is rich in images and illustrations, drawn from everything almost in the world, but always put in such a way that the simplest mind can understand them. Much of the peculiar interest of his preaching,

I suspect, may be traced to this talent of putting things in the most vivid and pictorial way. He made his hearers feel that they actually saw the things of which he was speaking. No intelligent reader of the Bible, I suppose, needs to be reminded that in all this Rowlands walked in the footsteps of his divine Master.

The sermons of Him who “spake as never man spake,” were not elaborate rhetorical arguments. Parables founded on subjects familiar to the humblest intellect, terse, broad, sententious statements, were the staple of our Lord Jesus Christ’s preaching. Much of the marvellous success of Rowlands, perhaps, may be traced up to his wise imitation of the best of patterns, the great Head of the Church.

The fourth and last thing, which I notice in the remains of Rowlands, is the large measure of practical and experimental teachingwhich enters into all his sermons. Anxious as he undoubtedly was to convert sinners and arouse the careless, he never seems to forget the importance of guiding the Church of God and building up believers. Warnings, counsels, encouragements, consolations suited to professing Christians, are continually appearing in all his discourses.

The peculiar character of his ministerial position may partly account for this. He was always preaching in the same place, and to many of the same hearers, on Sundays. He was not nearly so much an itinerant as many of his contemporaries. He could not, like Whitefield, and Wesley, and Berridge, preach the same sermon over and over again, and yet feel that probably none of his hearers had heard it before.

Set for the defence of the gospel at Llangeitho every Sunday, and seeing every week the same faces looking up to him, he probably found it absolutely necessary to “bring forth new things as well as old,” and to be often exhorting many of his hearers not to stand still in first principles, but to “go on unto perfection.” But be the cause what it may, there is abundant evidence in the sermons of Rowlands that he never forgot the believers among his people, and generally contrived to say a good many things for their special benefit.

Here again, I venture to think, we have one more clue to his extraordinary usefulness. He “rightly divided the word of truth,” and gave to every man his portion. Most preachers of the gospel, T suspect, fail greatly in this matter. They either neglect the unconverted or the true Christians in their congregations. They either spend their strength in perpetually teaching elementary truths, or else they dwell exclusively on the privileges and duties of God’s children.

From this one-sided style of preaching Rowlands seems to have been singularly free. Even in the midst of the plainest addresses to the ungodly, he never loses the opportunity of making a general appeal to the godly. In a word, his ministry of God’s truth was thoroughly well balanced and well-proportioned; and this is just the ministry which we may expect the Holy Ghost will bless.

The manner and delivery of this great man, when he was in the act of preaching, require some special notice. Every sensible Christian knows well that voice and delivery have a great deal to say to the effectiveness of a speaker, and above all of one who speaks in the pulpit A sermon faultless both in doctrine and composition will often sound dull and tiresome, when tamely read by a clergyman with a heavy monotonous manner.

A sermon of little intrinsic merit, and containing perhaps not half-a-dozen ideas, will often pass muster as brilliant and elo-quent, when delivered by a lively speaker with a good voice. For want of good delivery some men make gold look like copper, while others, by the sheer force of a good delivery, make a few halfpence pass for gold. Truths divine seem really “mended” by the tongue of some, while they are marred and damaged by others.

There is deep wisdom and knowledge of human nature in the answer given by an ancient to one who asked what were the first qualifications of an orator “The first qualification,” he said, “is action; and the second is action; and the third is action.” The meaning of course was, that it was almost impossible to overrate the importance of manner and delivery.

The voice of Rowlands, according to tradition, was remarkably powerful. We may easily believe this, when we recollect that he used frequently to preach to thousands in the open air, and to make himself heard by all without difficulty. But we must not suppose that power was the only attribute of his vocal organ, and that he was nothing better than one who screamed, shouted, and bawled louder than other ministers.

There is universal testimony from all good judges who heard him, that his voice was singularly moving, affecting, and tender, and possessed a strange power of drawing forth the sympathies of his hearers. In this respect he seems to have resembled Baxter and Whitefield. Like Whitefield, too, his feelings never interfered with the exercise of his voice; and even when his affections moved him to tears in preaching, he was able to continue speaking with uninterrupted clearness.

It is a striking feature of the moving character of his voice that a remarkable revival of religion began at Llangeitho while Rowlands was reading the Litany of the Church of England. The singularly touching and melting manner in which he repeated the- words, “By thine agony and moody sweat, good Lord, deliver us,” so much affected the whole congregation, that almost all began to weep loudly, and an awakening of spiritual life commenced which extended throughout the neighbourhood.

Of the manner, demeanour, and action of Rowlands in the delivery of his sermons, mention is made by all who write of him. All describe them as being something so striking and remarkable, that no one could have an idea of them but an eyewitness. He seems to have combined in a most extraordinary degree solemnity and liveliness, dignity and familiarity, depth and fervour.

His singular plainness and directness made even the poorest feel at home when he preached; and yet he never degenerated into levity or buffoonery. His images and similes brought things home to his hearers with such graphic’ power that they could not help sometimes smiling. But he never made his Master’s business ridiculous by pulpit joking. If he did say things that made people smile occasionally, he far more often said things that made them weep.

The following sketch by the famous Welsh preacher, Christmas Evans, will probably give as good an idea as we can now obtain of Rowlands in the pulpit. It deserves the more attention, because it is the sketch of a Welshman, an eye-witness, a keen observer, a genuine admirer of his hero, and one who was himself in after-days a very extraordinary man

“Rowlands’ mode of preaching was peculiar to himself – inimitable. Methinks I see him now entering in his black gown through a little door from the outside to the pulpit, and making his appearance suddenly before the immense congregation. His countenance was in every sense adorned with majesty, and it bespoke the man of strong sense, eloquence, and authority. His forehead was high and prominent; his eye was quick, sharp, and penetrating; he had an aquiline or Roman nose, proportionable comely lips, projecting chin, and a sonorous, commanding, and well-toned voice.

“When he made his appearance in the pulpit, he frequently gave out, with a clear and audible voice, Psalm XXVII. 4 to be sung. Only one verse was sung before sermon, in those days notable for divine influences; but the whole congregation joined in singing it with great fervour. Then Rowlands would stand up, and read his text distinctly in the hearing of all.

The whole congregation were all ears and most attentive, as if they were on the point of hearing some evangelic and heavenly oracle, and the eyes of all the people were at the same time most intensely fixed upon him.

He had at the beginning of his discourse some stirring, striking idea, like a small box of ointment which he opened before the great one of his sermon, and it filed all the house with its heavenly perfume, as the odour of Mary’s alabaster box of ointment at Bethany; and the congregation being delightfully enlivened with the sweet odour, were prepared to look for more of it from one box after the other throughout the sermon.

“I will borrow another similitude in order to give some idea of his most energetic eloquence. It shall be taken from the trade of a blacksmith. The smith first puts the iron into the fire, and then blows the bellows softly, making some inquiries respecting the work to be done, while his eye all the time is fixed steadily on the process of heating the iron in the fire.

But as soon as he perceives it to be in a proper and pliable state, he carries it to the anvil, and brings the weighty hammer and sledge down on the metal, and in the midst of stunning noise and fiery sparks emitted from the glaring metal, he fashions and moulds it at his will.

“Thus Rowlands, having glanced at his notes as a matter of form, would go on with his discourse in a calm and deliberate manner, speaking with a free and audible voice; but he would gradually become warmed with his subject, and at length his voice became so elevated and authoritative, that it resounded through the whole chapel.

The effect on the people was wonderful; you could see nothing but smiles and tears running down the face of all. The first flame of heavenly devotion under the first division having subsided, he would again look on his scrap of notes, and begin the second time to melt and make the minds of the people supple, until he formed them again into the same heavenly temper. And thus he would do six or seven times in the same sermon.

“Rowlands’ voice, countenance, and appearance used to change exceedingly in the pulpit, and he seemed to be greatly excited; but there was nothing low or disagreeable in him—all was becoming, dignified, and excellent. There was such a vehement, invincible flame in his ministry, as effectually drove away the careless, worldly, dead spirit; and the people so awakened drew nigh, as it were, to the bright cloud—to Christ, to Moses, and Elias—eternity and its amazing realities rushing into their minds.

“There was very little, if any, inference or application at the end of Rowlands’ sermon, for he had been applying and enforcing the glorious truths of the gospel throughout the whole of his discourse. He would conclude with a very few striking and forcible remarks, which were most overwhelming and invincible; and then he would make a very sweet, short prayer, and utter the benediction.

Then he would make haste out of the pulpit through the little door. His exit was as sudden as his entrance. Rowlands was a star of the greatest magnitude that appeared the last century in the Principality; and perhaps there has not been his like in Wales since the days of the apostles.”

It seems almost needless to add other testimony to this graphic sketch, though it might easily be added. The late Mr. Jones of Creaton, who was no mean judge, and heard the greatest preachers in England and Wales, used to declare that “he never heard but one Rowlands.” The very first time he heard him, he was so struck with his manner of delivery, as well as his sermon, that it led him to a serious train of thought, which ultimately ended in his conversion.

Charles of Bala, himself a very eminent minister, said that there was a peculiar “ dignity and grandeur” in Rowlands’ ministry, “as well as profound thoughts, strength and melodiousness of voice, and clearness and animation in exhibiting the deep things of God.”

A Birmingham minister, who came accidentally to a place in Wales where Rowlands was preaching to an immense congregation in the open air, says: “I never witnessed such a scene before. The striking appearance of the preacher, and his zeal, animation, and fervour were beyond description. Rowlands’ countenance was most expressive; it glowed almost like an angel’s.”

After saying so much about the gifts and power of this great preacher, it is perhaps hardly fair to offer any specimens of his sermons. To say nothing of the fact that we only possess them in the form of translations, it must never be forgotten that true pulpit eloquence can rarely be expressed on paper.

Wise men know well that sermons, which are excellent to listen to, are just the sermons which do not “read” well. However, as I have hitherto generally given my readers some illustrations of the style of my last century heroes, they will perhaps be disappointed if I do not give them a few passages from Rowlands’.

My first specimen shall be taken from his sermon on the words, “All things work together for good to them that love God” (Rom. VIII. 28).

“Observe what he says. Make thou no exception, when he makes none. All!Remember he excepts nothing. Be thou confirmed in thy faith; give glory to God, and resolve, with Job, ‘Though he slay me, yet will I trust in him.’ The Almighty may seem for a season to be your enemy, in order that he may become your eternal friend. Oh! Believers, after all your tribulation and anguish, you must conclude with David, ‘It is good for me that I have been afflicted, that I might learn thy statutes.’

Under all your disquietudes you must exclaim, ‘O the depth of the riches both of the wisdom and knowledge of God! How unsearchable are his judgments, and his ways past finding out!’ His glory is seen when he works by means; it is more seen when he works without means; it is seen, above all when he works contrary to means. It was a great work to open the eyes of the blind; it was a greater still to do it by applying clay and spittle, things more likely, some think, to take away sight than to restore.

He sent a horror of great darkness on Abraham; when he was preparing to give him the best light. He touched the hollow of Jacob’s thigh, and lamed him, when he was going to bless him. He smote Paul with blindness, when he was intending to open the eyes of his mind. He refused the request of the woman of Canaan for a while, but afterwards she obtained her desire. See, therefore, that all the paths of the Lord are mercy, and that all things work together for good to them that love him.

“Even affliction is very useful and profitable to the godly. The prodigal son had no thought of returning to his father’s house till he had been humbled by adversity. Hagar was haughty under Abraham’s roof, and despised her mistress; but in the wilderness she was meek and lowly. Jonah sleeps on board ship, but in the whales belly he watches and prays.

Manasseh lived as a libertine at Jerusalem, and committed the most enormous crimes; but when he was bound in chains in the prison at Babylon his heart was turned to seek the Lord his God. Bodily pain and disease have been instrumental in rousing many to seek Christ, when those who were in high health have given themselves no concern about him. The ground, which is not rent and torn with the plough, bears nothing but thistles and thorns.

The vines will run wild, in process of time, if they be not pruned and trimmed. So would our wild hearts be overrun with filthy, poisonous weeds, if the true Vinedresser did not often check their growth by crosses and sanctified troubles. ‘It is good for a man that he bear the yoke in his youth.’ Our Saviour says, ‘Every branch that beareth fruit, my Father purgeth, that it may bring forth more fruit.’

There can be no gold. or silver finely wrought without being first purified with fire, and no elegant houses built with stones till the hammers have squared and smoothed them. So we can neither become vessels of honour in the house of our Father till we are melted in the furnace of affliction, nor lively stones in the walls of new Jerusalem till the hand of the Lord has beaten off our proud excrescences and tumours with his own hammers.

“He does not say that all things will but do, work together for good. The work is on the wheel, and every movement of the wheel is for your benefit. Not only the angels who encamp around you, or the saints who continually pray for you, but even your enemies, the old dragon and his angels, are engaged in this matter. It is true; this is not their design. No.

They think they are carrying on their own work of destroying you, as it is said of the Assyrian whom the Lord sent to punish a hypocritical nation, ‘Howbeit, he meaneth not so;’ yet it was God’s work that he was carrying on, though he did not intend to do so. All the events that take place in the world carry on the same work—the glory of the Father and the salvation of his children.

Every illness and infirmity that may seize you, every loss you may meet with, every reproach you may endure, every shame that may colour your faces, every sorrow in your hearts, every agony and pain in your flesh, every aching in your bones, are for your good. Every change in your condition – your fine weather and your rough weather, your sunny weather and your cloudy weather, your ebbing and your flowing, your liberty and your imprisonment, all turn out for good.

Oh, Christians, see what a harvest of blessings ripens from this text! The Lord is at work; all creation is at work; men and angels, friends and foes, all are busy, working together for good. Oh, dear Lord Jesus, what hast thou seen in us that thou shouldst order things so wondrously for us, and make all things—allthings to work together for our good?”

My second specimen shall be taken from his sermon on Rev. III. 20

“Oh, how barren and unfruitful is the soul of man, until the word descends like rain upon it, and it is watered with the dew of heaven! But when a few drops have entered and made it supple, what a rich harvest of graces do they produce! Is the heart so full of malice that the most suppliant knee can expect no pardon? Is it as hard to be pacified and calmed as the roaring sea when agitated by a furious tempest?

Is it a covetous heart; so covetous that no scene of distress can soften it into sympathy, and no object of wretchedness extort a penny from its gripe? Is it a wanton and adulterous heart, which may as soon be satisfied as the sea can be filled with gold? Be it so. But when the word shall ‘drop on it as the rain, and distil as the dew,’ behold, in an instant the flint is turned into flesh, the tumultuous sea is hushed into a calm, and the mountains of Gilboa are clothed with herbs and flowers, where before not a green blade was to be seen!

See the mighty change! It converts Zaccheus, the hard-hearted publican and rapacious tax-gatherer, into a restorer of what he had unjustly gotten, and a merciful reliever of the needy. It tames the furious persecuting Saul, and makes him gentle as a lamb. It clothes Ahab with sackcloth and ashes.

It reduces Felix to such anguish of mind that he trembles like an aspen leaf. It disposes Peter to leave his nets, and makes him to catch thousands of souls at one draught in the net of the gospel. Behold, the world is converted to the faith, not by the magicians of Egypt, but by the outcasts of Judea!”

The last specimen that I will give is from his sermon on Heb. I. 9:

“Christ took our nature upon him that he might sympathize with us. Almost every creature is tender toward its own kind, however ferocious to others. The bear will not be deprived of her whelps without resistance: she will tear the spoiler to pieces if she can. But how great must be the jealousy of the Lord Jesus for his people I He will not lose any of them. He has taken them as members of himself, and as such watches over them with fondest care. How much will a man do for one of his members before he suffers it to be cut off?

Think not, 0 man, that thou wouldst do more for thy members than the Son of God. To think so would be blasphemy, for the pre-eminence in all things belongs to him. Yea, he is acquainted with all thy temptations, because he was in all things tempted as thou art. Art thou tempted to deny God? So was he. Art thou tempted to kill thyself? So was he. Art thou tempted by the vanities of the world?

So was he. Art thou tempted to idolatry? So was he; yea, even to worship the devil. He was tempted from the manger to the cross. He was a man of sorrows and acquainted with grief The Head in heaven is sympathizing with the feet that are pinched and pressed on earth, and says, ‘Saul, Saul, why persecutest thou me?”’

I should find no difficulty in adding to these extracts, if the space at my command did not forbid me. Feeble and unsatisfactory, as they undoubtedly are, in the form of a translation, they will perhaps give my readers some idea of what Rowlands was in the pulpit, so far as concerns the working of his mind. Of his manner and delivery, of course, they cannot give the least idea. It would be easy to fill pages with short, epigrammatic, proverbial sayings culled from his sermons, of which there is a rich abundance in many passages.

But enough, perhaps, has been brought forward to give a general impression of the preaching that did such wonders at LIangeitho. Those who want to know more of it should try to get hold of the little volume of translated sermons from which my extracts have been made. Faintly and inadequately as it represents the great Welsh preacher, it is still a volume worth having, and one that ought to be better known than it is. Scores of books are reprinted in the present day, which are not half so valuable as Rowlands’ eight sermons.

The inner life and private character of the great Welsh preacher would form a deeply interesting subject, no doubt, if we knew more about them. But the utter absence of all materials except a few scattered anecdotes leaves us very much in the dark. Unless the memoirs of great men are written by relatives, neighbours, or contemporaries, it stands to reason that we shall know little of anything but their public conduct and doings.

This applies eminently to Daniel Rowlands. He had no Boswell near him to chronicle the details of his long and laborious life, and to present him to us as he appeared at home. The consequence is, that a vast quantity of interesting matter, which the Church of Christ would like to know, lies buried with him in his grave.

One thing, at any rate, is very certain. His private life was as holy, blameless, and consistent, as the life of a Christian can be. Some fifteen years ago, the Quarterly Review contained an article insinuating that he was addicted to drunkenness, which called forth an indignant and complete refutation from many competent witnesses in South Wales, and specially from the neighbourhood of Llangeitho. – That such charges should be made against good men need never surprise us.

Slander and lying are the devil’s favourite weapons, when he wants to injure the mightiest assailants of his kingdom. Satan is pre-eminently “a liar.” Bunyan, Whitefield, and Wesley had to drink of the same bitter cup as Rowlands. But that the charge against Rowlands was a mere groundless, malicious falsehood, was abundantly proved by Mr. Griffith, the vicar of Aberdare, in a reply to the article of the Quarterly Review,printed at Cardiff.

We need not be reminded, if we read our Bibles, who it was of whom the wicked Jews said, “Behold a man gluttonous, and a winebibber, a friend of publicans and sinners” (Matt. XI. 19). If the children of this world cannot prevent the gospel being preached, they try to blacken the character of the preacher. What saith the Scripture?”

The disciple is not above his master, nor the servant above his lord. It is enough for the disciple that he be as his master, and the servant as his lord. If they have called the Master of the house Beelzebub, how much more shall they call them of his household?” (Matt X. 24, 25).

The only light that we can throw on the character and private habits of Rowlands is derived from the few anecdotes which still survive about him. I shall, therefore, conclude my account of him by presenting them to my readers without note or comment.

One leading feature in Rowlands’ character was his humility.Like every eminent servant of God of whom much is known, he had a deep and abiding sense of his own sinfulness, weakness, and corruption, and his constant need of God’s grace. On seeing a vast concourse of people coming to hear him, he would frequently exclaim: “Oh, may the Lord have mercy on me, and help me, a poor worm, sinful dust and ashes.”

When a backslider was pointed out to him, who had once been one of his followers, he said: “It is to be feared indeed that he is one of my disciples; for had he been one of my Lord’s disciples, he would not have been in such a state of sin and rebellion.” He often used to say, during his latter days, that there were four lessons which he had laboured to learn throughout the whole course of his religious life, and yet that he was but a dull scholar even in his old age.

These lessons were the following.. (I.) To repent without despairing; (2.) To believe without being presumptuous; (3.) To rejoice without falling into levity (4.) To be angry without sinning. He used also often to say, that a self-righteous legal spirit in man was like his shirt, a garment which he puts on first, and puts off last.

A habit of praying muchwas another leading characteristic of Rowlands. It is said that he used often to go to the top of Aeron Hills, and there pour out his heart before God in the most tender and earnest manner for the salvation of the numerous inhabitants of the country which lay around him. “He lived,” says Morgan, “in the spirit of prayer, and hence his extraordinary success.

On one occasion having engaged to preach at a certain church, which stood on an eminence, he had to cross a valley in sight of the people, who were waiting for him in the churchyard. They saw him descend into the bottom of the valley, but then lost sight of him for some time. At last, as he did not come up by the time they expected, and service-time had arrived, some of them went down the hill in search of him. They discovered him, at length, on his knees in a retired spot a little out of the road.

He got up when he saw them, and went with them, expressing sorrow for the delay; but he added, ‘I had a delightful opportunity below.’ The sermon which followed was most extraordinary in power and effect.”

Diligence was another distinguishing feature in the character of Rowlands. He was continually improving his mind, by reading, meditation, and study. He used to be up and reading as early as four o’clock in the morning; and he took immense pains in the preparation of his sermons. Morgan says, “Every part of God’s Word, at length, became quite familiar to him.

He could tell chapter and verse of any text or passage of Scripture that was mentioned to him. Indeed the word of God dwelt richly in him. He had, moreover, a most retentive memory, and when preaching, could repeat the texts referred to, off-hand, most easily and appropriately.”

Self-denial was another leading feature of Rowlands’ character. He was all his life a very poor man; but he was always a contented one, and lived in the simplest way. Twice he refused the offer of good livings—one in North Wales, and the other in South Wales—and preferred to remain a dependent curate with his flock at Llangeitho. The offer in one case came from the excellent John Thornton.

When he heard that Rowlands had refused it, and ascertained his reasons, he wrote to his son, saying, “I had a high opinion of your father before, but now I have a still higher opinion of him, though he declines my offer. The reasons he assigns are highly creditable to him. It is not a usual thing with me to allow other people to go to my pocket; but tell your father that he is fully welcome to do so whenever he pleases.”

The residence of the great Welsh evangelist throughout life was nothing but a small cottage possessing no great accommodation. His journeys, when he went about preaching, were made on horseback, until at last a small carriage was left him as a legacy in his old age.

He was content, when journeying in his Master’s service, with very poor fare and very indifferent lodgings, he says himself, “We used to travel over hills and mountains, on our little nags, without anything to eat but the bread and cheese we carried in our pockets, and without anything to drink but water from the springs. If we had a little buttermilk in some cottages we thought it a great thing.

But now men must have tea, and some, too, must have brandy!’ Never did man seem so thoroughly to realize the primitive and apostolic rule of life. Having food and raiment, let us be therewith content.”

Courage was another prominent feature in Rowlands’ character. He was often fiercely persecuted when he went about preaching, and even his life was sometimes in danger. Once, when he was preaching at Aberystwith, a man swore in a dreadful manner that he would shoot him immediately. He aimed his gun, and pulled the trigger, but it would not go off.

On another occasion his enemies actually placed gunpowder under the place where he was about to stand when preaching, and laid a train to a distant point, so that at a given time they might apply a match, and blow up the preacher and congregation. However, before the time arrived, a good man providentially discovered the whole plot, and brought it to nothing.

On other occasions riotous mobs were assembled, stones were thrown, drums beaten, and every effort made to prevent} the sermon being heard. None of these things ever seems to have deterred Rowlands for a moment. As long as he had strength to work he went on with his Master’s business, unmoved by opposition and persecution.

Like Colonel Gardiner, he “feared God, and beside him he feared nothing.” He had given himself to the work of preaching the gospel, and from this work he allowed neither clergy nor laity, bishops nor gentry, rich nor poor, to keep him back.

Fervent and deep feelingwas the last characteristic, which I mark in Rowlands. He never did anything by halves. Whether preaching or praying, whether in church or in the open air, he seems to have done all he did with heart and soul, and mind and strength. “He possessed as much animal spirits,” says one witness, “as were sufficient for half a dozen men.”

This energy seems to have had an inspiring effect about it, and to have swept everything before it like a fire. One who went to hear him every month from Carnarvonshire, gives a striking account of his singular fervour when Rowlands was preaching on John III. I6. He says, “He dwelt with such overwhelming, extraordinary thoughts on the love of God, and the vastness of his gift to man, that I was swallowed up in amazement. I did not know that my feet were on the ground; yea, I had no idea where I was, whether on earth or in heaven.

But presently he cried out with a most powerful voice, ‘Praised be God for keeping the Jews in ignorance respecting the greatness of the Person in their hands! Had they known who he was, they would never have presumed to touch him, much less to drive nails through his blessed hands and feet, and to put a crown of thorns on his holy head.

For had they known, they would not have crucified the Lord of glory. I will wind up this account of Rowlands by mentioning a little incident which the famous Rowland Hill often spoke of in his latter days. He was attending a meeting of Methodist ministers in Wales in one of his visits, when a man, nearly a hundred years old, got up from a corner of the room and addressed the meeting in the following words:-

“Brethren, let me tell you this: I have heard Daniel Rowlands preach, and I heard him once say, Except your con-sciences be cleansed by the blood of Christ, you must all perish in the eternal fires.”

Rowlands, at that tune, had been dead more than a quarter of a century. Yet, even at that interval, “though dead he spoke.” It is a faithful saying, and worthy of all remembrance, that the ministry, which exalts Christ, crucified most, is the ministry, which produces most lasting effects. Never, perhaps, did any preacher exalt Christ more than Rowlands did, and never did preacher leave behind him such deep and abiding marks in the isolated corner of the world where he laboured a hundred years ago.

For further research:

Daniel Rowland Wikipedia

Daniel Rowland