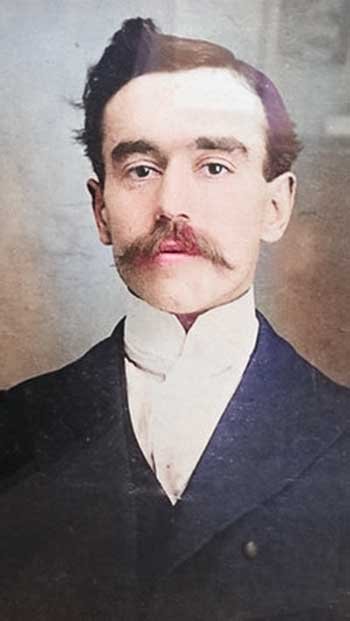

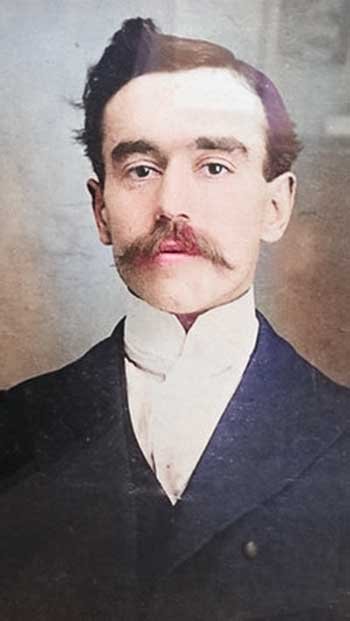

Charles Parham

1903-1905 Galena and Baxter Springs Revivals

Charles Parham

Introduction: The Crucible of the Tri-State Mining District

In the autumn of 1903, the burgeoning lead and zinc mining town of Galena, Kansas, located in the heart of the Tri-State Mining District, became the unlikely stage for a series of religious revivals that would fundamentally alter the course of twentieth-century Christianity.1 The socio-economic landscape of Galena was defined by the arduous and often perilous life of its working-class population, a community of miners and labourers for whom hardship was a daily reality.2

This environment, characterized by a tangible need for hope and a populist suspicion of established institutions, proved to be exceptionally fertile ground for a religious message predicated on direct divine intervention, empowerment, and physical restoration.1

The figure who arrived in this setting was Charles Fox Parham, an itinerant preacher whose ministry was, by all accounts, at its lowest point. Two years prior, in Topeka, Parham and a small group of students at his Bethel Bible School had formulated a radical new doctrine: that the baptism in the Holy Spirit was necessarily evidenced by the supernatural ability to speak in unlearned foreign languages.4

This 1901 event, while later hailed as the genesis of modern Pentecostalism, was an immediate and public failure. Parham’s movement dissolved amidst scathing media ridicule, the defection of his students, and the profound personal tragedy of his young son’s death.6 By 1903, Charles Parham was a leader with a revolutionary theology but no discernible movement to lead.

This report posits a central thesis: that the revivals held in Galena and subsequently in Baxter Springs between October 1903 and 1905 were not merely successful evangelistic meetings. They were the critical, transformative events that rescued Parham’s “Apostolic Faith” movement from the brink of historical obscurity.

These revivals provided the movement with the essential human and material resources it had previously lacked, validated its claims through tangible and widely reported supernatural phenomena, and set it on a direct and causal trajectory toward the globally significant Azusa Street Revival of 1906.

By examining the antecedents, content, manifestations, reception, and lasting legacies of these Kansas revivals, this analysis will demonstrate that it was in the gritty mining towns of southeastern Kansas, not the quiet Bible school in Topeka, that Pentecostalism was forged into a viable and expansive religious force.

Section I: Antecedents to the Kansas Revivals

To comprehend the explosive impact of the Galena revival, it is essential to first understand the theological and personal journey of its architect, Charles Parham, and the doctrinal framework he brought to the small mining town. His “Apostolic Faith” message was not an ex nihilo creation but a potent synthesis of the most radical religious currents of his time, refined through personal suffering and tested in the crucible of public failure.

The Making of a “Projector”: Parham’s Theological Formation

Charles Parham’s early life was a tapestry of physical suffering and spiritual seeking that profoundly shaped his later ministry. Born in 1873, he was plagued from infancy by a series of debilitating illnesses, including encephalitis and recurring, agonizing bouts of rheumatic fever.8

These experiences instilled in him a deep-seated preoccupation with physical affliction and a fervent belief in the possibility of divine healing. After a profound healing experience in 1891, during which he believed God cured him of rheumatic fever and a club foot, divine healing became a non-negotiable cornerstone of his theology.8

Parham’s formal ministerial career began within the Methodist Episcopal Church, where he enrolled at Southwestern Kansas College in 1890 and later served as a supply pastor.4 However, his independent spirit and desire for what he termed “direct inspiration” soon brought him into conflict with the denominational hierarchy.7

By 1895, he had permanently severed ties with Methodism and all “sectarian churchism,” embarking on a career as an independent evangelist.5 This break plunged him into the turbulent and dynamic world of the late nineteenth-century Holiness movement. It was within the most radical wing of this movement, particularly strong in the American Plains, that Parham’s theology took its definitive shape.5

The Holiness movement, an offshoot of Wesleyanism, stressed a “second blessing” of entire sanctification subsequent to conversion, but its more extreme adherents were pushing for a “third experience”—a “baptism with the Holy Ghost and fire” that would restore the power of the apostolic church.6

Parham proved to be a masterful synthesizer of the ideas circulating within this milieu. He was not so much an inventor as a brilliant integrator who combined disparate elements into a new, cohesive whole. He visited and drew inspiration from two of the most significant figures in the radical restorationist movement.

From John Alexander Dowie’s healing homes in Chicago, he adopted a model for a centralized ministry focused on faith healing, which he replicated in 1898 with the opening of his Beth-el Healing Home in Topeka.10 More consequentially, he was influenced by the work of Frank W. Sandford in Shiloh, Maine.7

From Sandford, Parham borrowed the model for his own faith-based Bible school and, crucially, absorbed the eschatological belief that God would restore the New Testament gift of xenolalia—the ability to speak in known, unlearned human languages—to empower a final, worldwide evangelistic crusade before the imminent return of Christ.4

Parham’s unique contribution was to take these pre-existing concepts—divine healing from Dowie, the communal school model and missionary tongues from Sandford, and the Holiness concept of a third blessing—and fuse them together.

He elevated the gift of tongues from an occasional manifestation, as Sandford viewed it, to the indispensable, definitive sign of receiving this end-times spiritual baptism, thereby creating a distinct and powerful theological package.4

The Topeka Postulate (1901): A Doctrine in Search of a Movement

In the fall of 1900, Parham opened the Bethel Bible School in a grand, turreted mansion in Topeka known locally as “Stone’s Folly”.6 It was here that his synthesized theology was put to the test. The school operated on a faith basis, with the Bible as its only textbook and the Holy Spirit as its purported teacher.7

In late December 1900, Parham assigned his students to systematically study the Book of Acts to determine the biblical evidence for the baptism of the Holy Spirit.10 Upon his return, the students reported a unanimous conclusion: the indisputable sign was speaking in other tongues.10

On the evening of January 1, 1901, during a Watch Night service, a student named Agnes Ozman asked Parham to lay hands on her that she might receive the Holy Spirit with the evidence of tongues. According to the accounts, she began to speak in a language believed to be Chinese, unable to speak English for three days.1

In the days that followed, Parham and about half of the forty students also reported receiving the experience, speaking in a variety of languages including Swedish, Russian, and Italian.1 This event marked the birth of Parham’s most significant and enduring theological contribution: the doctrine of initial physical evidence.

While others in Christian history had spoken in tongues, Parham was the first to articulate and systematize the belief that glossolalia was the necessary and universal initial sign that a believer had received the baptism in the Holy Spirit.5 This doctrine would become the theological hallmark of the global Pentecostal movement.

The immediate aftermath of the Topeka outpouring, however, was not revival but collapse. The initial flurry of interest from the local press quickly soured into skepticism and outright ridicule, with reporters dubbing the school the “Tower of Babel” and describing the tongues as mere “gibberish”.7

The movement’s central claim—that believers were being equipped with actual foreign languages for immediate missionary service—was an abstract, future-oriented promise that proved impossible to verify. When early Pentecostal missionaries like A. G. Garr later arrived in fields like India, they discovered they could not, in fact, speak Hindi supernaturally and had to resort to interpreters.6

This failure to produce a tangible, verifiable outcome rendered the movement vulnerable to mockery. Lacking public support and credibility, and with many of his former students denouncing him as a fake, Parham’s ministry dissolved by April 1901.7

For the next two and a half years, he languished in relative obscurity, a period of struggle during which he wrote his first book, Kol Kare Bomidbar: A Voice Crying in the Wilderness.20 The Topeka experiment had produced a doctrine, but it had failed to produce a sustainable movement. It would require a different kind of validation—one more immediate, tangible, and personally beneficial to its audience—to gain public traction.

Section II: The Galena Revival (October 1903 – January 1904): A Movement Catches Fire

After more than two years of failure and obscurity, Charles Parham’s fortunes dramatically reversed in the fall of 1903. The revival that erupted in Galena, Kansas, was not a continuation of the Topeka experiment but a fundamental recalibration of it. It was here that Parham’s Apostolic Faith message, grounded in the immediate and tangible promise of divine healing, finally found a receptive audience, transforming his fledgling doctrine into a mass movement.

The Spark: The Healing of Mary Arthur

The direct catalyst for the Galena revival was a single, dramatic act of divine healing. The chain of events began not in Galena, but in El Dorado Springs, Missouri, a popular health resort where people flocked to “take the water cure”.10

While preaching there, Parham encountered Mary A. Arthur, the wife of a prominent Galena citizen.7 Arthur was a chronic invalid, suffering for fourteen years from a litany of debilitating ailments, including dyspepsia, paralysis of the bowels, and, most distressingly, a degenerative condition of the optic nerve that left her nearly blind and in constant pain.21

In her own detailed testimony, Arthur recounted years of seeking relief from prominent oculists and various medical and alternative therapies, all of which ended in “sudden new disappointment”.21 Her search for spiritual healing was equally frustrating; her own pastor repeatedly deferred her requests for prayer, citing the busyness of church reports and holiday addresses.21

It was in this state of desperation that she heard Parham’s announcement in El Dorado Springs: “If there are any here who are seeking God for salvation or healing of their bodies, come to my house tomorrow morning”.21 On August 17, 1903, Parham prayed for her, and she claimed a complete and instantaneous healing.22

Overjoyed and convinced of the authenticity of Parham’s message, Mary Arthur and her husband invited him to come to Galena and preach in their home.7 This personal invitation, backed by the credibility of a well-known local family and a verifiable, dramatic healing, provided the entry point and initial legitimacy that Parham’s movement had desperately needed.

Anatomy of the Revival: From Parlor to Public Square

The revival began in the fall of 1903 in the “large and commodious” living room of the Arthur home at 311 Galena Street.23 The response was immediate and overwhelming. The crowds of “hungry people” quickly proved too large for the house to accommodate.23 At one point, the press of people trying to get into the house became so great that the front porch collapsed under their weight, miraculously without injuring anyone.24

This explosive growth necessitated a series of venue changes that tracked the revival’s escalating scale. From the Arthur home, the meetings moved to a large tent erected on an adjacent vacant lot, where they continued until after Thanksgiving.23 As the cold Kansas winter approached, the revival relocated again, this time to the “Grand Leader” building, an immense double storeroom on Main Street capable of holding over a thousand people.1

Even this massive space proved insufficient. Two meetings were held each day, and according to Sarah Parham, “the doors were many times thrown wide open as the crowds overflowed into the street”.23

The revival, which ran intensively from October 1903 to late January 1904, captivated the entire region.1 While claims that the entire city of 80,000 was moved are likely an exaggeration of the town’s actual population, they speak to the perception of the revival’s pervasive influence.23

The meetings drew a notable cross-section of society. Newspaper reports from the time observed the levelling effect of the gatherings, where “the man of prominence and position clasps hands with the uneducated son of toil” and “women who have formerly lived for society and gaiety kneel beside some fallen sister”.25

The presence of “business and professional men and families” and other prominent citizens alongside the miners and working-class families of Galena was a key feature of its success and a stark contrast to the small, isolated group of students at Topeka.1

The “Full Gospel” Proclaimed: A Populist Theology

In the charged atmosphere of the Galena meetings, Parham preached what he termed the “Full Gospel” or the “Apostolic Faith”.20 This message was a comprehensive theological system built upon the foundation of the Holiness movement but with distinctive additions that set it apart.

The core tenets included: personal conversion (salvation); Wesleyan sanctification as a definite “second work of grace” 5; divine healing as a provision in the atonement and a Christian’s birthright, which necessitated the rejection of all medicine and doctors 10; and the climactic experience of the baptism of the Holy Spirit, invariably accompanied by the initial physical evidence of speaking in other tongues.4

A crucial element of Parham’s preaching, and one that resonated deeply in the populist environment of a Kansas mining town, was his relentless and “scathing attacks on the professional clergy”.1 He positioned himself as a champion of “the people” against an entrenched religious establishment.

He accused local ministers of being hirelings more concerned with salaries and denominational upkeep than with the spiritual and physical needs of their flocks, arguing that their institutionalism was the reason people were turning away from the churches.1

This anti-establishment rhetoric created a powerful narrative that cast his Apostolic Faith movement as a genuine, grassroots restoration of primitive Christianity, in contrast to the cold formalism he attributed to the mainstream denominations.8

Alongside these central themes, Parham also taught his more idiosyncratic and controversial doctrines. He advocated for water baptism by single immersion in the name of Jesus Christ, a departure from the traditional Trinitarian formula that prefigured later “Oneness” Pentecostal theology.23

He also preached annihilationism, the belief that the souls of the wicked are ultimately destroyed rather than subjected to eternal conscious torment, and Anglo-Israelism, the fringe theory that the Anglo-Saxon peoples were the literal descendants of the ten lost tribes of Israel.14

While these latter doctrines would eventually contribute to his marginalization within the broader Pentecostal movement, they were an integral part of the theological package that captivated Galena in 1903.

“Signs and Wonders”: Documented Supernatural Manifestations

The Galena revival was defined by an atmosphere of constant and spectacular supernaturalism. “Miracles and wonders seemed to be a constant occurrence,” recalled one prominent convert.2 These manifestations served as the primary validation of Parham’s message.

The most prominent and persuasive feature was divine healing. The success of the revival was built on the premise that God was still healing the sick just as He had in the New Testament. Reports from the period claimed staggering numbers, with contemporary accounts citing “hundreds” and later summaries claiming as many as “a thousand” people were healed.7

The Joplin Daily News Herald reported that “many of the most prominent people in town have professed to having been healed of blindness, cancer, rheumatism and other diseases”.26 The tangible, life-altering nature of these healings, beginning with Mary Arthur, was the engine that drove the revival’s growth.

It shifted the primary evidence of God’s power from the abstract and unverifiable promise of missionary tongues to the immediate and personally beneficial reality of physical restoration. This was a message that resonated powerfully with a community well-acquainted with physical suffering.

While healing was the main draw, glossolalia remained a central component of the experience. Hundreds of attendees were reported to have been “filled with the baptism of the Holy Spirit”.23 These were not merely ecstatic utterances; they were often perceived as intelligible languages, lending them an air of profound supernatural validation.

Mary Arthur provided a compelling eyewitness account of a spiritual song that emerged during a tent meeting: “the Spirit came in heavenly song, then the interpretation in English… Two men from St. Louis visiting a friend came to the meeting and heard the anthem by the Spirit and said it was sung in the most perfect Latin tongue, and perfectly translated in English.

They said that their church choir had tried to learn it for a month, then finally gave it up as too difficult”.21 Such testimonies, particularly from educated outsiders, bolstered the credibility of the phenomena and reinforced the belief that God was supernaturally restoring the gifts of the apostolic age.

The combination of dramatic healings and supernatural linguistics resulted in a massive wave of conversions. Sources consistently report that “hundreds” were converted, with specific figures of 800 or 875 being cited by the end of the revival in January 1904.1 These converts formed the nucleus of the revitalized Apostolic Faith movement.

Case Study of a Key Convert: The Transformation of Howard A. Goss

The power of the Galena revival is perhaps best illustrated through the story of one of its most significant converts, Howard A. Goss. When the revival began, Goss was a high school student and a self-described “practicing infidel” who was skeptical about the existence of God.2

His high school teacher, Mary Arthur’s sister, challenged him to attend the meetings.2 Initially drawn by curiosity, Goss was profoundly affected by what he witnessed. He later stated unequivocally that he owed his conversion to Christianity to hearing people speak in other tongues.2 The supernatural phenomena he observed convinced him “that somewhere there existed a being that men called God”.2

Goss’s transformation from skeptic to believer was total. On one of the coldest days of the winter, he was one of approximately 100 new converts whom Parham baptized by immersion in the frigid waters of the nearby Spring River.2

This act symbolized his full entry into the movement. Goss would go on to become one of Parham’s key co-workers, a foundational figure in the creation of the Assemblies of God in 1914, and later the first General Superintendent of the United Pentecostal Church International.29

His journey from the high school classrooms of Galena to the highest echelons of Pentecostal leadership demonstrates the revival’s most crucial function: it did not just win converts; it forged the future leaders who would carry the movement far beyond the borders of Kansas.

Section III: The Baxter Springs Revival and Consolidation

The explosive evangelistic success in Galena provided Charles Parham with a large, dedicated following and a renewed sense of purpose. The next phase of his work, centered in the nearby town of Baxter Springs, represented a strategic shift from pure revivalism to the consolidation and institutionalization of his Apostolic Faith movement.

While the meetings in Baxter Springs were less spectacular than those in Galena, their long-term significance was arguably just as great, as it was here that the movement established its first permanent headquarters.

Expanding the Frontier: The Baxter Springs Meetings

Building on the momentum from Galena, Parham began taking his message to surrounding communities in 1904. One of the first and most important of these new frontiers was Baxter Springs, a town located approximately ten miles to the west.30

The revival meetings held in Baxter Springs were smaller in scale than the massive gatherings that had overwhelmed Galena. Accounts from the period note that the crowds were “not as great,” reflecting a more modest public response.30

Despite the smaller attendance, the meetings were deemed a “genuine revival,” successfully planting the Apostolic Faith message in a new community and winning numerous converts.30 Parham’s involvement with Baxter Springs was not a one-time event but an ongoing commitment.

He conducted his first formal revival campaign there in 1905 and returned later that year to fulfil planned appointments after his initial and highly successful evangelistic tours through Texas.31 Baxter Springs thus became a regular and important stop on his expanding ministry circuit.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of the Galena and Baxter Springs Revivals

The distinct roles played by Galena and Baxter Springs in the development of the Apostolic Faith movement can be summarized as a transition from catalytic event to strategic center. The following table provides a comparative analysis of the two locations.

| Feature | Galena Revival (Oct 1903 – Jan 1904) | Baxter Springs Meetings (1904-1905 onwards) |

| Timeline | Intensive, four-month period of continuous meetings 1 | Intermittent campaigns and appointments over a longer period 31 |

| Scale/Attendance | Massive; thousands attending daily; overflow crowds into the streets 1 | Smaller; “not as great” crowds, but still considered a genuine revival 30 |

| Primary Function | Public-facing mass evangelism; the catalyst that ignited the movement 1 | Consolidation of gains; establishment of a permanent base of operations 13 |

| Key Venues | Progressively larger spaces: private home, large tent, massive warehouse 23 | Unspecified meeting locations initially; later, the converted brewery building 30 |

| Primary Outcome | Mass conversions and healings; creation of a dedicated evangelistic workforce 7 | Establishment of the permanent international headquarters for the movement 13 |

Establishing a Headquarters: From Brewery to Base of Operations

Parham’s decision to establish his permanent headquarters in Baxter Springs was a deliberate and strategic move that signalled his transition from an itinerant evangelist to the head of an organized religious movement. He was reportedly “so impressed with the town” that he chose it as the anchor for his entire Apostolic Faith enterprise.30

This choice was likely influenced by several factors. A smaller town like Baxter Springs offered a quieter, more controllable environment than Galena, where his revival had generated intense media scrutiny and significant opposition from the local clergy.1 By establishing his base away from this contentious atmosphere, Parham could consolidate his authority and build his organization with less external interference.

The physical embodiment of this institutionalization was his purchase of the old “Zellekin” brewery, a substantial brick building in Baxter Springs.30 Parham transformed this secular structure into a multi-purpose facility that became the nerve center of the movement. It served as a home for his family, the official headquarters for the Apostolic Faith Movement, and, most importantly, the home of the printing press for his periodical, The Apostolic Faith.30

The establishment of this headquarters was a pivotal development. It provided the movement with a fixed geographical and institutional center, lending it a sense of permanence and stability it had previously lacked. The printing press was a particularly crucial asset.

It allowed Parham to mass-produce and distribute his newspaper, which documented the teachings and testimonies of the movement and became the primary vehicle for spreading his message across the United States.33

From this base in Baxter Springs, Parham could coordinate the activities of the evangelistic “bands” that had been formed out of the Galena revival and manage the growth of a movement that was rapidly expanding beyond the borders of Kansas.7

Section IV: Reception and Reaction

The Galena revival did not occur in a vacuum. Its spectacular growth and radical claims provoked strong reactions from the public, the press, and the established religious community. The reception was a complex mixture of enthusiastic support, journalistic curiosity, and fierce opposition, which collectively shaped the public narrative of the nascent Pentecostal movement and arguably reinforced the identity of its followers.

The Press: A Double-Edged Sword

The media played a crucial and complex role in the revival’s trajectory. Initially, positive press coverage was a significant factor in its success. Favorable reports of miraculous healings and mass conversions were published in newspapers as far away as Cincinnati, lending an air of credibility to the meetings and attracting thousands of curious attendees.6

The Joplin Daily Globe ran an early story highlighting the supernatural claims, stating, “The wicked are being forgiven and blessed, the blind are made to see, cripples throw away their crutches and walk as they never walked before”.1 This kind of publicity was instrumental in transforming a local gathering into a regional phenomenon.

However, this supportive tone was short-lived. The same newspapers that reported on the miracles soon began to publish critical and satirical articles. The day after its positive report, the Joplin Daily Globe ran a piece that poked fun at the claims of speaking in tongues, questioning “just what business a bona fide Holy Spirit could possibly have with some of the foreign languages”.1

The press also began to scrutinize Parham’s leadership, highlighting his “scathing attacks on the professional clergy” and questioning his faith-based fundraising methods. One report noted that while Parham did not take collections, he would invite the audience to shake his right hand and would not object if they dropped money into his left, a practice that reportedly netted him a “considerable amount of money”.1

This dualistic coverage demonstrates the media’s role as both an amplifier and a critic, simultaneously spreading news of the revival while attempting to frame it as a fanatical and potentially fraudulent enterprise.

The Pulpit and the Public: Clerical Opposition and Doctrinal Disputes

The most organized and vehement opposition to Parham came from the established religious leaders of Galena, whom he had directly and repeatedly attacked from his pulpit. His anti-clergy rhetoric, a key element of his populist appeal, provoked a swift and sustained backlash.1 In response to the Apostolic Faith revival’s success, both the local Methodist and Baptist churches launched competing revival meetings of their own.

The Methodist minister, Reverend Frank W. Otto, was described as being in “open conflict” with Parham, and newspaper reports deliberately contrasted Otto’s “clear, logical” sermons with Parham’s perceived “fanaticism and rant”.1 The themes of these competing services, such as a sermon on “an endless hell,” were clearly intended as direct theological rebuttals to Parham’s doctrine of annihilationism.1

The most systematic critique came from C.W. Harvey, a prominent Quaker and respected citizen, who published a series of editorials in the Galena Evening Times. Harvey methodically deconstructed Parham’s teachings, comparing his claims of faith healing to those of “John Alexander Dowie, Mormonism, Christian Science… Hypnotism, Spiritual Magnetism, and Spiritualism” and dismissing them as no more valid than patent medicine testimonials.1

He argued that speaking in tongues was a minor gift that had ceased to be important in the early church and expressed concern that converts were being swayed by a “new hobby or romance in doctrine” without serious examination.1 Harvey concluded by branding Parham “the chief operator in speculation and fables in our city” and condemning his attacks on local pastors, whom Parham had allegedly called “hypocrites,” “Pharisees,” and “deceivers of the people”.1

Parham’s public credibility was further damaged by a conflict with Sara C. Scovell, the leader of the First Spiritualist Church in Galena. After Scovell publicly challenged Parham’s claims, she suffered a health crisis. Parham announced from the rostrum that God had stricken her dumb for her opposition. When Scovell recovered and publicly refuted his pronouncement, it made Parham appear foolish and presumptuous.1

This clerical and public opposition, while aimed at undermining the revival, likely had an unintended effect. For Parham’s followers, who had embraced a message of “comeoutism” and separation from what they saw as dead, formal denominations, this persecution would have served as powerful confirmation of their beliefs.12

The vocal opposition from pastors and the critical press coverage validated Parham’s narrative that they were part of a true apostolic restoration standing against a fallen religious establishment. The resistance they faced was not a sign of error but a badge of honor, a mark of authenticity that reinforced group cohesion and deepened their commitment to the Apostolic Faith.

Section V: Lasting Legacies of the Kansas Revivals

The revivals in Galena and Baxter Springs were far more than a localized spiritual awakening; they were the foundational events that transformed Pentecostalism from a failed theological experiment into a viable, expansive movement.

Their legacies are profound, encompassing the creation of an evangelistic workforce, the establishment of a direct lineage to the Azusa Street Revival, and the solidification of a doctrinal framework that would both define and divide the movement for decades to come.

The Apostolic Faith on the Move: Personnel and Momentum

Perhaps the most immediate and consequential legacy of the Galena revival was that it provided Charles Parham with the two resources he had critically lacked after the Topeka failure: dedicated personnel and financial support.1

The hundreds of conversions in Galena created a pool of zealous new believers, from which Parham “gathered a group of young coworkers” who were willing to dedicate their lives to spreading the message.7 This group, which included future leaders like Howard A. Goss, was organized into traveling “bands” that would go from town to town proclaiming the Apostolic Faith.7 This creation of a mobile evangelistic workforce was a pivotal strategic development.

The financial success of the revival, fuelled by the donations of its many enthusiastic supporters, provided the means to fund this expansion. It was this combination of human and material resources, forged in the crucible of the Galena meetings, that enabled Parham’s crucial missionary journey into Texas in the spring of 1905.6

Without the foundation laid in Kansas, this expansion, which would prove to be the most significant of his career, would have been impossible.

The Unintended Inheritance: A Direct Line to Azusa Street

The expansion into Texas, made possible by the Kansas revivals, set in motion a direct and traceable chain of events that led to the birth of the global Pentecostal movement. In Houston, Texas, in the winter of 1905, Parham opened a short-term Bible school, modelled on his earlier institutions, to indoctrinate new converts in his Apostolic Faith theology.1 One of the students who enrolled in this school was William J. Seymour, an earnest African American Holiness preacher.20

Due to the rigid segregation laws of the Jim Crow South and Parham’s own white supremacist beliefs, Seymour was not allowed to sit in the classroom with the white students. He was forced to listen to Parham’s lectures from a chair placed in the hallway, with the door left ajar.17

Despite this humiliating arrangement, Seymour fully absorbed Parham’s central and unique doctrine: that the baptism of the Holy Spirit must be accompanied by the initial physical evidence of speaking in tongues.

In early 1906, Seymour accepted an invitation to preach at a small Holiness mission in Los Angeles.

There, he preached the doctrine he had learned from Parham. This message became the theological catalyst for the Azusa Street Revival, which erupted in April 1906 and is universally recognized as the event that transformed Pentecostalism from a regional American sect into a worldwide phenomenon.1

Thus, a direct and unbroken line of doctrinal transmission can be drawn from the revival fires of Galena, which funded the mission to Texas, which enabled the teaching of William Seymour, who carried that specific teaching to Los Angeles. The Galena revival, therefore, stands as the direct theological and logistical “grandparent” of global Pentecostalism.

Doctrinal Solidification and Division

The Kansas revivals served to cement Parham’s core theological tenets as the non-negotiable foundation of his Apostolic Faith movement. The success of the meetings validated his emphasis on divine healing and, most importantly, solidified the doctrine of initial evidence as the central pillar of his theology.19

The movement gained a new sense of permanence and identity, symbolized by the construction in 1904 of the first frame church built specifically as a Pentecostal assembly in nearby Keelville, Kansas, a direct result of the revival’s growth.7

At the same time, these revivals also highlighted the deeply problematic and divisive aspects of Parham’s theology and character that would ultimately lead to his downfall. His racist ideology, manifested in his Anglo-Israelism and his segregationist practices, was an integral part of his worldview.17 His aggressive, authoritarian style and his idiosyncratic doctrines created conflict and controversy wherever he went.1

These very traits, on full display during his Kansas triumphs, prefigured the later conflicts that would marginalize him from the movement he founded. When Parham visited the Azusa Street Revival in October 1906, he was appalled by the fervent, interracial worship he witnessed, famously denouncing it as a “freak imitation of Pentecost” driven by “sensational Holy Rollers”.36 This condemnation led to a permanent schism with Seymour and the Azusa Street leadership.

This created a profound historical paradox. The Kansas revivals were absolutely essential for launching the global Pentecostal movement, providing the doctrine, the personnel, and the momentum that led directly to Azusa Street. Yet, for that movement to achieve its global potential, it had to transcend the severe limitations of its founder.

The radical egalitarianism and interracialism of the Azusa Street Revival, which were the keys to its worldwide appeal, stood in stark opposition to Parham’s segregationist vision. The Kansas revivals, therefore, were the necessary launchpad, but the rocket of global Pentecostalism could only achieve orbit by jettisoning its booster stage—namely, the leadership of Charles Parham and his attendant racial and theological baggage.

The legacy of Galena is thus both foundational and deeply fraught with the contradictions of its leader.

Conclusion: The Enduring, Complex Legacy of Galena and Baxter Springs

The revivals conducted by Charles F. Parham in Galena and Baxter Springs, Kansas, between 1903 and 1905 represent a pivotal and indispensable moment in the history of modern Christianity. They were the crucible in which the abstract theological postulates of the 1901 Topeka outpouring were forged into a viable, compelling, and expansive religious movement.

Without the events that transpired in these small Kansas towns, the Apostolic Faith movement would almost certainly have remained a curious footnote in the history of American radical religion, and the global Pentecostal movement as it is known today might never have emerged.

The Galena revival’s success was predicated on a crucial shift from the abstract promise of unverified foreign languages to the tangible, life-altering experience of divine healing. The dramatic healing of Mary Arthur provided the initial spark of credibility, and the hundreds of subsequent healings fanned it into a regional conflagration.

This emphasis on immediate, supernatural intervention, combined with Parham’s populist, anti-establishment rhetoric, resonated powerfully with the working-class population of the Tri-State Mining District. The revival provided Parham with what he had previously lacked: a large and dedicated following, a new generation of leaders such as Howard A. Goss, favorable (if fleeting) press coverage, and the financial resources to expand his mission.

The subsequent consolidation of the movement in Baxter Springs marked a strategic transition from spontaneous revivalism to organized institution-building. The establishment of a permanent headquarters and a printing press gave the Apostolic Faith a stability and a means of communication that were essential for its continued growth.

It was this organized and funded movement, born in Kansas, that carried Parham’s unique doctrine of initial evidence to Texas, where it was adopted by William J. Seymour. This direct line of doctrinal inheritance firmly establishes the Kansas revivals as the immediate precursor to the world-altering Azusa Street Revival.

Yet, the legacy of Galena and Baxter Springs is as complex and contradictory as the man at its center.

The revivals solidified a theological framework that would define Pentecostalism, but they also took place under the leadership of a deeply flawed figure whose racism and controversial secondary doctrines would ultimately lead to his repudiation by the very movement he ignited.

The revivals stand as a testament to a profound historical paradox: they were the necessary catalyst for a global spiritual phenomenon, yet the ultimate success of that phenomenon depended on its ability to move beyond the racial and theological limitations of its catalyst.

In the final analysis, the revivals in Galena and Baxter Springs were the indispensable bridge between a theological theory formulated in Topeka and a global movement launched in Los Angeles, marking the moment when a fringe idea, championed by a controversial leader, caught fire and began its improbable journey to change the face of twentieth-century Christianity.

Works cited

- a people’s religion: the populist impulse in early kansas pentecostalism, 1901 – K-REx, accessed on September 5, 2025, https://krex.k-state.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/d20cd137-51d8-4ca5-8832-d1ee3b6c6667/content

- Howard Archibald Goss – Apostolic Archives International, accessed on September 5, 2025, https://www.apostolicarchives.com/articles/article/8801925/173184.htm

- Apostolic Faith (Baxter Springs, KS) – Jay Beaman’s Christian Pacifism, accessed on September 5, 2025, http://www.pentecostalpacifism.com/home/services/pp1/apostolic-faith-baxter-springs-ks/

- Parham, Charles Fox (1873-1929) | History of Missiology – Boston University, accessed on September 5, 2025, https://www.bu.edu/missiology/missionary-biography/n-o-p-q/parham-charles-fox-1873-1929/

- PARHAM, CHARLES FOX (1873-1929) | Encyclopedia of the Great Plains, accessed on September 5, 2025, https://plainshumanities.unl.edu/encyclopedia/doc/egp.rel.038.html

- American Pentecost | Christian History Magazine, accessed on September 5, 2025, https://christianhistoryinstitute.org/magazine/article/american-pentecost

- Charles Fox Parham – Wikipedia, accessed on September 5, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Fox_Parham

- The Original Apostolic Faith Movement – 1901, accessed on September 5, 2025, https://www.apostolicarchives.com/articles/article/8801925/173157.htm

- of Charles F. Parham – Apostolic Archives International, accessed on September 5, 2025, https://www.apostolicarchives.com/articles/article/8801925/173673.htm

- Biography for Charles F. Parham – Healing and Revival, accessed on September 5, 2025, https://www.healingandrevival.com/BioCFParham.htm

- God’s General Charles Fox Parham :. Roberts Liardon, History, Video – iUseFaith, accessed on September 5, 2025, https://www.iusefaith.com/gods-general-charles-fox-parham-history-language-en-article-362

- Charles Parham 1873-1929 – Revival Library, accessed on September 5, 2025, https://revival-library.org/heroes/charles-parham/

- Pentecostalism in America | Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History, accessed on September 5, 2025, https://oxfordre.com/americanhistory/display/10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.001.0001/acrefore-9780199329175-e-878?d=%2F10.1093%2Facrefore%2F9780199329175.001.0001%2Facrefore-9780199329175-e-878&p=emailAy9wQ78Mqb1LI

- Strange History of Pentecostalism – Wayoflife.org, accessed on September 5, 2025, https://www.wayoflife.org/database/strangehistory.html

- Charles Fox Parham | Encyclopedia.com, accessed on September 5, 2025, https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/charles-fox-parham

- Giants of the Faith: Charles Parham, The Architect of Pentecostal Theology, accessed on September 5, 2025, https://revealingthechristianlife.org/2025/01/24/giants-of-the-faith-charles-parham-the-architect-of-pentecostal-theology/

- Who was Charles Parham? | GotQuestions.org, accessed on September 5, 2025, https://www.gotquestions.org/Charles-Parham.html

- Pentecostalism – Think on These Things, accessed on September 5, 2025, https://tottministries.org/pentecostalism/

- Charles F. Parham, Indefatigable Toil and Launching the World …, accessed on September 5, 2025, https://www.evangel.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/IJPM-7-1-2-Nelson-Parham.pdf

- Charles Parham – Biography – Dr Larry Martin, accessed on September 5, 2025, https://www.drlarrymartin.org/about%20charles%20parham.htm

- Galena, Kansas – America’s First Pentecostal Congregation – Apostolic Archives International, accessed on September 5, 2025, https://www.apostolicarchives.com/articles/article/8801925/174016.htm

- With Signs Following (Newsletter 4-4) – apostolic information service, accessed on September 5, 2025, https://www.apostolic.edu/with-signs-following-newsletter-4-4/

- Galena, Kansas – 1903 – Apostolic Archives International, accessed on September 5, 2025, https://www.apostolicarchives.com/articles/article/8801925/173183.htm

- Pentecostal Beginnings 1901 – Revival Library, accessed on September 5, 2025, https://revival-library.org/histories/1901-on-pentecostal-beginnings/

- “Brought into the Sphere of the Supernatural”: How Speaking in Tongues Empowered Early Pentecostals Inaugural Lecture, Wednesday, September 13, 2006 – Evangel University, accessed on September 5, 2025, http://www.evangel.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/How-Tongues-Empowered-by-Gary-McGee.pdf

- A Fire that Cannot Be Extinguished – apostolic information service, accessed on September 5, 2025, https://www.apostolic.edu/a-fire-that-cannot-be-extinguished/

- Charles Fox Parham: “Father of Modern Pentecostalism”–and Annihilationist!, accessed on September 5, 2025, https://rethinkinghell.com/2019/07/09/charles-fox-parham-father-of-modern-pentecostalism-and-annihilationist/

- Howard Archibald Goss – Image, accessed on September 5, 2025, https://www.apostolicarchives.com/albums/album_image/9099105/8364969.htm

- Howard A. Goss – Wikipedia, accessed on September 5, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Howard_A._Goss

- Baxter Springs, Kansas – Apostolic Archives International, accessed on September 5, 2025, https://www.apostolicarchives.com/articles/article/8801925/173185.htm

- The Houston Connection – 1905-1906 – Apostolic Archives International, accessed on September 5, 2025, https://www.apostolicarchives.com/articles/article/8801925/173188.htm

- Pentecostal Historical Timeline – Apostolic Archives International, accessed on September 5, 2025, https://www.apostolicarchives.com/historical-timeline.html

- The Apostolic Faith – Baxter Springs, Kansas – Charles F. Parham – Digital Showcase, accessed on September 5, 2025, https://digitalshowcase.oru.edu/apostolic_faith/

- The Holiness and Pentecostal Families in Religions of America | Roger G. Robins – Gale, accessed on September 5, 2025, https://www.gale.com/intl/essays/roger-robins-holiness-pentecostal-families-religions-of-america

- Parham’s Texas Ministry and William Seymour – Religion in Kansas Project, accessed on September 5, 2025, https://ksreligion.omeka.net/exhibits/show/the-roots-of-pentecostalism-ks/beginning-of-pentecostalism/parham-s-texas-ministry

- A Gracious, Truth-Telling Biography – U.S. Missions, accessed on September 5, 2025, https://usmissions.ag.org/sharedcontent/influence2/A-Gracious-Truth-Telling-Biography?D={4B4FD4E1-B62F-46BB-B5DF-6939D64C2F9D}

- A Gracious, Truth-Telling Biography – Influence Magazine, accessed on September 5, 2025, https://influencemagazine.com/Reviews/A-Gracious-Truth-Telling-Biography

- Charles F. Parham: Learning From Errors in Church History | A Twisted Crown of Thorns ®, accessed on September 5, 2025, https://atwistedcrownofthorns.com/2011/04/20/charles-f-parham-learning-from-errors-in-church-history/