1903 Revival in Dongjia’an

Mary Culler White in later life

I. Introduction: The Crucible of the Early 20th Century

Mary Culler White in later life

1.1 Defining the 1903 Dongjia’an Revival: A Distinct Event within a Broader Movement

The 1903 Dongjia’an Revival stands as a pivotal, yet often understated, event in the history of Protestant missions in China. Occurring in the village of Dongjia’an, near Mount Lao, this movement is recognized not as an isolated phenomenon but as a specific, powerful manifestation of the complex spiritual, social, and political dynamics of its era.1

The revival’s narrative, centered on a small class of women and the missionary who taught them, offers a micro-paradigm for understanding the broader “golden age” of Christianity that swept through China in the early 20th century.2

The following report provides a detailed examination of the Dongjia’an Revival, exploring its historical antecedents, its catalytic figures, its immediate and far-reaching impact, and its enduring legacy within Chinese religious history.

1.2 Historiography of Protestant Missions and Revivals in China

The historical experience of Protestantism in modern China is often described as a tumultuous journey of highs and lows.4 To properly analyze the Dongjia’an Revival, it is essential to establish a scholarly framework that recognizes the interplay of three core forces identified by historians: foreign missionaries, Chinese Christians, and the Chinese state.4

For much of the 19th century, the Qing state and traditional elites actively rejected Protestantism, creating a climate of tension and violence.4 However, the period after 1900 saw a fundamental shift in these dynamics, which is crucial for understanding the context of the Dongjia’an Revival.

The primary account of the revival comes from the missionary at its center, Louisa Vaughan, in her book Answered or Unanswered? Miracles of Faith in China.1 Her narrative, a powerful testimony of faith, provides a vivid, firsthand perspective but must be interpreted alongside other historical data to construct a nuanced and comprehensive historical record.

II. Antecedents: The Post-Boxer Rebellion “Golden Age”

2.1 From Catastrophe to Unprecedented Growth: The Paradox of 1900-1920

The Boxer Rebellion of 1900 marked a catastrophic low point for Christianity in China. Originally a regional anti-Christian and anti-foreign movement, it escalated into an international crisis that resulted in the slaughter of thousands of Chinese believers and the destruction of mission facilities.3

The period immediately following this upheaval, however, saw a remarkable and paradoxical turnaround. Christianity entered what many scholars consider a “golden age,” with the number of Chinese converts skyrocketing and the religion enjoying unprecedented growth.2

This dramatic revival was not a random occurrence but a direct consequence of the political and social milieu.

After the defeat of the Boxers, xenophobic forces were neutralized, leading to a significant decrease in anti-Christian violence.3 The Qing government, now operating under a new, more liberal political environment, adopted a series of measures favorable to foreign missionaries and their religious work.3

This included governmental compensation for losses, which facilitated the rapid rebuilding of churches and the reestablishment of congregations.3 The Dongjia’an Revival, therefore, did not emerge in a vacuum. It was a specific, powerful manifestation of a broader, favorable trend in which a new political and social openness created a fertile ground for evangelism.

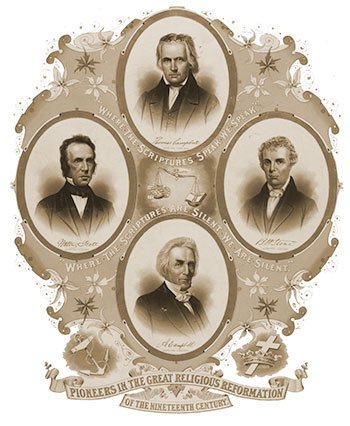

2.2 The Precedent of Wonsan: The Korean Revival of 1903

The spiritual climate in East Asia at the turn of the century was also a significant antecedent to the events in Dongjia’an. The 1903 Wonsan, Korea Revival, occurring in the same year, is a notable parallel and precedent.6

This movement was initiated by a prayer meeting started by Methodist missionary Mary Culler White and Presbyterian missionary Louise Hoard McCully, which soon expanded to include other missionaries.7

The pivotal moment came when Dr. Robert A. Hardie, a medical missionary, publicly confessed his personal failures, including his racial prejudice against the Korean people and his professional frustration at not seeing any “fruits” from his years of work.7

This sincere and public outpouring of brokenness and repentance from a missionary leader became a catalyst for a corporate revival.8

The Wonsan congregation reciprocated, and deep confession and reconciliation ensued.7 This move of God spread, leading to Dr. Hardie holding revival meetings for three years, and in 1904 alone, 10,000 Koreans were converted.8

The Wonsan Revival thus established a pattern where a leader’s recognition of their human limitations and a turn to perceived divine intervention were seen as a prerequisite for a powerful spiritual movement.

This thematic link of brokenness and revival provides a crucial comparative context for understanding the events that unfolded in Dongjia’an, where a similar paradigm of personal humility and earnest prayer would unlock the spiritual breakthrough.

Table 1: Key Figures in Early 20th Century East Asian Revivals

| Name | Revival Location | Mission Affiliation | Key Role | Thematic Contribution |

| Louisa Vaughan | Dongjia’an, China | Presbyterian | Central missionary leader | Private brokenness and prayer; teaching women. |

| Dr. Robert A. Hardie | Wonsan, Korea | Methodist/Medical | Keynote speaker/revivalist | Public confession of personal and professional failure. |

| Jonathan Goforth | Manchuria, China | Presbyterian | Missionary revivalist | Traveling speaker; confession and repentance as revival triggers. |

III. The Catalytic Figure: The Ministry of Louisa Vaughan

3.1 From Linguistic Mastery to Pastoral Despair: Vaughan’s Preparation and Initial Challenges

Louisa Vaughan, a Presbyterian missionary, was the central human figure in the Dongjia’an Revival. Her ministry was built on a foundation of rigorous preparation; she had dedicated five years to language study to effectively communicate the Christian message.1

Her first class was in the village of Dongjia’an, a group of 25 “pre-Christian ladies” who were assembled by a Chinese pastor.1 Vaughan’s goal was to teach them the basics of Christianity over a ten-day period, hoping to lead them to a point of faith.1

However, Vaughan was immediately confronted with a deeply discouraging situation. The women were uneducated and illiterate, and they themselves expressed profound self-doubt.1 Statements such as “My mind and heart are as hard and dark as mahogany wood” and “I have no brains” were common, leading Vaughan to feel that her task was “humanly impossible”.1

This despair set the stage for the catalytic event that followed.

3.2 The Power of Prayer: Vaughan’s Theological Foundation and Breakthrough

In response to her discouragement, Vaughan turned to prayer, believing that her situation required a miracle.1 Her ministry was underpinned by a theology of faith and prayer, rooted in the belief that genuine revival is a “visitation of the Holy Spirit” and a direct response to a believer’s fervent request.5

Vaughan’s approach was practical; she taught the women a simple prayer: “Heavenly Father, forgive me my sins, cleanse me from them in the precious blood of Christ, and fill me with the Holy Spirit; I ask in Jesus’ name”.1

On the second day of teaching this prayer, one of the women began to weep, confessing her sins. This initial spiritual breakthrough led to a cascade of conversions over the next few days, until the entire class of 25 women had embraced Christianity.1

The transformation was profound; the women, who had initially been resistant to learning, became “extremely eager students,” consuming all of Vaughan’s time with their quest for knowledge.1

3.3 The Indigenous Dimension: The Role of the Chinese Pastor and Believers

While Louisa Vaughan is the central figure in the recorded narrative, a crucial detail reveals the indigenous leadership that provided the foundation for her work. The initial group of 25 women was “assembled by a Chinese pastor”.1

This single, seemingly minor detail is significant. It demonstrates that the Dongjia’an Revival was not solely a foreign-led initiative but a collaborative effort rooted in existing indigenous Christian work.

The pastor’s role was not merely administrative; he was the key indigenous leader who identified and gathered the receptive audience, demonstrating that the revival’s success was fundamentally tied to the groundwork laid by Chinese believers.

This highlights the vital contributions of the Chinese church in preparing the ground for missionary efforts to be effective.

IV. The Spark and the Spread: Converts and Reach

4.1 The Initial Outpouring: The Conversion of the 25 Women

The conversion of the initial class of 25 women was the foundational event of the revival. This group, composed of pre-Christian inquirers, represented a full-scale spiritual transformation of a single, targeted community.1

The event demonstrated the power of the methodology employed—simple, persistent prayer and teaching—to produce a complete conversion among a group that was initially resistant and culturally predisposed to a belief in their own intellectual inadequacy.1

4.2 A Paradigm of Replication: The Testimony of Mrs. Wang

The true paradigm of the revival’s expansion is exemplified by the testimony of Mrs. Wang. She was not part of the initial class but was drawn to Vaughan’s teaching out of curiosity.1 Upon hearing the simple prayer, she was converted, a process she described as a direct, spiritual breakthrough.1 Her story then became a model for how the revival spread relationally.

After her conversion, she faced persecution from her alcoholic husband, who beat her so severely that she was bedridden for a month.1 Despite this, she continued to pray for him for six months.1

4.3 The Ripple Effect: The Conversion of Mr. Wang and the Multiplication of Discipleship

The climax of Mrs. Wang’s story is the miraculous conversion of her husband, Mr. Wang, who had been a drunkard for 31 years.1 While on his way to a wine shop, he heard a voice telling him, “Don’t go in there, go home!” a command so startling that he dropped his purse.1 After this occurred a second time, he went home, confused and frightened, and asked his wife if he was losing his mind.1

Mrs. Wang explained that it was Jesus speaking to him and shared the Gospel.1 He was converted that day, gave up drinking, and his entire family became members of the church, sending their children to a Christian school.1 This chain of events—from one woman’s personal conversion to her family’s transformation—demonstrates a decentralized model of discipleship multiplying disciples.1

4.4 Quantifying the Impact: An Analysis of the 1,500 Reported Conversions

Louisa Vaughan’s ministry in China over the next decade replicated the initial success in Dongjia’an. She reportedly held five to six similar classes per year, with a claimed 100 percent success rate, leading to approximately 1,500 conversions from these classes alone.1

The revival’s spread, as evidenced by the Wang family testimony, was not driven by a formalized, large-scale campaign but by personal witness and social networks, which have historically been a primary driver of religious growth in rural areas.10

This model of a deeply rooted, relational spread contrasts with the more organized, public approach of other contemporary revivals, such as the Manchurian Revival, where “bands of revived Christians went here and there preaching the Gospel”.11

The influence of the Dongjia’an Revival on the “surrounding rural and urban areas” 12 likely followed this relational pattern, with new believers becoming the primary agents of evangelism within their own communities.

Table 2: The Transformative Reach of the Dongjia’an Revival

| Aspect of Reach | Initial Impact | Case Study Example | Broader Scope |

| Recruitment | A Chinese pastor assembled 25 women. | Mrs. Wang joined out of curiosity. | Over 1,500 converts over 10 years. |

| Conversion Catalyst | A simple prayer taught by Vaughan. | A supernatural voice heard by Mr. Wang. | A reliance on the Holy Spirit’s intervention.5 |

| Propagation Model | Missionary-led class. | Mrs. Wang’s personal witness to her family. | Disciples multiplying disciples.1 |

| Primary Arena | Vaughan’s classes in Dongjia’an. | Family and community social networks. | Surrounding rural and urban areas.12 |

| Lasting Outcome | The entire class of 25 women converted. | The Wang family joined the church and their children attended a Christian school. | Revived churches and lay-led services.13 |

V. Legacy and Scholarly Reflections

5.1 From Revival to Established Church: The Institutional Impact of the Dongjia’an Movement

The long-term institutional legacy of the Dongjia’an Revival, while not fully detailed in the provided materials, can be inferred from its characteristics and the general patterns of the era.

The revival’s emphasis on indigenous leadership, as demonstrated by the Chinese pastor who assembled the initial class, and its success through personal witness, created a precedent for a more self-sustaining model of Christianity.

Later reports of the broader Shandong Revival note that a significant result of these movements was the revival of “spiritually-dead churches” and the emergence of lay-led services when no missionary was present.13

This suggests that the Dongjia’an movement’s decentralized, relational spread contributed to the establishment of more resilient, indigenous church structures.

5.2 Echoes in a Generation: The Dongjia’an Revival’s Contribution to the Later Shandong and Manchurian Revivals

The Dongjia’an Revival serves as a foundational event for later, more well-documented movements, such as the Manchurian Revival and the broader Shandong Revival of 1927-1935.13 These later movements shared key characteristics with the Dongjia’an event, including a focus on repentance, confession, and the crucial involvement of Chinese Christians.8

However, the later revivals, particularly the Shandong Revival, were also noted for “Pentecostal excess” and charismatic practices such as divine healings and speaking in tongues, which led to concern among Southern Baptists in the USA.13

This contrasts with the Dongjia’an narrative, which focuses on the more personal, emotional, and relational dimensions of conversion, such as weeping and confession. This contrast highlights a potential evolution in the nature of Chinese revivals during the period.

5.3 The Primary Record: Louisa Vaughan’s Writings as a Historical and Theological Artifact

The primary source for the Dongjia’an account is Louisa Vaughan’s book, Answered or Unanswered? Miracles of Faith in China.5 The book is a collection of stories intended to be a “witness-bearing” of faith, focused on the power of prayer and the “reality of God”.5

It is important to acknowledge that this primary historical record is an anecdotal, faith-based account from an invested missionary. While the user query asks for “lasting benefits,” and external information on the long-term institutional legacy is not available 1, the very nature of the recorded legacy provides a significant understanding.

The lasting benefit is not an institutional one but a paradigmatic one, found in the multiplication of disciples, the personal transformation stories, and the published testimony that became a resource for later generations of believers.6

This suggests that the true legacy of this revival is found in its demonstration of the power of personal witness and testimony are often a means of propagation.

5.4 Beyond the Anecdotal: Critical Analysis and Academic Interpretations of the Revival

The Dongjia’an Revival can be analyzed through broader academic lenses. The story of Mr. Wang’s deliverance from alcoholism and his family’s subsequent betterment 1 aligns with Marcel Mauss’s paradigm of “The Gift,” where conversions are motivated by a complex mix of spiritual and material benefits.

The revival’s success with women who were illiterate and considered “ignorant” 9 also demonstrates the suitability of its methodology. The reliance on simple, non-literary prayer and oral testimony was uniquely effective for an audience that had previously been told they “had no brains” and could not learn.1

This approach circumvented the barriers of traditional education and literacy, making the Christian message accessible to all. The focus on personal and familial transformation, rather than complex theological instruction, allowed the movement to take deep root in a rural, non-literate community.

VI. Conclusion: A Nuanced Understanding of a Pivotal Event

6.1 Synthesizing the Findings: Key Drivers of the Revival

The 1903 Dongjia’an Revival was a product of a complex confluence of forces.

Its success was driven by a unique set of circumstances: the favourable political and social conditions that followed the Boxer Rebellion, a spiritual catalyst rooted in a missionary’s personal brokenness and persistent prayer, and a methodology of personal evangelism and teaching that was uniquely tailored to its initial, non-literate audience.

The crucial, though understated, role of indigenous Chinese leadership, exemplified by the pastor who assembled the initial class, provided the vital bridge between the foreign missionary effort and the local community.

6.2 The Dongjia’an Revival’s Enduring Place in Chinese Religious History

While the Dongjia’an Revival may have been small in scale compared to later movements, it was a paradigmatic event in the history of the Chinese church. Its true legacy is not found in institutional records but in its demonstration of “disciples multiplying disciples”.1

This pattern of indigenous, relational growth became a hallmark of the extraordinary expansion of the Chinese church throughout the 20th century.

6.3 Broader Implications for the Study of Missions and Indigenous Faith Movements

The Dongjia’an Revival offers a compelling case study for understanding the complex interplay between foreign missionary efforts and indigenous agency. It underscores that while foreign missionaries often provided the initial impetus and theological framework, the long-term propagation and resilience of the faith rested on the shoulders of the Chinese believers themselves.

The story of Mrs. Wang’s perseverance and her husband’s conversion, a narrative that spread through personal testimony rather than public proclamation, serves as a powerful reminder of how grassroots, bottom-up movements can achieve profound and lasting transformation within a culture.

Works cited

- 1903 Dongjia’an, China Revival – BEAUTIFUL FEET, accessed on September 2, 2025, https://romans1015.com/dongjiaan/

- Triumph after Catastrophe: Church, State and Society in Post-Boxer China, 1900-1937, accessed on September 2, 2025, https://nsuworks.nova.edu/pcs/vol16/iss2/3/

- Triumph after Catastrophe: Church, State and Society … – NSUWorks, accessed on September 2, 2025, https://nsuworks.nova.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1106&context=pcs

- Protestantism and Modern China: Rejection, Success, Disaster … – Brill, accessed on September 2, 2025, https://brill.com/display/book/9789004304642/B9789004304642_022.pdf

- Answered or Unanswered: Miracles of Faith in China by Louisa Vaughan, Paperback | Barnes & Noble®, accessed on September 2, 2025, https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/answered-or-unanswered-louisa-vaughan/1114969879

- 2514 Accounts of Revival – BEAUTIFUL FEET, accessed on September 2, 2025, https://romans1015.com/accounts-of-revival/

- 1903 Wonsan, Korea Revival – BEAUTIFUL FEET, accessed on September 2, 2025, https://romans1015.com/1903-wonsan-korea/

- Korean Revivals Wonsan 1903 and Pyongyang 1907 – Korea, accessed on September 2, 2025, https://www.byfaith.co.uk/paul20102.htm

- Louisa Vaughan (1900s) – Asia Harvest, accessed on September 2, 2025, https://www.asiaharvest.org/china-resources/shandong/louisa-vaughan

- The Missionary Movement in China – Squarespace, accessed on September 2, 2025, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/533197c8e4b02aa0f34bb043/t/6106dad81a24ff47a8e1e764/1627839194301/Missionary+Movement+Introduction+to+the+Literature+-+Houseworth+edit+10.pdf

- Manchurian revival – Wikipedia, accessed on September 2, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Manchurian_revival

- Shades of Gray in the Changing Religious Markets of China – Brill, accessed on September 2, 2025, https://brill.com/display/book/9789004456747/BP000010.pdf

- Shandong Revival – Asia Harvest, accessed on September 2, 2025, https://www.asiaharvest.org/china-resources/shandong/1930s

- The Secret Shantung Revival Of 1927 – YouTube, accessed on September 2, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_DfKucrF4Yc

- barnesandnoble.com, accessed on September 2, 2025, https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/answered-or-unanswered-louisa-vaughan/1114969879#:~:text=Overview,stories%20testifying%20to%20that%20reality.

- A brief history of the Baptists of Louisa County, Virginia to 1865 – UR Scholarship Repository, accessed on September 2, 2025, https://scholarship.richmond.edu/context/masters-theses/article/1966/viewcontent/Musselwhite_Roscoe_1958.pdf