1900-1902 The Australasian Revival

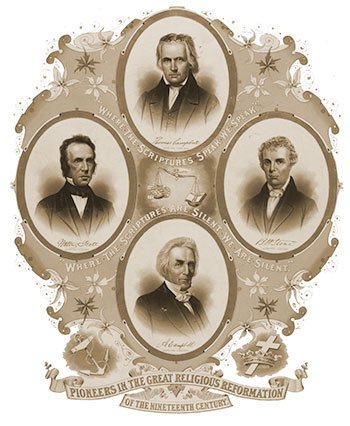

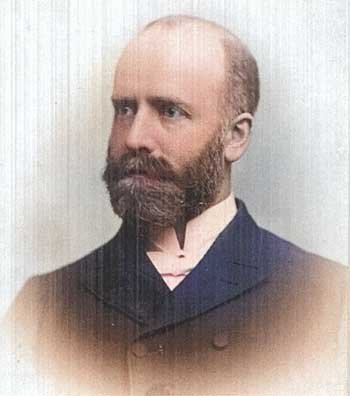

Reuben Archer Torrey

Introduction to the Australasian Revival

Many contemporary students of revival correctly distinguish between the highly effective campaigns of D.L. Moody and Reuben A. Torrey and what might be considered ‘authentic’ revivals.

However, when viewed within the broader history of global revivalism, the prayer, expectation, and missionary zeal these campaigns inspired were instrumental in creating the necessary preconditions for the worldwide revival of 1904.

At the dawn of the 20th century, the fledgling nations of Australia and New Zealand stood at a spiritual crossroads. The Christian revivals that swept through their cities, culminating in the monumental evangelistic campaigns of 1902, were far more than a spontaneous eruption of religious fervour.

These events were the meticulously planned climax of decades of theological anxiety, highly organized interdenominational prayer, and the strategic mobilization of a trans-national evangelical network.

The period between 1900 and 1901 represents the final, intensive phase of preparation for the pivotal events that followed, a period in which a deep sense of spiritual anticipation was cultivated across Australasia.

The “Australasian Awakening” was a defining moment for the two young nations, consolidating a dominant Christian social and moral identity during the very years of Federation in Australia and nascent nationhood in New Zealand.

Critically, this regional phenomenon did not remain contained. It acted as a powerful and demonstrable catalyst for the major global revivals that subsequently erupted in Wales and the United States, positioning Australasia, for a time, as an unlikely epicenter of global spiritual influence.

This report will examine the complex antecedents that prepared the ground for revival, profile its key architects, narrate the events, and assess their profound and multifaceted legacy.

Section 1: The Prepared Ground: Antecedents to the Australasian Revival

1a. Faith, Doubt, and the Colonial Christian Consensus

The socio-intellectual climate of late 19th-century Australia and New Zealand was characterized by a profound tension between entrenched religious belief and the unsettling currents of modernity. The colonies were experiencing a significant “crisis of faith” among their educated classes, a direct consequence of scientific discoveries.¹

Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (1859), arriving in Australia only months after its London release, precipitated widespread public debate. Darwin’s theories presented a direct challenge to long-standing Christian doctrines of Creation, shaking the foundations of faith.¹ These debates permeated Australian cultural life through public lectures and vigorous discussion, paralleling the intellectual turmoil in Britain.¹

Yet, this intellectual ferment existed alongside a society where Christianity was deeply woven into the institutional and social fabric. Both Australia and New Zealand were fundamentally shaped by their British colonial heritage, which included not only language and government but also the pervasive influence of Judeo-Christian ethics.²

The churches were far more than places of worship; they were central hubs of community life, providing the bulk of social welfare, charity, and education.³ In South Australia, which prided itself on having no established state church, about 40% of the population still regularly attended church or Sunday school at the turn of the century.³

Churches were ubiquitous, serving as vital social centers and assuming a de facto role as guardians of public morality, with their members actively engaged in politics to ensure legislation reflected Christian principles.³

This contradiction—a crisis of faith among the elite coexisting with the pervasive social power of the churches—created a unique dynamic. For the robust evangelical communities within the Nonconformist denominations and evangelical wings of the Anglican and Presbyterian churches, this crisis acted as a powerful motivating force.

The perceived threat engendered a profound sense of urgency. What was required was a dramatic, public, and undeniable demonstration of God’s power. In this context, the theology of revivalism offered the perfect spiritual and strategic tool.

A massive, city-shaking revival would serve not only to save individual souls but also to function as a divine rebuttal to the claims of a secularizing world, rendering the abstract arguments of Darwinists moot. The “crisis of faith,” therefore, directly fueled the intensity of the prayer movements that would lay the revival’s foundation.

1b. The Denominational Tapestry and the Evangelical Ascendancy

The religious landscapes of Australia and New Zealand were diverse and competitive, mirroring their British and Irish origins. With no single established church, a vibrant religious marketplace was fostered.³ The major denominations were the Anglicans, Scottish Presbyterians, Roman Catholics, and the various branches of Methodism.³

A distinctive feature of Australian religious life was the strength of the “Dissenting” or Nonconformist churches—primarily the Methodists, Baptists, and Congregationalists. In colonies like South Australia, these groups were so prominent it was described as a “Paradise of Dissent”.³

These denominations, along with fervent evangelical wings within the larger churches, were the primary carriers of revivalist theology.⁷ Their emphasis on personal conversion and spiritual zeal created a culture predisposed to mass evangelism.⁹

By the late 19th century, a strongly evangelical ethos pervaded most Protestant denominations in Australia, many of whom employed their own evangelists and maintained a persistent prayer focus on the need for a national spiritual awakening.⁷

New Zealand’s religious composition was broadly similar. Anglicans were the largest group (around 40%), followed by Presbyterians, who were concentrated in the Scottish settlements of Otago and Southland.⁶ Methodists, though smaller, were noted for being the most diligent churchgoers.¹⁰

A key characteristic of New Zealand’s Protestant dissenters was their high level of cooperation in social reform. Groups like the Methodists, Presbyterians, and Baptists worked together to campaign against gambling and alcohol and were instrumental in the successful push for women’s suffrage in 1893.⁶

This pre-existing network of interdenominational cooperation provided a crucial framework for the unified evangelistic efforts that would follow.

1c. Indigenous Spiritualities in Transition: A Parallel Narrative

To fully comprehend the context of the Australasian revivals, it is essential to acknowledge the parallel spiritual narrative of the Indigenous peoples. In New Zealand, the 19th century had witnessed a widespread conversion of Māori to Christianity. By the mid-1840s, a larger proportion of Māori than Britons regularly attended Christian services.⁶

This was not passive acceptance; Māori made Christianity their own. However, colonization, the New Zealand Wars of the 1860s, and systemic land alienation led to disillusionment with missionary churches, often seen as complicit with the settler government.

This gave rise to powerful, independent Māori Christian movements like Pai Mārire and Ringatū, which blended Christian and Māori beliefs and served as vehicles for political resistance and cultural self-determination.⁶

In Australia, the relationship between Christianity and Aboriginal peoples was more starkly defined by the colonial frontier. The primary point of contact was the mission system.¹³ These missions occupied an ambiguous space, sometimes providing a physical “haven from the hell of life on the Australian frontier” from violence and starvation.¹³

However, they were also key instruments of state “protection” and assimilation policies, facilitating colonization by forcibly removing people from their lands and systematically suppressing Indigenous languages and cultures.¹³ Engagement with Christianity for Aboriginal peoples was thus inextricably linked to the trauma of dispossession.

This context is critical. While framed in universal terms, the 1900-1902 revivals functioned as a powerful affirmation of the dominant settler culture’s religious and moral worldview. A mass movement that revitalizes and unifies the dominant culture’s religious framework inherently strengthens its hegemonic position.

For Indigenous peoples, this was not a neutral spiritual event. For Māori, forging their own forms of Christianity as resistance, this wave of Pākehā-centric revivalism was another assertion of settler power. For Aboriginal peoples on missions, a revival among the white population would likely translate into more zealous assimilationist policies.

Therefore, the revival’s “lasting benefits” must be viewed as unfolding within a context of ongoing colonization.

Section 2: The Architects of Revival: Personalities and Prayer Movements

2a. A Concert of Prayer: The Rise of Interdenominational Prayer Unions

The revivals of 1901-1902 were the direct result of a highly organized prayer movement that had been building for over two decades. This was a deliberate campaign rooted in the “new measures” revivalism of Charles G. Finney, who taught that revival could be promoted by human means.⁷ This conviction—that prayer and holiness were necessary preparations for an outpouring of the Holy Spirit—was foundational.⁷

Beginning in the 1880s, “Prayer Unions,” often fostered by female evangelists like Mrs. Margaret Hampson, grew rapidly across the colonies.⁸ Promoted by clergymen like Anglican Dean H. B. Macartney, these unions mobilized thousands of laypeople into a coordinated effort, meeting weekly with the specific goal of praying for a widespread spiritual revival.⁸

In Melbourne, a particularly influential group was formed in the 1890s by Presbyterian minister Rev. John MacNeil.¹⁷ Known as “The Band,” this group of ministers from various denominations met every Saturday, convinced they were “living on the wrong side of Pentecost” and praying with fervent intensity for “the big revival”.¹⁸

MacNeil’s book, The Spirit Filled Life, became an international success, further fuelling the spiritual hunger for revival.¹⁸

Following MacNeil’s death, the movement he helped ignite intensified. “The Band” continued, and a network of home prayer meetings grew exponentially.¹⁸ By the time the evangelistic campaign began in Melbourne, this grassroots movement had reached a staggering scale: 1,700 distinct home prayer groups, attended by an estimated 15,000 people, were meeting weekly across the city to pray for the mission’s success.¹⁸

This vast network created a powerful sense of unity and spiritual anticipation that saturated the city’s evangelical community.

2b. The Trans-Pacific Connection: Moody, Torrey, and Alexander

The ambitions of the Australian prayer movement were global. Leaders of Melbourne’s Evangelization Society of Australasia (ESA) set their sights on securing the world’s most renowned evangelist: Dwight L. Moody.¹⁷ In 1898, a petition with 15,300 signatures was sent to the Moody Bible Institute, inviting him to Australia.¹⁸

Moody’s death in 1899 prevented his coming, but the connection was forged. The mantle was taken up by his designated successor, Reuben Archer Torrey (R.A. Torrey), Superintendent of the Moody Bible Institute.¹⁸ Torrey was a towering figure in the emerging Fundamentalist movement, a powerful preacher representing core commitments of interdenominational evangelicalism: biblical authority, world missions, holiness piety, and faith in the power of revival.²¹

Torrey was accompanied by Charles M. Alexander, a gifted and charismatic song leader whose innovative methods would prove just as crucial to the campaign’s success.²¹ Their arrival in 1902 connected the local prayer movements of Australasia directly to the sophisticated international revivalist network, bringing world-class leadership to a field that had been diligently prepared.²³

2c. Local Harvesters: The Ministry of Itinerant and Resident Evangelists

The success of Torrey and Alexander was built upon a foundation laid by countless local evangelists. The religious culture was already saturated with evangelistic activity. Denominations like the Methodists had a long tradition of employing itinerant evangelists and holding revival services.⁸

Figures like David O’Donnell conducted successful missions throughout the 1880s and 1890s.⁸ Parachurch organizations also created a culture of zealous evangelism. The early Salvation Army combined social work with aggressive open-air preaching, while the Y.M.C.A. held large-scale meetings in public venues.⁸

The Christian Endeavour Movement mobilized tens of thousands of young people into societies dedicated to prayer and evangelism, functioning as a massive branch of the Prayer Union Movement.⁸

Organizers of the 1902 campaign masterfully integrated this existing infrastructure. The Melbourne mission was a city-wide blitz. In conjunction with Torrey’s headline meetings, the ESA appointed 50 local evangelists to preach simultaneously in 42 halls and 30 large tents across the suburbs.¹⁸

This multi-layered approach ensured the revival’s message reached every corner of the metropolis, leveraging both international star power and deep local resources.

Section 3: The Fire Descends: A Narrative of the Great Revivals (1901-1902)

3a. The Melbourne Mission: Epicenter of the Awakening

The Torrey-Alexander campaign, beginning in Melbourne in April 1902, is considered the epicenter of the Australasian Awakening and a turning point in Torrey’s career, making him a global revivalist.²¹ The scale of the meetings was unprecedented.

The central venue was the cavernous Royal Exhibition Building, which regularly hosted crowds of 10,000 people per night.²⁰ Total weekly attendance across all venues was estimated at a quarter of a million people, equivalent to half the population of Melbourne.²⁰

A key methodological element was the systematic use of “after meetings”.²² Those who came forward as “enquirers” were immediately taken to separate rooms for personal counseling with trained workers.

This process was designed to consolidate their decision, ensure they understood the gospel, and connect them with a local church. It was a highly organized approach to securing and recording conversions.²²

The results were dramatic. In four weeks, the Melbourne mission recorded 8,642 professions of faith.¹⁹ The phrase “The Big Revival has begun, glory be to God,” became a common greeting.¹⁸

Reports were filled with accounts of transformed lives, including “infidels, publicans, and actresses”.¹⁸ In some districts, the effect on public morality was so pronounced that police reportedly had very little work to do.¹⁸

3b. The Revival on the Move: Sydney, the Regions, and New Zealand

Following its success in Melbourne, the campaign toured Australia and New Zealand.²¹ In Sydney, meetings overflowed the Town Hall, with multiple simultaneous meetings held in side rooms and outside on the steps. An estimated ten thousand people heard the gospel in a single evening at that one location.²¹

The revival’s impact was also strong in regional Australia. In Geelong (pop. 28,000), total attendance exceeded one hundred thousand.²¹ Even in the tiny township of Terang, between one and two thousand people attended tent meetings.²¹ The campaign in New Zealand continued this pattern, galvanizing existing streams of evangelical piety and drawing large crowds across the dominion.²³

3c. The Sound of a New Song: The Revolutionary Role of Music

An equally crucial element to the revival’s success was the ministry of song leader Charles M. Alexander. He was not merely an accompanist but a co-architect of the revival’s atmosphere, pioneering techniques of mass musical participation.²¹ Alexander’s primary method was organizing and leading massive choirs.

In Melbourne, he assembled a choir of over 1,200 voices, which was more than a performance; it was mass audience participation that transformed the event’s emotional dynamic.²² The sound created an immersive, emotionally charged environment that fostered a powerful sense of collective spiritual experience.

Alexander also introduced a new canon of music, moving from traditional, complex hymns to newer, simpler gospel songs with direct emotional appeal. These songs became a key vehicle for the revival’s message. His influence was so profound that his famous hymn books, used worldwide for decades, originated in Melbourne during the 1902 mission.²²

This approach transformed the revival meeting from a passive lecture into an interactive, participatory experience. This methodological innovation represents a significant step in the evolution of religious mass communication and was a critical factor in the revival’s extraordinary success.

Section 4: The Enduring Legacy: Assessing the “Lasting Benefits”

4a. Institutional and Ecclesial Reformation

The revival acted as a catalyst for institutional change within Australasian Protestantism. The intense spirit of interdenominational cooperation, climaxing in the unified missions of 1902, created momentum toward formal church unity.²⁰ This bore significant fruit. In New Zealand, after years of negotiations, the Presbyterian Church of New Zealand was officially formed on October 31, 1901, a process energized by the revivalist climate.³⁰, ³¹

Similarly, in Australia, the various branches of Methodism united nationally in 1902, hastened by the shared experience of the campaigns.³³ The revivals also led to a tangible reinvigoration of church life.

Many churches were filled for years afterward, their memberships swelled by new converts.¹⁹ Influential parachurch organizations like the Australian Student Christian Movement (ASCM), founded in 1896, also drew support and energy from the spiritual awakening.³⁶

4b. From Personal Holiness to Public Morality: The Revival and Social Reform

The revival’s focus on individual holiness was directly channeled into vigorous campaigns for social reform. Protestant churches were already engaged in campaigns against gambling, alcohol, and for Sabbath observance.³ The revival provided these movements with a massive, newly energized constituency.

This was particularly evident in the movements for temperance and women’s suffrage. In New Zealand, the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) had been a primary engine of the successful 1893 suffrage campaign.⁶ In Australia, suffrage societies drew heavily on the same evangelical base galvanized by the revival.⁴³

It is no coincidence that the Commonwealth Franchise Act of 1902, granting Australian women the vote, was passed in the immediate context of the great revival.⁴⁴ The revival undeniably provided the moral passion and popular support that fuelled these progressive social reforms, contributing to an era where Australia and New Zealand were seen as “social laboratories of the world”.⁴⁵

4c. A Southern Spark for a Global Flame

Perhaps the most significant legacy of the Australasian Awakening was its role as a catalyst for major global revivals.¹⁹ The chain of influence is well-documented. Fresh from Melbourne, R.A. Torrey traveled to the Keswick Convention in England in July 1902. He testified not just of the conversions, but of the methodological key to success: the network of 1,700 “prayer circles” that had prepared the city.¹⁹

Torrey’s report electrified the convention. Attendees committed to establishing similar prayer circles across Britain to pray for a worldwide revival.¹⁹ This explosion of coordinated prayer is widely credited with preparing the ground for the famous Welsh Revival of 1904-1905.¹⁹

The Welsh Revival, in turn, was a primary influence on the Azusa Street Revival in Los Angeles in 1906, the birthplace of the global Pentecostal movement.²² This sequence marks a pivotal reversal in the flow of spiritual influence.

For a century, Australasia had been a mission field.³ In 1902, the dynamic shifted. The colonies became a source of spiritual inspiration and methodological innovation that flowed back to the imperial center and the wider world.

4d. A Contested Inheritance: The Revival and Indigenous Peoples

A complete assessment requires a critical evaluation of the revival’s legacy for Indigenous communities. For Aboriginal Australians, the revival’s energy likely translated into more vigorous assimilationist efforts on the Christian missions where many were confined.¹⁴

The revival’s success would have been seen as a divine endorsement of the “civilizing” project, intensifying pressure to abandon traditional culture. While later revivals saw the emergence of Aboriginal Christian leaders, the 1902 event was primarily a consolidation of the colonial religious establishment.¹⁹

For Māori, who had their own independent Christian traditions, the revival represented a resurgence of Pākehā religious culture at a time when they were developing prophetic movements in response to land loss.⁶ The rise of leaders like Rua Kēnana highlights a trajectory of Māori spirituality running parallel to, and often in opposition to, the mainstream settler churches.¹⁰

The revival’s focus on individual salvation did little to address the core issues of collective injustice and land rights animating these Māori Christian movements. The inheritance of the revival is thus a contested one, existing within a colonial framework that continued to marginalize Indigenous peoples.

Conclusion

The Christian revivals that culminated in Australia and New Zealand in 1902 were a complex and historically significant phenomenon. They were the orchestrated outcome of a prolonged campaign of prayer and preparation, a fervent response to the anxieties of the age, and a demonstration of a trans-national evangelical network.

The revivals profoundly reshaped the religious and social landscape of the two nations, providing impetus for church unions, energizing social reforms, and consolidating a Protestant cultural identity at a formative moment. Beyond their regional impact, they served as the southern spark that helped ignite the Welsh and Azusa Street revivals.

This legacy, however, remains deeply contested when viewed through the lens of Indigenous peoples, for whom this consolidation of settler religious culture was inextricably bound with the colonial project of assimilation.

The Australasian Awakening thus stands as a testament to the power of religious movements to shape society, while also serving as a sobering reminder that the “lasting benefits” of such events are rarely distributed equally.

Works Cited

- The Victorian Crisis of Faith in Australian Utopian Literature, 1870 …, accessed on August 27, 2025, https://www.monash.edu/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/1764212/kendal.pdf

- Culture of Australia – Wikipedia, accessed on August 27, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Culture_of_Australia

- Religion – History Hub, accessed on August 27, 2025, https://sahistoryhub.history.sa.gov.au/subjects/religion/

- A Long History of Faith-Based Welfare in Australia: Origins and Impact [accepted manuscript] – Research Bank, accessed on August 27, 2025, https://acuresearchbank.acu.edu.au/download/b49953593444c657ae0804233b2ab2cf038b186b08aa3db5a2e2ef0e853cbbec/451792/auto_convert.pdf

- 1 The Presbyterian way of life in nineteenth-century New Zealand Dr Alison Clarke ali.clarke@xtra.co.nz Paper presented to the P, accessed on August 27, 2025, https://www.presbyterian.org.nz/archives/presresnetworkoct09.pdf

- Religion and society | Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand, accessed on August 27, 2025, https://teara.govt.nz/en/religion-and-society

- EVANGELISM and REVIVALS in AUSTRALIA 1880 to 1914 (First Volume) by Robert Evans with a Foreword by the Rev. Dr. Dean Drayton, accessed on August 27, 2025, https://revivalsresearch.net/docs/EvangelicalismAndRevivalsInAustralia1800-1914.pdf

- EVANGELISM and REVIVALS in AUSTRALIA 1880 to 1914 (First Volume) by Robert Evans with a Foreword by the Rev. Dr. Dean Drayton, accessed on August 27, 2025, https://www.revivalsresearch.net/docs/EvangelicalismAndRevivalsInAustralia1800-1914.pdf

- EARLY EVANGELICAL REVIVALS IN AUSTRALIA This Book is available through Koorong Bookstores for $55. The author, Robert Evans, accessed on August 27, 2025, https://www.chr.org.au/books/17.-Early-Evangelical-Revivals-in-Australia.pdf

- Religion and society | Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand, accessed on August 27, 2025, https://teara.govt.nz/en/religion-and-society/print

- Trends in Religious History in New Zealand: From Institutional to Social History – Abuse in Care – Royal Commission of Inquiry, accessed on August 27, 2025, https://www.abuseincare.org.nz/__data/assets/pdf_file/0015/28014/lineham-pj-trends-in-religious-history-in-new-zealand-from-institutional-to-social-history-history-compass-124-2014.pdf

- Culture of New Zealand – Wikipedia, accessed on August 27, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Culture_of_New_Zealand

- Christianity in Australia – Wikipedia, accessed on August 27, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christianity_in_Australia

- Missions, stations and reserves | AIATSIS corporate website, accessed on August 27, 2025,https://aiatsis.gov.au/explore/missions-stations-and-reserves

- Freedom of religion, belief, and indigenous spirituality practice and cultural rights, accessed on August 27, 2025, https://humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/content/frb/papers/Indigenous%20Spirituality%20FINAL%20May%202011.pdf

- “That we may obtain our religious liberty…”: Aboriginal Women, Faith and Rights in Early Twentieth Century Victoria, Australia* – Journal of the Canadian Historical Association / Revue de la Société historique du Canada – Érudit, accessed on August 27, 2025, https://www.erudit.org/fr/revues/jcha/2008-v19-n2-jcha3329/037747ar/

- The Character of Evangelism in Colonial Melbourne: Activism, Initiative, and Leadership – Macquarie University Research Data Repository, accessed on August 27, 2025, https://figshare.mq.edu.au/articles/thesis/The_character_of_evangelism_in_Colonial_Melbourne_activism_initiative_and_leadership/19438739/1/files/34537025.pdf

- The Big Melbourne Revival – Vision Christian Media, accessed on August 27, 2025, https://vision.org.au/read/articles/the-big-melbourne-revival/

- Early Twentieth Century Revivals: Worldwide Revivals – Renewal …, accessed on August 27, 2025, https://renewaljournal.com/2014/04/28/early-twentieth-century-revivals-worldwide-revivals/

- Revival In Melbourne! – Christian History Research, accessed on August 27, 2025, https://www.chr.org.au/documents/Melbourne-Revival.pdf

- The First Global Revivalist? Reuben Archer Torrey and the 1902 Evangelistic Campaign in Australia | Church History – Cambridge University Press, accessed on August 27, 2025, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/church-history/article/first-global-revivalist-reuben-archer-torrey-and-the-1902-evangelistic-campaign-in-australia/0ED34E5D6A2B8A9AB21322AF40EE9B14

- Lessons from the Melbourne Revival (1902): An Interview with Rob Nyhuis – Kindle Afresh, accessed on August 27, 2025, https://kennethberding.com/2025/03/09/lessons-from-the-melbourne-revival-1902-an-interview-with-rob-nyhuis/

- The Ten Greatest Revivals Ever: from Pentecost to the Present – Christian Leaders, accessed on August 27, 2025, https://christianleaders.org/mod/resource/view.php?id=33487

- Controversial Revival, Part I – Global Awakening, accessed on August 27, 2025, https://globalawakening.com/controversial-revival-part-i/

- EVANGELICAL REVIVALS IN NEW ZEALAND, accessed on August 27, 2025, https://revivalsresearch.net/docs/EvangelicalRevivalsInNewZealand.pdf

- Methodist Church | Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand, accessed on August 27, 2025, https://teara.govt.nz/en/methodist-church/print

- The Salvation Army in Australia – Wikipedia, accessed on August 27, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Salvation_Army_in_Australia

- Christianity for Australia – evangelism in 1902 & 1959 – Renewal Journal, accessed on August 27, 2025, https://renewaljournal.com/2019/10/14/christianity-for-australia-evangelism-in-1902-1959/

- Studies in Australian Christianity, accessed on August 27, 2025, https://www.chr.org.au/documents/4.-Re-visioning-Australian-Colonial/Stuart-Piggin.pdf

- Presbyterian Church | Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand, accessed on August 27, 2025, https://teara.govt.nz/en/presbyterian-church/print

- 19th Century NZ – Roxborogh.com, accessed on August 27, 2025, http://roxborogh.com/REFORMED/19th_century_nz.htm

- Presbyterian Church of Aotearoa New Zealand – Wikipedia, accessed on August 27, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Presbyterian_Church_of_Aotearoa_New_Zealand

- Methodism arrives split into denominations in South Australia; grows …, accessed on August 27, 2025, https://adelaideaz.com/articles/methodism-arrives-divided-into-denominations-in-south-australia–expands–unites-and-evolves-in-social-concerns

- Methodist Church – SA History Hub, accessed on August 27, 2025, https://sahistoryhub.history.sa.gov.au/organisations/methodist-church/

- Australia – DMBI: A Dictionary of Methodism in Britain and Ireland, accessed on August 27, 2025, https://dmbi.online/index.php?do=app.entry&id=104

- Australian Student Christian Movement – Entry – eMelbourne – The Encyclopedia of Melbourne Online, accessed on August 27, 2025, https://www.emelbourne.net.au/biogs/EM00134b.htm

- Australian Student Christian Movement – Wikipedia, accessed on August 27, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Australian_Student_Christian_Movement

- en.wikipedia.org, accessed on August 27, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Australian_Student_Christian_Movement#:~:text=Originally%20named%20the%20Australian%20Student,considered%20to%20have%20inaugurated%20the

- Women and the vote – NZ History, accessed on August 27, 2025, https://nzhistory.govt.nz/politics/womens-suffrage/brief-history

- Women’s suffrage in New Zealand – Wikipedia, accessed on August 27, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Women%27s_suffrage_in_New_Zealand

- Women’s movement | Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand, accessed on August 27, 2025, https://teara.govt.nz/en/womens-movement/print

- Women’s Suffrage in Aotearoa New Zealand, accessed on August 27, 2025, https://www.women.govt.nz/about-us/history-womens-suffrage-aotearoa-new-zealand

- 1890 to 1900 – Towards Federation – NSW Parliament, accessed on August 27, 2025, https://www.parliament.nsw.gov.au/about/Pages/1890-to-1900-Towards-Federation.aspx

- Womens Suffrage in Australia, accessed on August 27, 2025, https://www.aph.gov.au/Visit_Parliament/Art/Stories_and_Histories/Womens_Suffrage_in_Australia

- History of Australia (1901–1945) – Wikipedia, accessed on August 27, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Australia_(1901%E2%80%931945

- Regional Issue: Social Policy Developments in Australia and New Zealand – PMC, accessed on August 27, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3886295/

- New Zealand identity, accessed on August 27, 2025, https://teara.govt.nz/en/new-zealand-identity/print

- Governments, Parliaments and Parties (New Zealand) – 1914-1918 Online, accessed on August 27, 2025, https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/governments-parliaments-and-parties-new-zealand/

- 6th Great Awakening 1900 – Revival Library, accessed on August 27, 2025, https://revival-library.org/timelines/1900-6th-great-awakening/

- The Ten Greatest Revivals Ever – Liberty University, accessed on August 27, 2025, https://facultyshare.liberty.edu/files/40262823/The%20Ten%20Greatest%20Revivals%20Ever.pdf

- English Christianity and the Australian Colonies, 1788–1860 | The Journal of Ecclesiastical History | Cambridge Core, accessed on August 27, 2025, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-ecclesiastical-history/article/english-christianity-and-the-australian-colonies-17881860/60C3917AEC39ED9F0321D780F74B8708

- Australian revivals Archives – Renewal Journal, accessed on August 27, 2025, https://renewaljournal.com/tag/australian-revivals/