The Ulster Revival 1859

The Ulster Revival by William Henry Harding

William Harding wrote a number of books on revivalists including Brownlow North, Charles Finney, William Burns and Robert Murray M’Cheyne. This short, but thrilling account, just a sixteen-page pamphlet on the 1859 awakening in Ireland, is a very rare work housed at the Revival Library. It is number three in series of seventeen Harding wrote on various revivalists and is undated, though probably written between 1920 and 1930. We have included the entire booklet.

Chapter I. The Fountains of the Ulster Revival

THE spiritual awakening which rendered the year 1859 for ever illustrious in the annals of Ulster, also furnishes one of the most remarkable illustrations in all history, of Christianity suddenly and potently revived and exercising a transforming influence, swift in its action and wide in its sphere, upon all classes of society.

Who were the people among whom this astonishing movement broke out? Coming of Scottish and English extraction, the Protestant communities of Ulster represent a colony, founded with infinite industry and skill, which has stood through centuries in enlightening contrast to the blighting conditions which obtain in other parts of Ireland under the domination of the priest.

The history of Ulster is of a people not only distinguished by industrial ability and commercial integrity, but also possessing strong religious proclivities, and contending earnestly in defence of Christian beliefs and Christian liberty.

The Revival led to the reclamation and conversion of vast numbers of people of careless or debased life; but primarily it meant the kindling afresh of apostolic zeal and enthusiasm, the setting up of magnificent ideals regarding the extension of the Kingdom of God throughout the world, and, first and last, the reassertion on a majestic scale of the great basal verities of Evangelical religion.

No world-famous name is associated with the Revival. Nevertheless, beginning in the prayer meetings and wayside conversations of a few humble work-people, it speedily attained the proportions of a national movement.

Various springs from the hills of Antrim contributed to swell the meandering rivulet of Revival into a broad and mighty stream. Moreover, the news of the American Awakening of 1857-8 assuredly created a spirit of hope and expectation, as people read of ministers, who had toiled with scant success for many a year, suddenly finding their churches crammed with eager listeners, and their houses besieged by anxious inquirers; of twelve thousand business men assembling day by day for prayer in New York alone.

At several places in Antrim, prayer-meetings had been held, displaying signs of deepening interest, but a careful examination brings into prominence as the chief fountain of the Revival, the visit of a Christian lady, Mrs. Colville, of Gateshead, to the town and neighbourhood of Ballymena.

Mrs. Colville, who held clear-cut views on the subject of Conversion, and was gifted with the spiritual faculty of speaking the truth in love, laboured with courage and faith to lead people to Christ. In the course of visitation and tract distribution she was brought into contact with all classes of the community; nevertheless, she was meeting with small encouragement.

At this time there was employed in one of the important industrial businesses of the district, a young man named Jeremiah McQuilken, who one day overheard Mrs. Colvile talking to a certain lady who took more pleasure in doctrinal discussions on Predestination than in vital, personal Christianity. “My dear,” said Mrs. Colville, anxious to direct the conversation into a profitable channel, “you have never known the Lord Jesus.” Whatever may have been their effect upon the lady the words went as an arrow to McQuilken’s heart.

He was smitten with the thought that, professing Christian as he was, this truth applied to him. For two weeks he had no peace, day or night. Then he found it, in Christ. His first convert was a friend named Jeremiah Meneely, and these two began to meet for prayer, with two other young men, John Wallace and Robert Carlisle. These four commenced, in a little schoolhouse at Kells, Antrim, a Believers’ Fellowship Meeting. Month after month passed and kindred spirits joined them in intercession, as they wrestled and prevailed.

McQuilken had been carefully studying the Bible, and was also much helped by a record of the life and labours of George Müller. In 1858, there were remarkable conversions. Steadily converts multiplied, and Rev. J. H. Moore, minister of the Presbyterian congregation at Connor, gave every encouragement, conducting countless services.

The Revival flame began to kindle. People were crying for mercy in open-air meetings. A singing-class was turned into a prayer meeting, and many met to pray, on occasion, all night. Public attention being aroused, Mr. Moore was requested at the General Assembly of his denomination, in 1858, to give his brethren an account of the novel and fascinating events.

It was with extraordinary fervour that the movement spread into Ahoghill and other parishes. In barns, schools, and private houses meetings were conducted and addressed by converts, and were attended by multitudes of people. At Ballymena, the whole town seemed suddenly to arouse.

“The difficulty used to be to get the people into the church,” wrote a minister, “but the difficulty now is to get them out.” The benediction would be pronounced again and again, but each time the irrepressible petitions of the praying people would burst forth afresh, or the cry of the penitent, mourning over sin, would break upon the ear, and so the meeting would of necessity be protracted—perhaps into the early hours of the morning.

Within the bounds of the Connor congregation a hundred prayer meetings were held every week. The blasphemies of parties returning from markets, which had become a public nuisance, gave place to such simple but expressive hymns as the famous “What’s the News?” —

Whene’er we meet you always say:

‘‘What’s the news? What’s the news?

Pray what’s the order of the day,

What’s the news? What’s the news?”

Oh, I have got good news to tell,

My Saviour hath done all things well,

And triumphed over death and hell—

That’s the news, that’s the news!

The insensate ditties of music hall and theatre were entirely eclipsed by “What’s the News?” Mr. W. Hind Smith, of the Y.M.C.A., who visited Ulster at the time, said, recalling its extraordinary popularity: “Wherever I went I heard ‘What’s the News?’ Everybody, it seemed, sang it. If you purchased a railway ticket you would hear the booking clerk singing: —

‘The Saviour died on Calvary,

That’s the news, that’s the news.’

Or if you asked a policeman the way, you would hear him commence, after he had directed you, as he continued upon his beat: —

‘His work’s reviving all around,

That’s the news!’

The astonishing character of the spiritual revolution wrought in Ballymena is demonstrated by the testimony of Rev. S. Moore, who said:

“On my return, after two days’ absence at a Meeting of Synod, I found the town in a state of great excitement. Many families had not gone to bed for two or three nights. From dozens of houses, night and day, you would hear, when passing along, loud cries for mercy from those under conviction, or the voice of prayer by kind visitors, or the sweet, soothing tones of sacred song. Business seemed at a standstill.

In some streets, crowds of people, in the houses and before the open doors and open windows, engaged in prayer or praise, all at the same time. A goodly number of young men in business establishments in the town, and not a few workmen, who were dependent upon their daily wages for their daily bread, gave up almost their whole time to the religious instruction and physical and spiritual comfort of the poor stricken sufferers [i.e., those who were prostrate under an intense realization of their sinful state].

Persons from England and Scotland and many parts of Ireland were to be seen perambulating the streets and lanes of Ballymena—ministers, missionaries, Sabbath School teachers, and cool, inquisitive business men, anxious to witness, with their own eyes, this strange thing of which they had heard in their distant homes

—a half-dead soul revived by God’s Spirit, a poor, lost sinner (his crimes hanging over him like a heavy cloud, and his heart sore pained within him, fearfulness and trembling and honour overwhelming him) pleading for mercy.”

Chapter II. A Social Transformation

Although the churches and other meeting-places were crowded, the Revival was marked by such heart-stirrings that even large buildings were not able to contain the multitudes that assembled. Hence, meetings were held on the highways, in the fields, or at any popular rallying point.

A Belfast visitor, invited to speak at the village of Broughshane, found his congregation to consist of about five thousand people, the meeting-place being a quarry. The great assembly listened with close attention, particularly to a noted character— “an old man, remarkable looking—; a dealer in rags would not have given more than sixpence for all the clothes he had on his person; he bore the marks and tokens of a confirmed drunkard.” Tremblingly, this aged brother gave his earnest testimony: —

“Gentlemen, I appear before you this day as a vile sinner. Many of you know me, for you have but to look at me and recognize the profligate of Broughshane; you know I was an old man hardened in sin; you know that I was a servant of the devil, and he led me by that instrument of his, the spirit of the barley. I brought my wife and family to beggary more than fifty years ago; in short, I defy the townland of Broughshane to produce my equal in profligacy, or any sin whatever; but gentlemen, I have seen Jesus!

I was born again on last night week, and am therefore ‘a week old’ to day. My heavy and enormous sin is all gone, the Lord Jesus took it all away, and I stand before you this day not as a pattern of profligacy, but a monument of the perfect grace of God. “I stand here to tell you that God’s work on Calvary is “perfect.

Yes, I have proved it His work is perfect. He is not like an architect who makes a drawing of a building, and then takes out this line or that, or alters “the whole, and even while the building is going up makes some further change. No, but God drew out the plan of salvation, and it was complete, and He carried it out with His blessed Son Jesus, and it is all perfect, for had it not been so, it would not have been capable of reaching the depth of iniquity of myself, the profligate of Broughshane.”

In the Broughshane district, within an area of more than two miles, almost all the mothers of families were converted they held prayer meetings together and exercised a mighty influence. Two public houses were closed. The Bible became the book of constant study, and the young men in the churches gave splendid help to the ministers.

On Fair Day, when a band of strolling performers made their appearance, a prayer meeting was immediately commenced opposite their platform, so that the players were left with a total audience of two policemen—both of whom were Roman Catholics. A day so admirably begun could have only one appropriate conclusion; the Fair terminated with a Gospel meeting, attended by five thousand people.

Inevitably, not a few Roman Catholics were brought under the influences that were so powerful in the country, and many were converted. The priesthood became alarmed, all the more keenly because they had to contend, not only with the loving presentation of Gospel truth, but in an atmosphere of intense delight in saving grace. They could meet polemic with polemic, but the consistent life and witness of a host of lowly believers could be neither gainsaid nor attacked with any hope of success.

The Revival was sometimes described by them as “a satanic delusion,” but this was sufficiently met by the comment of one who attended an “altar lecture” on the subject: “If it is the devil who has done it, then there must be a new devil, for I’m sure “the ould wan woaldn’t do it at all, at all.” It was shrewdly remarked too, by a convert, in addressing a congregation, “certainly it was not Satan who took me away from “whisky drinking.”

At Ahoghill, in a public meeting called purposely to afford the people an opportunity to acquire information regarding the Revival, it was anticipated that some converts would speak, and the expectation was sufficient to draw, to the first Presbyterian church, so great a congregation that it was feared the galleries would collapse.

The minister accordingly pleaded, for the sake of safety, that the place should be vacated, but the ardour of the people knew no daunting deeply stirred, they assembled again in Ahoghill Square, which was filled with people. From the steps of a dwelling house, one of the converts addressed the crowd —of about three thousand.

Rain was falling heavily, and the street was muddy, yet, as the touching words of the unknown orator fell upon receptive minds, old men wept and the young were awed and subdued. The meeting continued till a late hour, and even in that miry thoroughfare the anxious knelt and cried to God for mercy.

The neighbourhood, like many others, became transformed. Young men who had been noted as idle vagabonds were seen exhorting the careless. The Presbytery, having sent a deputation to examine the work, recorded the testimony that drunkenness and Sabbath-breaking, blasphemy and profane language and neglect of the great salvation had been all but annihilated.

This, of a village which a police-officer, who had once been stationed there, described to Rev. William Arthur, the distinguished Methodist preacher and author, as “the worst wee place in the world,” and where drunkenness, fighting and swearing had been so prevalent that on special occasions, such as a “funeral day,” the lack-up was invariably full.

Chapter III. The Thirst After Righteousness

The Revival spread over Antrim and Down, and everywhere with the same signs of a deep work of the Spirit. The testimony of the Hon. and Rev. Henry Ward, rector of Killinchy, co. Down, has special weight, for Mr. Ward had laboured among the people for thirty years. “The spirit of our meetings,” he declared, “is all harmony and love.

The labour being divided between the ministers of the two denominations (Episcopal and Presbyterian] no distinction is made, but the hearts of all are knit together in one holy bond of Christian fellowship. There is no exaltation of man or means, no novelty, no unnatural excitement. There can be no imposition practised; such a thing, from the deep seriousness, which pervades this part of the country at the present time, would not be tolerated by the people.

That the work, so far as it has come under my observation, is the work of God. I have no more doubt than of the truth of the Philippian jailer’s conversion.”

So intense was the desire after the things of God that it was recorded of one district: “Whole townlands are awakened, all outdoor labour suspended, and the people in crowds follow the minister from door to door, to engage in prayer.”

The Earl of Roden, whose testimony was that of a landlord moving in and out on the friendliest terms among the tenantry, bore witness to the effects of this great Revival, declaring that the public-houses were deserted, solemnity pervaded the population, and prayer-meetings in many houses of the most respectable farmers were attended by the neighbours in great numbers.

This solemnity of feeling was everywhere observable. For example, at Crossroads, near Omagh, a meeting in a Presbyterian church was described as “truly astonishing and awful,” as cries for mercy and salvation rang through the building. Literally for hours neither singing nor audible congregational prayer could be conducted, every heart being so subdued; nor did the meeting close until near the break of day.

Again, at Kilmacrennan, after the devotional exercises of the Sabbath morning service were concluded, cries of mercy suddenly arose from various parts of the congregation. The persons affected were led to the entrance hall, to the schoolhouses, or out on to the church green; the friends of each assembled round them. Thus, the entire premises were given to many lesser congregations, engaged in prayer and praise. Public worship could not be proceeded with until late in the afternoon; and night after night the good work went on.

Such conditions prevailed, not merely in isolated spots or patches of country around some specially affected town, but they were general throughout Ulster. MuItitudes thronged the house of prayer. Ministers were fetched from their work of visitation to conduct services in churches crowded with people. As the Gospel was proclaimed and the Atoning Work of Christ described, piercing cries would rise from the anguish-stricken “Oh, my sins, my sins!”

Then the regular order of procedure would be of necessity suspended. Groups of Christians gathered round the anxious, engaging in prayer, or quoting Scripture consolation regarding the Balm of Gilead. Godly leaders spoke of Calvary and the precious blood of Christ, in terms of loving faithfulness such as Bunyan might have used among Bedfordshire villagers, or Grimshaw to the lowly folk of the Yorkshire moors.

Such were the scenes, which were to be witnessed from Down to Donegal. Yet they illustrate, but inadequately the depth and extent of the Awakening, as, escaping from the overwhelming sense of guilt by casting the heavy load at the feet of the Burden-bearer, weary ones found peace ineffable, and began to speak in the liberty of the Spirit.

Recording some “crowded hours of glorious life,” Rev. Hugh Hunter, of Bellaghy, co. Derry, wrote to Dr. Massie (Secretary of the Irish Evangelical Society): “It pleased the Lord to visit us with such a superabundance of spiritual blessing as I cannot attempt to describe. I was not in bed during the first week a single night. Each morning I got a sort of dreamy doze, but I could not actually sleep, for each morning my house was full of anxious souls waiting for a word of Bible consolation.

Before this, our day of merciful visitation, Bellaghy was the most degraded of Irish villages. Rioting and drunkenness were the order of each evening. Profane swearing and Sabbath desecration were most fashionable sins, and such a place for lying and stealing I do not know. Many a time I longed to get out of it. Well, we have a change now that is truly gratifying. As you pass down the street you hear, in almost every house, the voice of joy and melody.

Stop in the way; name the Name of Jesus, and old and young crowd around you. Raise the voice in praise or prayer and every dwelling pours out its inmates to join the company of anxious hearers. Those who heretofore were at ease in Zion, now tremble as in the presence of God. A minister from a distance heard of the Lord’s work in Bellaghy. He could not credit the extraordinary accounts.

He came, he saw—Jesus conquered him. As I was conveying him out of the village, he exclaimed, as the holy sounds reached his ears from the humble dwellings of the poor: ‘I feel as if I were breathing the atmosphere and treading the golden streets of the New Jerusalem.’”

Of all the stories of Revival blessing, none is more striking than that of Coleraine. The movement first became evident there in a huge assemblage of people, drawn by no alluring announcement of magnificent oratory, but simply to hear the testimony of a few rural converts, upon the Fair Hill.

It was a cloudless evening in June. Shortly after seven o’clock masses of people from town and country began to pour into the square, by every approach, and the platform which had been prepared was speedily surrounded by the multitude. Ministers of all the Protestant denominations were present, and when it was found that no voice could range to the confines of so vast a crowd, they and the converts took up various stations on the Hill, each group immediately securing its own large auditory.

Then, as the Gospel was preached, many convicted souls sought refuge in Christ. Again the congregations were split into smaller sections, each being grouped around earnest believers who were pointing the anxious to Him, and repeatedly, as peace came to stricken hearts, there arose, first in a gentle murmur and then in a swelling anthem, the familiar paraphrase of the Fortieth Psalm: —

He took me from a fearful pit

And from the miry clay,

And on a rock He set my feet,

Establishing my way.

Next day the town experienced the growing force of the Revival. Those who were experimentally able to serve as Greathearts to pilgrims, were engaged unceasingly in such hallowed ministry. Soon, every street in the town numbered its converts.

In those Revival days, no false shame hindered the repentant sinner from expressing, with all naturalness, his actual feelings; hence, stricken with remorse, men and women, whether respectable churchgoers or of flagrant life, sought the Saviour, with agonizing cries which were an indication, not of any mental fantasy, but of a profound realization of spiritual need.

At this time, the new Town Hall, a fine building costing nearly £7,000, was ready for formal opening, and the method of inauguration had been a subject of discussion, some proposing a ball. The waltz, however, had now less interest than the story of Redeeming love, and the temper of the town was not toward the polka. When, therefore, another vast meeting was held in the market place, and when on every hand the anxious were crying for mercy, so that the moans and cries reminded the hearer of a field of battle, it was suggested that the stricken ones should be gathered, for spiritual help, into the Town Hall. To that convenient shelter, accordingly, the people proceeded. Thus, the building was consecrated by the tears and prayers of penitent sinners, as all night long, the gracious work went on.

The meetings were at once continued in the Independent Chapel, which was crowded to overflowing. When the first congregation was in due course dismissed, the building was immediately filled by another, and again, again, and again, as the service was terminated, fresh and eager crowds pressed in. At length the ministers were obliged to conclude, but when they left the building it was only to commence in another way, for they were again up all night praying with seekers after Christ.

The Town Hall, too, was again opened and remained so until five o’clock in the morning, the people being unwilling to leave, even then. Subsequently, a minister who left the chapel for a few minutes “to get a breath of fresh air,” noticed a number of people running. On making inquiry he found that they were proceeding to the School of the Irish Evangelical Society; going with them he witnessed an affecting scene, for:

“There, on their knees, were one hundred children, and beside them, ladies and gentlemen of position, who had been ‘too genteel’ to attend the extraordinary meetings, or who had been prevented by delicate health, prostrated together before the Throne of Grace. The godless and worldly-minded man of business was there; old and young of the higher classes were there, all crying out for grace and pardon.”

Chapter IV. National Interest in the Revival

From county to county still the movement spread. Of a scene at Newton Limavady, an eye-witness said: “In a field, in front of my own house, an immense work of God, and that in wonderful power, was presented to the astonished eyes and hearts of a vast concourse of beholders. Not fewer than a hundred souls were brought under conviction of sin.

Some of the women and children were conveyed into the house; others followed to assist them; and shortly, nearly every room in the house was crowded with persons crying out and praying for mercy. The lawn was literally strewed like a battle-field with deeply wounded ones under conviction of sin by the Holy Spirit, who was revealing Christ to their souls.”

The field meetings and huge gatherings in public places were, indeed, a conspicuous feature, inevitably so on account of the insufficiency of public buildings to accommodate such abnormally large crowds. At Ballyclare two thousand people assembled in the grounds of the Presbyterian Church, many being attracted by the news of wonderful conversions, and so crowded did the church itself become with seekers after God and those who sought to minister to such, that the doors had to be closed.

This was but one meeting of many; small wonder, then, that all the public houses were empty; there was a prayer meeting in almost every second house. It was quite customary at Ballyclare for meetings to be attended by thousands.

On Dunmull Hill, near Bushmills, Brownlow North and a couple of converts from Connor addressed a crowd of seven thousand persons. When the meeting was supposed to terminate, the people were still so eager that North gave a second address, and throughout the meeting people were stricken down under a sense of sin. It must not be supposed that these great field services and open-air prayer meetings were in the nature of mere religious picnics: on the contrary, the deepest earnestness prevailed.

At Londonderry a united prayer meeting was held daily, attended by from four to five thousand persons. Evangelical ministers each conducted five services each day, in addition to visiting the anxious and fulfilling other and multifarious duties, incidental to a period of profound religious concern. Open-air meetings, attended by vast crowds, were frequent; hour after hour would pass in exhortation and prayer, and when adjournment was eventually made to the churches, the crowds would cram the buildings and overflow into the school-rooms. “Let me never fancy “I have zeal,” said Henry Martyn, facing the actualities of heathen fanaticism and official blindness, “until my heart overflows with love to every human being.” Something of that spirit of this universal compulsion of souls, obtained in Derry; the spirit-shrivelling frivolities of the world found their false light quenched in the rising splendour of the Sun of Righteousness. Among all classes there was unparalleled anxiety of heart. In less than six weeks, one minister, apart from other work, conversed with about three hundred people who were under deep conviction, and most of them found peace. In the outlying districts as well as in Derry itself, the Revival changed the entire social conditions. When a party of strolling players, ochred and rouged, arrived on their annual visit to a village where they were wont to realize a considerable sum of money, they at once fled in dismay, for they found themselves faced by an audience of one person only.

Scenes equally remarkable were witnessed in Belfast itself. Nearly every street numbered its penitents. Perhaps the most remarkable meeting in point of numbers was that held in the Botanic Gardens, when at least twenty thousand people attended, people of staid demeanour and earnest behaviour, carrying Bibles and hymnbooks.

Throughout the city ministers and laymen were alike engaged in going from house to house, visiting and praying; during these exercises hundreds who, in agony of mind, had left the public meetings, were led into rest. An eye-witness recorded how he “stood for an hour and a quarter, on a Saturday evening, in a crowd, computed at five thousand people, who were listening with breathless attention to a sermon by Henry Grattan Guinness, on ‘Many waters cannot quench love.’”

In churches where it was a rare thing for any to kneel all would be bowed humbly, while cries would be heard from every part of the building: “God be merciful

To me a sinner.”

The sterling worth of the Revival was ere long put to a public test, when a writer in a Roman Catholic paper (published in Dublin) declared that he would accept the movement as Divine if the Boyne Celebration passed without a party procession in the Durham Street district, a Belfast neighbourhood notorious for party animosities which often culminated in rioting and bloodshed.

The outcome supplied splendid evidence of the vital power of the Revival. So thoroughgoing was the change wrought in Durham Street, under the tender influences of the Gospel, that drunkenness and ribaldry gave place to prayer and praise, and on the eventful Twelfth of July there was not so much as a party badge to be seen; no drum thundered; no provocative cry was heard.

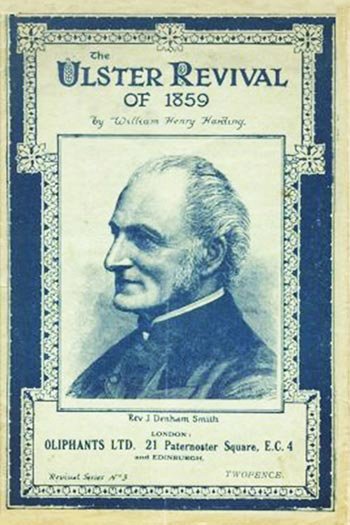

Even in the dark regions of the south and west—dark because under the sway of the priest—there were springings of the water of life. Under the daily preaching of Grattan Guinness great numbers were impressed at Limerick. There were many conversions in county Carlow, under the preaching of Joseph Denham Smith: indeed wherever that gifted and gracious evangelist went, his words distilled in blessing.

Chiefly, however, Denham Smith’s name is associated with the movement in Dublin. After visiting Ballymena, in order to study the Revival, he returned to his ministry at Kingstown, full of a new fervour, and at once an extraordinary awakening took place, thousands of people turning to Christ. On the Metropolitan Hall being taken, still greater numbers flocked to hear, and often remained hour after hour, so that the meetings were continued until late at night.

One result of the Kingstown work was the conversion of almost the whole of the crews of the four steamboats crossing the Irish Channel. Meetings for praise and prayer were held by the sailors whenever they were in harbour, and when the cabins proved too small, preaching was commenced from the deck of one or another of the boats moored along the quay, on Sunday afternoons, so that “some of the scenes on the shore of the Lake of Galilee were reproduced in the harbour of Kingstown”

Ultimately, it was decided to erect in Dublin a capacious hall in which Denham Smith should find a convenient centre for the prosecution of the special work of evangelism for which he was so conspicuously endowed. Accordingly the Merrion Memorial Hall was erected—one more permanent outcome of the Revival.

A distinguished French visitor, who went to Ireland “full of distrust,” declared of the Revival: “This is a mighty work of God.” There was indeed no other conclusion that could be sustained.

The Presbyterian Church of Ireland, fifty years after, testified in solemn and moving terms to the grandeur and greatness of the movement, acknowledging a very large accession to the membership, reckoned by many thousands, an overflowing stream of candidates for the ministry, a development of Church extension, the creation of a new spirit of Christian liberality, and a Forward Movement in Home and Foreign Missionary enterprise. Such was the well-weighed verdict pronounced after the lapse of half a century.

Summing up the general characteristics of the movement it must be said….

1. The Revival was a work of the Spirit. It had its origin in profound conviction of sin, manifested in vast numbers of people who were further led to find rest in the Lord Jesus Christ. The Hon. and Rev. Baptist Noel, one of the most earnest and spiritually minded ministers of his time, computed that there were a hundred thousand converts. Beyond these, of course, there were multitudes who, although not new creatures in Christ Jesus,” at least reformed their ways of life.

2. It made for Temperance. “It is impossible not to observe,” said the Dowager Countess of Londonderry, “that one result of the much-talked-of Revival has been the closing of public-houses and the establishment of greater sobriety and temperance.” Mr. Macartney, a Justice of the Peace and at one time Member of Parliament for Antrim, witnessed that in certain parishes the use of ardent spirits was almost entirely abandoned.

3. It worked a miraculous change in manners. Rev. William Arthur, noting how the Boyne anniversary passed in a peaceful way that astonished the most sanguine, described the effect as “the most striking effect produced upon national manners, in our day, in these islands, by the sudden influence of religion. I saw people coming away quietly, in streams, from a fair, where before they would have been reeling by dozens.

I heard masters tell of the change in their men, boys of that in their comrades; I heard gentlemen, doctors, merchants, shop-keepers, tailors, butchers, weavers, stone-breakers, dwell with wonder on the improvement going on among their neighbours. I knew the people and I believed my own eyes.”

4. It called forth the sacrifice of praise. The General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church appointed a day for prayer and thanksgiving to Almighty God for His “gracious mercy vouchsafed in the revival of religion.” Joy in God was exultant; there was an earnest desire after holiness of life; millions of hymnbooks were sold.

5. It was a work wrought largely through humble and local means. Hundreds of the men and women who exhorted and prayed and visited with such ardent love for God and souls were mill-hands, porters, shopmen, ploughmen and the like. Their ordination was that of “the pierced hands”; their testimony was in the power of the Spirit; their burning zeal—itself a prime characteristic of Revival, had no touch of petulance or pride or self-assertion. Their warnings were in the spirit of Him who wept over the city that knew not the hour of its visitation. He brought me up also out of the horrible pit, out of the miry clay, and set my feet upon a rock; this was the keynote of all their plainspoken words.

6. It made for unity. Evangelical believers were at one, brotherly love prevailed, and love and zeal transcended every ignoble thought of denominational aggrandisement. “The great things of the Revival,” said Dr. Massie, “did not concern the polity of the Churches, but the peace of a sinner with his God.”

Assuredly, if solemnity of mind, contrition for sin, tenderness of conscience, love towards God, a yearning to do His will, and an intense missionary spirit that goes out to all the world, are characteristics of the Divine conquest of the soul of man, then the Ulster Revival was truly a work of the Holy Spirit.

A few solitary veterans, the remnant of the godly men who bore the burden of the day, still answer to the roll-call, with indomitable spirit if with feeble voice; they still delight to recall the fragrance, as of the garden of God, which arose as the winds of heaven blew upon the land; and if to our duller ears their words sound strange and mystic, as of music from the higher spheres, the fault is ours, since Christ is none the less the Mighty to Save, nor is our God less willing than in 1859 to hear the cry of His people.

For further research:

The Year of Grace William Gibson