1857-1859 Great Canadian Revival

Phoebe Palmer

Introduction

The Great Canadian Revival of 1857-1859 was a complex, multi-regional spiritual awakening deeply connected to the transatlantic “Layman’s Prayer Revival.” It was not an isolated event but a movement catalysed by widespread socio-economic anxiety and a pre-existing climate of “holy discontent.” While the revival produced significant church growth, empowered new forms of lay and female ministry, and left a lasting institutional legacy, it also helped consolidate an Anglo-Protestant cultural hegemony with profound and often paradoxical consequences for the developing nation. This period of intense religious fervour represents a pivotal moment in Canadian history, where international spiritual currents and unique local conditions converged to reshape the country’s Protestant landscape on the eve of Confederation.

This analysis examines the revival’s causes, key figures, denominational dynamics, and its immediate and long-term impacts, situating the Canadian experience within its broader North American context to offer a nuanced understanding of how a movement of personal spiritual renewal both reflected and shaped the character of a nation in formation.

The Tilled Soil: Canada on the Eve of Revival

The spiritual eruption of 1857 was the product of a society undergoing profound and unsettling transformations. The economic, social, and religious conditions of British North America in the mid-19th century created fertile ground for a widespread popular religious movement.

A Nation in Transition

By the 1850s, the economy of the Province of Canada was shifting from a reliance on timber to one more dependent on agriculture, particularly wheat. This transition was engineered through massive public investment in infrastructure, with 1,900 miles of railway constructed between 1853 and 1860, opening the hinterlands of Canada West (Ontario) and Canada East (Quebec) to commercial agriculture. This era also marked the dawn of Canadian industrialization. Urban centres like Hamilton, Toronto, and Montreal saw the rise of manufacturing, which, along with immigration, fuelled rapid urbanization and created new social challenges, including poverty and labour tensions.

The social structure was also in flux. The abolition of the seigneurial system in 1854 symbolized the decline of an old landed gentry, replaced by a powerful, predominantly Anglo-Protestant merchant elite in the cities. This new class championed a myth of the “self-made man,” yet a clear social hierarchy became entrenched. While relatively prosperous, Canada’s economy was precariously balanced on volatile international demand for its staple products.

The Panic of 1857: Financial Crisis and a Climate of Desperation

This volatile prosperity was shattered in the autumn of 1857 by a global financial crisis. The Panic of 1857, triggered by the collapse of an American trust company, was the result of rampant over-speculation in railway stocks and western land. In Canada, the panic caused a stock market crash and a severe recession. Banks failed, factories closed, and unemployment skyrocketed.

The crisis was a profound psychological catalyst, creating widespread anxiety and desperation. The sudden collapse of material wealth prompted a collective questioning of worldly pursuits and turned many toward spiritual solace. The panic reached its peak in mid-October 1857, precisely when the first prayer meetings in New York and Hamilton were beginning, acting as a powerful accelerant on the nascent revival movement.

The Religious Landscape: “Holy Discontent”

Mid-19th century Canada was defined by a pervasive “Christian common sense,” where mainline denominations—Anglican, Presbyterian, and Methodist—enjoyed a privileged relationship with the state. This Protestant ascendancy fostered a climate of exclusion against Indigenous spiritual traditions and non-conforming groups.

This dynamic was codified in the Gradual Civilisation Act Gradual Civilization Act of June 1857, a law aiming to assimilate Indigenous peoples by extinguishing their legal status and cultural identity in favor of Euro-Canadian Christian norms. The revival, therefore, emerged from and reinforced a cultural environment that equated Protestant Christianity with civilization.

Within this dominant Protestant culture, however, there was a palpable sense of spiritual malaise. Many church leaders felt the evangelical fire of earlier generations had dwindled into lukewarm formalism. This “holy discontent” and a longing for revival were not new. The First Great Awakening had swept the Maritimes in the 1770s under Henry Alline, and American evangelists had held successful revivals in the 1830s. This legacy created a cultural memory and an active expectation of revival, a spiritual tinderbox awaiting a spark.

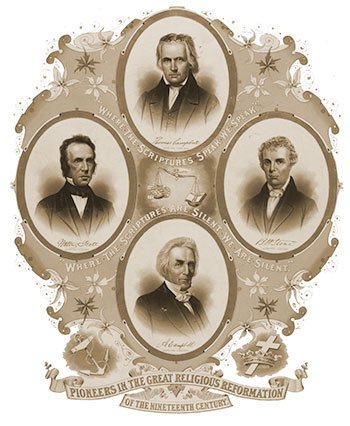

The Spark Ignites: Origins and Key Figures

The Great Canadian Revival was the northern front of a larger transatlantic movement. Its origins were shaped by charismatic leaders and varied across the regions and denominations of British North America, ignited by two powerful, nearly simultaneous engines: an urban awakening in Central Canada and a more indigenous stream of revivalism in the Maritimes.

The American “Prayer Revival”

The immediate catalyst was the “Layman’s Prayer Revival” in New York City, a movement led by laypeople, intentionally non-sectarian, and focused on prayer rather than preaching. Its origin is traced to Jeremiah Calvin Lanphier, a lay missionary who started a noonday prayer meeting for businessmen on September 23, 1857. Only six men attended the first meeting.

However, the meeting grew steadily, and as the financial panic intensified, desperate men flocked to pray. Within six months, an estimated 10,000 businessmen were gathering daily for prayer across New York City. Newspapers spread the news of the “revival” across the continent via the telegraph, creating a sense of a continent-wide movement and inspiring similar meetings elsewhere, including Canada.

Phoebe Palmer and the Hamilton Awakening

While Lanphier’s meeting was the seed, a distinct awakening erupted almost simultaneously in Hamilton, Canada West, under the formidable American Methodist evangelist, Phoebe Palmer. In October 1857, Palmer and her husband Walter were unexpectedly delayed in Hamilton. Local Methodist leaders invited them to speak, and the response was immediate. Twenty-one people professed conversion at the first meeting, and within ten days, over 400 conversions were reported.

The revival swept through the city’s four Methodist churches, with attendance swelling to 6,000 people and a total of 500 to 600 conversions, including the mayor of Hamilton.

The Hamilton revival was driven by Palmer’s dynamic preaching and her distinct Holiness theology. She preached a message of “entire sanctification”—a second work of grace that empowered believers for holy living.

Her key contribution was her “shorter way” to holiness, an accessible, three-step “altar theology”: 1) total consecration to God; 2) exercising faith that God accepts the sacrifice; and 3) publicly testifying to the experience.

This simple formula resonated powerfully with laypeople. Palmer’s ministry was also revolutionary for women. She was a powerful preacher who provided a robust theological defense for female ministry, inspiring a generation of women, including Catherine Booth, co-founder of the Salvation Army.

Isaiah Wallace and the Maritime Baptists

Concurrent to Palmer’s work, another stream of revivalism flowed through the Maritime provinces, particularly among Baptists. While historical records are more fragmented, Isaiah Wallace is positioned as a key figure in Maritime Baptist revivalism during this period. Historical analysis places Wallace as a spiritual heir to Henry Alline’s “New Light” Great Awakening of the 1770s.

Unlike the Hamilton revival, sparked by an external catalyst, revivalism in the Maritimes was an indigenous phenomenon, an “ebbing and flowing” of spiritual fervor that had characterized the region for decades. The Baptist churches were the primary carriers of this tradition. The revival of 1857-1859 in the Maritimes can thus be seen as a powerful intensification of an ongoing spiritual current, with local leaders like Isaiah Wallace serving as its conduits.

The Spreading Flame: The Revival Across Canada (1857-1859)

Once ignited in Hamilton, the revival spread with remarkable speed, its path shaped by modern infrastructure, media, and the denominational landscapes of British North America.

From Central Canada to the Atlantic

The telegraph and a burgeoning religious press broadcast news of the events in Hamilton and New York across the continent. Denominational papers like the Christian Advocate and Journal provided enthusiastic accounts that created an atmosphere of intense spiritual expectation. In August 1858, the revival’s flame was carried personally to the Maritime provinces when Walter and Phoebe Palmer embarked on a major preaching tour.

Their highly successful campaign, made possible by train and steamship, directly linked the two major streams of revival. They reported 400 conversions in St. John, 170 in Halifax, and 700 on Prince Edward Island, demonstrating how the revival followed the era’s transportation and communication networks. The revival was, however, primarily a phenomenon of the settled regions of Central and Atlantic Canada, with no evidence of it reaching the Prairie West or British Columbia.

Denominational Dynamics

The revival was primarily a Methodist and Baptist affair.

- The Methodist Church was the engine of the revival in Central Canada. Its Arminian theology, with its emphasis on free will, and its established revivalistic practices like the “altar call” and camp meetings, provided the ideal framework for the awakening.

- The Baptist Church was the primary vessel for revival in the Maritimes, building on the enduring legacy of Henry Alline’s “New Light” movement. The revival also had a powerful impact within Black communities. The First Regular Baptist Church in Dresden, Canada West, established by former slaves, held its inaugural service in its new building on November 15, 1857, as the revival gained momentum.

- The Presbyterian Church played a more responsive role, organizing conventions to discuss the need for revival and praying for its spread, but the initial impetus came from other quarters.

The revival both reinforced the existing social order, with civic leaders participating openly, and challenged it through the leadership of a woman preacher, the empowerment of the laity, and its resonance within Black communities.

The Afterglow: Immediate and Lasting Consequences

The Great Canadian Revival left an indelible mark on the nation’s religious and social fabric. Its immediate consequence was a dramatic increase in church membership, while its long-term legacy was more complex, contributing to progressive reforms while also reinforcing a dominant and problematic Protestant cultural ethos.

A Harvest of Souls

The most immediate result was a massive influx of new converts. While comprehensive Canadian statistics are lacking, local reports and U.S. data paint a clear picture. The Hamilton revival claimed 500-600 conversions, and the Palmers’ Maritime tour yielded over 1,270.

In the United States, an estimated 50,000 people were converted weekly at the revival’s peak, with a total of 500,000 to 1,000,000 new members added to Protestant churches over two years. A proportional, if smaller, surge in Canadian church membership, likely in the tens of thousands, can be inferred.

Social and Cultural Transformation

The revival empowered groups traditionally marginalized within the church. As a “laymen’s movement,” it fostered a more democratic and participatory Christianity. Phoebe Palmer’s central role provided an undeniable model of female religious leadership, challenging patriarchal norms and inspiring figures like Catherine Booth. The revival meetings themselves were noted as spaces where social barriers of class, gender, and race were temporarily erased.

This emphasis on personal transformation fueled the growth of the social Gospel movement. The revival’s focus on personal holiness extended to a desire to reform society, providing moral and popular support for causes like temperance, the abolition of slavery, and the establishment of new philanthropic organizations like the YMCA.

Institutional Legacies: A Dual Inheritance

The revival’s fervour also left a lasting institutional legacy, particularly in education. The desire to train a new generation of evangelical leaders led to the founding of new schools. A prime example is the establishment of the Canadian Literary Institute in 1857 by prominent Baptists, which was the direct forerunner of McMaster University. However, the revival’s legacy is a dual inheritance.

The very success of the movement in forging a powerful, shared evangelical identity had a darker side. This consolidation of a dominant Anglo-Protestant culture sharpened the lines between who was considered a “proper” Canadian and who was not. This cultural hegemony provided the moral justification for increasingly aggressive assimilationist policies directed at Indigenous peoples.

The passage of the Gradual Civilization Act in 1857, just before the revival, was a clear expression of this colonial ethos. The revival, by popularizing a specific vision of Christian civilization, inadvertently strengthened the cultural underpinnings of such policies. The same denominations at the forefront of the revival—Methodists, Presbyterians, Anglicans, and Baptists—would become the primary operators of the federal residential school system.

This presents a difficult paradox: a movement that brought spiritual liberation to many simultaneously contributed to a cultural climate that enabled a system of profound oppression for others.

Conclusion: Lessons from the 1857-1859 Great Canadian Revival

The Great Canadian Revival of 1857-1859 was a pivotal chapter in the nation’s history, born from a confluence of social anxiety, transatlantic religious currents, and indigenous spiritual hunger. It was a dual-engine phenomenon, sparked by the Methodist-led awakening in Hamilton under Phoebe Palmer and a concurrent Baptist revivalism in the Maritimes. Its immediate success in revitalizing church life was undeniable.

Its legacy, however, is a study in contrasts, fostering progressive social change while also consolidating an exclusionary Anglo-Protestant cultural identity. From this rich history, several beneficial takeaways can be drawn.

Enumerated Beneficial Takeaways from the 1857-1859 Revival

- The Power of Lay-Led Initiatives: The revival is a powerful testament to the fact that profound change can be initiated by ordinary people outside formal leadership structures.

- The Centrality of Prayer in Times of Crisis: The events provide a compelling case study on how societal crisis drives people to seek spiritual solace, with collective prayer serving as the primary vehicle.

- The Transformative Impact of Female Ministry: The central role of Phoebe Palmer demonstrates the transformative power unleashed when traditional gender barriers in religious life are challenged, advancing the cause of women in ministry.

- The Link Between Personal Renewal and Social Action: The revival illustrates the vital connection between individual spiritual transformation and a commitment to broader social reform, fuelling the Social Gospel movement.

- The Effectiveness of Simple, Accessible Theology: The revival’s appeal was aided by the clarity of its core message, such as Palmer’s “shorter way,” highlighting the importance of a theology that can be readily understood and practiced.

- The Unifying Force of a Common Spiritual Experience: In an era of increasing stratification, the revival created a powerful sense of unity and shared identity, forging a cohesive Protestant community that would significantly shape Canadian society.

For further research

Phoebe Palmer and the 1857 Hamilton Revival – Faith Today

https://www.faithtoday.ca/Magazines/2020-Nov-Dec/Phoebe-Palmer-and-the-1857-Hamilton-Revival

Mid-nineteenth Century Revivals: Prayer Revivals – Renewal Journal – WordPress.com https://renewaljournal.wordpress.com/2014/04/28/mid-nineteenth-revivals-prayerrevivals/

The Time for Prayer: The Third Great Awakening | Christian History Magazine https://christianhistoryinstitute.org/magazine/article/time-for-prayer

Revival Born in a Prayer Meeting – C.S. Lewis Institute

https://www.cslewisinstitute.org/resources/revival-born-in-a-prayer-meeting/

4th Great Awakening 1857 Timeline – Revival Library

https://revival-library.org/timelines/1857-4th-great-awakening/

Phoebe Palmer – WRSP

https://wrldrels.org/2016/10/08/phoebe-palmer/

Revival in the City: The Impact of American Evangelists in Canada, 1884-1914

https://www.tyndale.ca/publications/revival-in-the-city-the-impact-american-evangelists-in-canada-1884-1914

American Revivals 1859 – Revival Library

https://revival-library.org/histories/1859-american-revivals/

Third Great Awakening – Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Third_Great_Awakening

Fourth Great Awakening 1857 – Revival Library

https://revival-library.org/histories/1857-the-fourth-great-awakening/

The Awakening of 1857-58 in America: J. Edwin Orr on the History of Revival – YouTube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dd9gfdes9Fw