1859 The Aberdeen Revival

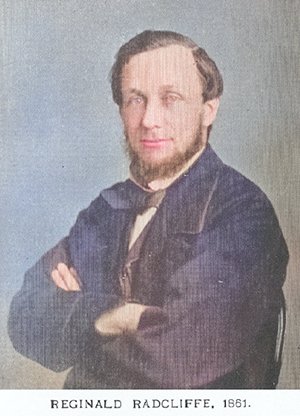

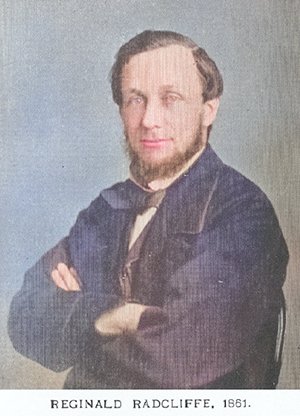

Reginald Radcliffe

Introduction: A National Spark

Reginald Radcliffe

In the annals of Scottish religious history, the great awakening of 1859-61 stands as a monumental event, a period of intense spiritual fervour that reshaped communities and fuelled a generation of social action.1

While its impact was felt across the nation, from the industrial heart of Glasgow to the remote Western Isles, historical analysis identifies the city of Aberdeen as the true crucible of this movement. The Aberdeen Revival, which ignited in the autumn and winter of 1858, was not merely a localized event but the crucial, initiating spark for the wider Scottish Awakening.2

This revival marked a departure from earlier Scottish awakenings, such as the famous Cambuslang Wark of 1742.4 It was a distinctly modern phenomenon, born from a confluence of transatlantic communication, post-Disruption religious zeal, and innovative evangelistic methods.

While some sources point to Glasgow as a key epicenter, the documented prayer meetings and the arrival of pivotal evangelists in Aberdeen in late 1858 predate the major events in other cities, establishing its claim as the movement’s starting point.3

This report analyses the antecedents that prepared the ground for revival, profile its key leaders, provide a narrative of the events in Aberdeen, trace its remarkable spread, and assess its profound and lasting impact.

The Climate of Expectancy: Antecedents to the 1859 Aberdeen Revival

The Aberdeen Revival did not emerge from a vacuum. It was the culmination of international and national developments that created a fertile ground for a spiritual awakening, fostering what contemporaries described as a “spirit of great expectancy”.5

A Transatlantic Awakening

The broader movement, often termed the Third Great Awakening, began not in Scotland, but in North America.6 In September 1857, a lay missionary named Jeremiah Lanphier started a noon-hour prayer meeting in New York City.4 Initially attended by only a handful of people, these meetings exploded in popularity following a financial crash, spreading across the United States in what became known as the “Layman’s Revival”.8

News of this American awakening crossed the Atlantic, disseminated through the burgeoning newspaper industry and personal accounts.3 The reports captivated a Scottish audience. In 1858, the Free Church General Assembly invited an American minister, Revd Dr. Maclean, who enthralled the gathered pastors with his account of what God was doing in his country.4

This was powerfully reinforced by the explosive 1859 revival in Ulster, Northern Ireland. The proximity and intensity of the Ulster revival prompted scores of Scottish ministers and laypeople to travel and witness it firsthand. Of the 123 British clergymen who made the journey, 40% were from Scotland, returning with “glowing reports” and a fervent desire to see a similar movement at home.4

The Post-Disruption Landscape of Scottish Religion

The domestic religious climate was uniquely prepared for such a movement.a The Great Disruption of 1843, a schism that saw 450 evangelical ministers break from the established Church of Scotland to form the Free Church of Scotland, had created a large, dynamic, and deeply committed evangelical body.11

This new denomination, which saw itself as a “champion of revivals,” was theologically and culturally primed for an awakening and would become the heart of the 1859 movement.4

However, in the years leading up to 1858, the spiritual state of many areas, including Aberdeenshire and Banffshire, was described by observers as “the Dead Sea”.13

A formal religion of morality was often preached in place of a personal experience of salvation by grace, creating a spiritual vacuum and a deep hunger for something more vital.13

The Ground Prepared in Aberdeen

This combination of international news and domestic hunger converged in Aberdeen. Reports of the American and Irish revivals published in local newspapers stirred “considerable interest in Aberdeen”.3

This interest was not passive; it translated into action. In September 1858, united prayer meetings were established in the city with the specific aim of asking God to send the revival to Aberdeen and Scotland.3 This proactive, expectant faith prepared the soil for the seed that was about to be sown.

The Human Instruments: Leaders of the Awakening

The revival was catalysed by a dynamic interplay between charismatic itinerant evangelists and key local figures who provided the platforms and legitimacy necessary for the movement to flourish.

Reginald Radcliffe: The Power of Persuasion

Reginald Radcliffe, a lawyer’s son from Liverpool, was a young, energetic lay evangelist.15 Known for his clear voice and methodical approach, which included organized tract distribution at public events, he was invited to Aberdeen by Professor William Martin of Marischal College, arriving on November 27, 1858.15 Initially facing clerical opposition to lay preaching, Radcliffe employed a shrewd strategy, beginning his ministry by holding “addresses” for children in a small mission hall.13

The evident transformation in the children soon attracted their parents, and his reputation grew.15 His preaching was not characterized by soaring eloquence but by a simple, persuasive power, focusing on the comforting message that “God is love”.5 He was also an innovator, pioneering the use of targeted meetings and “inquiry rooms” where those anxious about their spiritual state could receive personal counsel after a service—a method that would be used to great effect by later evangelists like D. L. Moody.3

Brownlow North: From Profligate to Preacher

Arriving in Aberdeen for a mission around the same time as Radcliffe was Brownlow North, a man of starkly different background and temperament.15 A member of the aristocracy, North had lived a notoriously wild and profligate life of gambling and excess before a dramatic conversion in 1854.16

He actively sought Radcliffe’s cooperation, and their partnership proved immensely powerful.15 Where Radcliffe persuaded, North confronted. His preaching was marked by “tremendous earnestness and force,” driving home the “awful and glorious” truth that “God is”.15 His own dramatic testimony of transformation from a great sinner to a zealous preacher was a compelling tool that resonated deeply with his audiences.16

The Local Sanction: Aberdeen’s Indispensable Facilitators

The efforts of these itinerant evangelists would have remained on the fringes without the support of influential local figures. Professor William Martin not only issued the initial invitation to Radcliffe but also provided practical support by counselling anxious souls during the meetings.15 Even more critical was the role of Reverend James Smith, minister of Greyfriars Church.

At a time when most established clergy were suspicious of lay preachers, Rev. Smith was “deeply stirred” by the work and opened the doors of his prominent church, the collegiate church of Marischal College.15

This act of sanction was the turning point, moving the revival from a small mission hall into the heart of Aberdeen’s religious life and providing the large platform that allowed the movement to “deepen and widen” in the closing days of 1858.15

A Narrative of the Revival in Aberdeen

The revival unfolded in distinct phases, escalating from quiet prayer to a city-wide spiritual conflagration over the course of six months.

September-November 1858: The Preparatory Phase. The period began with the formation of the expectant, united prayer meetings.3 Smaller-scale evangelistic campaigns by figures like Brownlow North and Grattan Guinness further “prepared the way,” heightening the sense of anticipation.3

November-December 1858: The Ignition. Radcliffe’s arrival on November 27th was the catalyst. He began with children at the Albion Street Mission Hall before being invited to the Bon Accord Free Church, where he addressed children while adults listened from the gallery.15

The decisive moment came when Rev. James Smith opened Greyfriars Church, giving the movement a central and capacious venue. The work immediately began to expand.15

January-March 1859: The Conflagration. The new year saw an explosion of interest. In a letter dated January 17, 1859, Radcliffe described the scene at Greyfriars, which was “crammed in all directions,” with people being turned away. The demand was so great that they held three consecutive services in a single evening, followed by hours of personal counseling with the “anxious” in the pews because the vestry was too small to hold them all.15

The work grew to three or four meetings daily, continuing with “extraordinary blessing” until Radcliffe’s departure on March 18, 1859.15 The meetings themselves, at least within the formal church settings, were characterized by an intense but orderly atmosphere, with a focus on the “simple Gospel” and a deliberate suppression of overt emotionalism.3

Table 1: Timeline of the Aberdeen Revival and its Wider Context (1843-1861)

| Year/Date | Event in Aberdeen | Event in Scotland | International Context |

| 1843 | The Great Disruption forms the Free Church of Scotland.11 | ||

| 1854 | Brownlow North experiences his conversion.16 | ||

| 1857 (Sept) | Jeremiah Lanphier’s first prayer meeting in New York begins the “Layman’s Revival”.8 | ||

| 1858 (Sept) | United prayer meetings begin in the city to pray for revival.3 | ||

| 1858 (Nov 27) | Reginald Radcliffe arrives in Aberdeen at the invitation of Prof. Martin.15 | ||

| 1858 (Dec) | Revival deepens and widens as meetings are held in Greyfriars Church.15 | ||

| 1859 (Jan 17) | Radcliffe reports Greyfriars is “crammed,” requiring three services in one night.15 | ||

| 1859 (Spring/Summer) | Many Scottish ministers and laypeople visit the Ulster Revival, which is at its height.4 | ||

| 1859 (July 24) | Revival breaks out in Glasgow following preaching by John Horner.4 | ||

| 1859 (Autumn) | Revival spreads from Aberdeenshire to the Moray Firth fishing villages.14 | ||

| 1860 (Aug 19) | A crowd of thousands gathers for an open-air revival meeting on Glasgow Green.4 | ||

| 1861 | The main wave of the revival gradually subsides.2 |

The Spread of the Flame: From the City to the Coast

The fire ignited in Aberdeen did not remain contained. It spread rapidly into the surrounding hinterland, its character adapting to the distinct cultural landscapes it encountered.

The Revival in the Fishing Villages: The Ministry of James Turner

The fishing communities along the Moray Firth were a world apart from urban Aberdeen. Described as a “hardy, daring… and clannish” people, they were largely uneducated and struggled with alcoholism and debt.19 The key instrument for revival in this region was

James Turner, a cooper and lay evangelist from Peterhead.19

Beginning in the winter of 1859, Turner travelled along the coast, and the revival that followed was raw and intensely emotional.

In villages like Portknockie and Findochty, the awakening was marked by dramatic physical and emotional manifestations. People were “struck down” under conviction of sin, crying out for mercy in their homes, on the shore, and even in “the very holes and caves in the rocks”.19

The Banffshire Journal reported that “scarcely a family in the village” was unaffected.19 Unlike the more restrained services in Aberdeen, these meetings were characterized by a powerful, collective catharsis. New converts, instead of waiting for instruction, would immediately go out to evangelize their friends and neighbors, causing the revival to spread with astonishing speed.19

The Awakening in the Country Parishes: Stories from the Hinterland

The revival also penetrated the rural farming parishes. A powerful account comes from Old Meldrum, a town seventeen miles north of Aberdeen, as recorded by a local physician, Dr. R. McKilliam.5 When Radcliffe came to preach in the large Free Church, the crowd was initially disappointed by his simple, unadorned style.

After his address, he invited the “anxious” to remain, but most of the congregation left. Facing a handful of discouraged workers, Radcliffe simply prayed, “Friends, have faith in God. Let us ask God to send them back”.5 As he prayed, people began to trickle back in, then in crowds, until the church was one-third full again.

What followed was a “wondrous breakdown,” with “boys, girls, young men and women, old, grey-haired fathers and mothers, [weeping] together like babies”.5 The event transformed the town’s social life; for a long time afterward, social evenings were set aside for prayer meetings and Bible studies.5

A Transformed Region: The Impact and Results of the Revival

The revival’s effects were profound and measurable, transforming individual lives, churches, and the wider society.

A Harvest of Souls: Assessing Converts and Church Growth

The number of converts was staggering. While precise figures are unverifiable, revival scholar J. Edwin Orr estimated that the 1859-61 awakening resulted in approximately 300,000 converts across Scotland, about 10% of the population.1 More conservative estimates agree that the number ran into the “numerous tens of thousands”.1

The impact on churches was dramatic. The Free Church alone recorded over 15,000 new members in 1859, and church attendance across denominations soared, with some congregations doubling or even quadrupling in size.1

The United Presbyterian Church saw its prayer meetings double and its regular Sunday attendance increase by over 50%, a level that was sustained for many years after.1 The converts were drawn from all classes but were predominantly young and from the lower echelons of society: craftsmen, servants, tenants, and a high proportion of unmarried women.9

A Revolution in Morals: The Social and Cultural Impact

The spiritual awakening produced a tangible revolution in public morality. In Edinburgh, recorded instances of alcoholic addiction fell by 55% between 1859 and 1864.1 Crime rates dropped noticeably wherever the revival took hold. In Dumfriesshire, the rural police reported that their office had become “all but a sinecure”.2

In the fishing villages of the north-east, the transformation was so complete that public houses were forced to close and were replaced by houses of prayer.19 Contemporary observer George Gardiner wrote of the region, “The whole face of society in those villages is so changed that those who have known them before are struck with wonder”.1

The Enduring Legacy: Fuelling a Generation of Service

Perhaps the most significant legacy of the revival was its long-term impact. The retention rate among converts was remarkably high; in villages like Ferryden, nearly all who professed faith were still active Christians three decades later.1 More importantly, the revival created a vast cohort of motivated laypeople who became the engine for the great social and missionary movements of the late Victorian era.

As historian T.T. Matthews concluded, “All the mission movements — home and foreign — philanthropic schemes, and measures for the alleviation of human suffering, have been mainly manned and maintained during the last fifty years by the converts of the Revival of ‘59 and the sixties”.1

Conclusion: Distilling the Lessons of the 1858 Revival

The 1858 Aberdeen Revival and the subsequent Scottish Awakening offer enduring lessons on the dynamics of spiritual and social movements. A synthesis of the historical data reveals several beneficial take-aways:

- The Power of Prayerful Expectancy. The revival was not an accident. It was preceded by a deliberate, sustained period of focused prayer, fueled by news from abroad. This created a spiritual and psychological readiness among the people that was a critical precondition for the outbreak.3

- The Synergy of Lay and Clerical Ministry. The movement demonstrates the potent combination of the “freshness and force” of lay evangelists with the legitimacy and pastoral oversight provided by supportive local clergy. Neither Radcliffe and North nor Rev. Smith could have achieved such an impact in Aberdeen alone; their collaboration was essential.3

- The Importance of a Simple, Christ-Centred Gospel. The evangelists’ messages were noted for their directness, focusing on core truths like the reality of God (“God is”), His character (“God is love”), and the free offer of salvation (“salvation as a gift”).15 This clarity cut through the prevailing formal religion of the day.13

- The Strategic Use of Modern Methods. The revival’s leaders were not averse to innovation. They effectively harnessed the tools of their time—newspapers for communication, railways for rapid travel, and new techniques like the inquiry room—to amplify their message and spread the movement with unprecedented speed.3

- The Primacy of Local Context. The revival was not a monolithic event. Its expression was culturally translated, varying dramatically between the orderly city, the emotional coast, and the devout countryside. This shows that genuine spiritual movements interact with and are shaped by the communities they enter.5

- The Transformative Potential of Individual Conversion for Societal Good. The ultimate significance of the 1858 revival lies in its documented, large-scale impact on public morality and its role in mobilizing a generation of believers. The personal transformations it wrought translated directly into decades of positive social action, foreign missionary work, and philanthropic enterprise, leaving a lasting mark on Scottish society.1

Works cited

- Scottish Revival Series: Lasting Fruit – Christian Heritage Edinburgh, accessed on July 25, 2025, https://www.christianheritageedinburgh.org.uk/2024/03/28/scottish-revival-series-lasting-fruit/

- Remembering the 1859 Revival in Scotland – Christian Study Library, accessed on July 25, 2025, https://www.christianstudylibrary.org/article/remembering-1859-revival-scotland-0

- Revival in Scotland 1859-61 – UK Wells, accessed on July 25, 2025, https://ukwells.org/revivalists/revival-in-scotland-1859-61

- Scottish Revival Series: 1859-61 (Part 1) – Christian Heritage …, accessed on July 25, 2025, https://www.christianheritageedinburgh.org.uk/2024/03/28/scottish-revival-series-1859-61-part-1/

- Oldmeldrum – Reginald Radcliffe (1859) – UK Wells, accessed on July 25, 2025, https://ukwells.org/wells/oldmeldrum-reginald-radcliffe

- The Third Great Awakening – Entry | Timelines | US Religion, accessed on July 25, 2025, https://www.thearda.com/us-religion/history/timelines/entry?etype=3&eid=51

- Third Great Awakening – Wikipedia, accessed on July 25, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Third_Great_Awakening

- ERT (2007) 31:1, 30-42 – Prayer Revivals and the Third Great Awakening – Restoring The Core, accessed on July 25, 2025, https://www.restoringthecore.com/wp-content/restored/Prayer%20Revivals%20and%20The%20Third%20Great%20Awakening.pdf

- Evangelical revival in Scotland – Wikipedia, accessed on July 25, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Evangelical_revival_in_Scotland

- Revival and the Clash of Cultures: Ferryden, Forfarshire, in 1859, accessed on July 25, 2025, https://www.stir.ac.uk/research/hub/file/730630

- Disruption of 1843 – Wikipedia, accessed on July 25, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Disruption_of_1843

- A Church for Scotland? The Free Church and Scottish Nationalism after the Disruption, accessed on July 25, 2025, https://www.euppublishing.com/doi/abs/10.3366/sch.2020.0019

- Reginald Radcliffe – UK Wells, accessed on July 25, 2025, https://ukwells.org/revivalists/reginald-radcliffe

- Revivals Rediscovered N E Scotland » Young Resources, accessed on July 25, 2025, https://www.youngresources.co.uk/revivals-in-n-e-scotland/revivals-rediscovered-n-e-scotland/

- “A Goodly Heritage” (39): Revival in North East Scotland (Part 1 …, accessed on July 25, 2025, http://www.believersmagazine.com/bm.php?i=20160403

- Brownlow North – UK Wells, accessed on July 25, 2025, https://ukwells.org/revivalists/brownlow-north

- Brownlow North – From a Life of Sin to a Life of Service – Edinburgh Free Church (Continuing), accessed on July 25, 2025, http://www.elec8070.plus.com/articles/andy_brownlownorth.htm

- Brownlow North: A Zealous Preacher – Banner of Truth UK, accessed on July 25, 2025, https://banneroftruth.org/uk/resources/articles/2003/brownlow-north-a-zealous-preacher/

- The Moray Revivals – UK Wells, accessed on July 25, 2025, https://ukwells.org/revivalists/the-moray-revivals

- The Revival of 1859 in Scotland – Christian Study Library, accessed on July 25, 2025, https://www.christianstudylibrary.org/article/revival-1859-scotland

- The 1858-62 revival in the North East of Scotland – STORRE, accessed on July 25, 2025, https://dspace.stir.ac.uk/handle/1893/1862