Revivalist Preaching

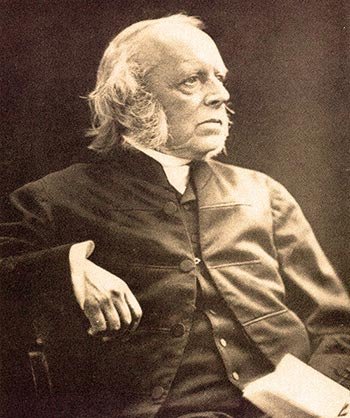

Horatius Bonar

Andrew Bonar

There is a breadth and power about their preaching— a glow and energy about their words and thoughts, that makes us feel that they were “men of might.” Their trumpet gave no feeble nor uncertain sound, either to saint or sinner— either to the church or the world. They lifted up their voices, and spared not. There was no flinching, no flattering, or prophesying of smooth things.

Perhaps they excelled more in the proclamation of the law, and its eternal penalties, than in the declaration of the glad tidings of great joy, through Him who finished transgression, and made an end of sin upon the cross. There is sometimes a lack of fulness and liberty in their statements of the gospel; there is a constraint about some of their sermons, as if they feared making the glad tidings too free; there is, in their dealings with inquirers, a tendency to throw them in upon their own acts, or feelings, or convictions, instead of drawing them out at once to what has been finished on the cross, leading them to look for some preparatory work in themselves, before rejoicing in the gospel; but still there are at other times full exhibitions of the Saviour, and free proclamations of his glorious gospel.

Their preaching seems to have been of the most masculine and fearless kind, falling on the audience with tremendous power. It was not vehement, it was not fierce, it was not noisy; it was far too solemn to be such; it was massive, weighty, cutting, piercing, sharper than a two-edged sword. The weapons wielded by them were well tempered, well furbished, sharp and keen. Nor were they wielded by a feeble or unpractised arm. These warriors did not fight with the scabbard instead of the blade. Nor did they smite with the flat instead of the edge of the sword. Nor did they spare any effort, either of strength or skill, which might carry home the thrust or the stroke to the very vitals. Hence so many fell wounded under them, such as in the case of the celebrated Thomas Shepard of Cambridge, regarding whom it is said, that “he scarce ever preached a sermon but some or other of his congregation were struck with great distress, and cried out in agony, What shall I do to be saved.”

Or take the following account of the effects produced by a sermon of Edwards at Enfield, in July 1741, which, as being new, we lay before our readers: —

“While the people in the neighbouring towns were in great distress for their souls,” says the historian, “the inhabitants of that town were very secure, loose and vain. A lecture had been appointed at Enfield; and the neighbouring people, the night before, were so affected at the thoughtlessness of the inhabitants, and in such fears that God would, in his righteous judgment, pass them by, while the divine showers were falling all around them, as to be prostrate before him a considerable part of it, supplicating mercy for their souls.

When the appointed time for the lecture came, a number of the neighbouring ministers attended, and some from a distance. When they went into the meetinghouse, the appearance of the assembly was thoughtless and vain. The people hardly conducted themselves with common decency. Edwards preached.

His plain, unpretending manner, both in language and delivery, and his established reputation for holiness and knowledge of the truth, forbade the suspicion that any trick of oratory would be used to mislead his hearers, He began in the clear, careful, demonstrative style of a teacher, solicitous for the result of his effort, and anxious that every step of his argument should be early and fully understood. His text was Deut. xxxii. 35. ‘Their foot shall slide in due time.’

As he advanced in unfolding the meaning of the text, the most careful logic brought him and his hearers to conclusions, which the most tremendous imagery could but inadequately express. His most terrific descriptions of the doom and danger of the impenitent, only enabled them to apprehend more clearly the truths which he had compelled them to believe.

They seemed to be, not the product of the imagination, but what they really were, a part of the argument. The effect was as might have been expected. Trumbull informs us, that ‘before the assembly was ended, the assembly appeared deeply impressed and bowed with an awful conviction of their sin and danger. There was such a breathing of distress and weeping, that the preacher was obliged to speak to the people and desire silence, that he might be heard. This was the beginning of the same great and prevailing concern in that place, with which the colony in general was visited.’”