Pre-1700 Revivals

John Knox

In studying the broad sweep of revival histories it is not difficult to concur with the eighteenth-century evangelicals’ view that ‘revival is the engine of history,’ the most powerful gift of God for the expansion of His church and for the renovation or reform of human society.

To quote Jonathan Edwards’, the first ‘theologian of revival,’ “Indeed, it is true to say that seasons of revival have always been the major means that God has employed to advance His cause and the cause of the church in the world.

Though there be a more constant influence of God’s Spirit always, in some degree, attending His ordinances, yet the way in which the greatest things have been done towards carrying on this work, always has been by remarkable effusions of the Spirit at special seasons of mercy…”

Students of revival today agree with these views but their conclusions are similarly based on historical records from the post-reformation period through to modern times. But what about the period between the first and the seventeenth century? Revival records before the Reformation appear scant and rare, not having the same impact and extensive influence as their later counterparts.

This scarcity of material may easily be explained. During the first four centuries the church was very often under siege from Roman persecutors and much Christian literature was hidden, lost or destroyed. After this the church entered what has become known as the Dark Ages for a thousand years, until the dawning of the light which led to the Reformation.

There had been a widening rift between the Spirit-filled religion of Jesus and an alternative Christianity which married various philosophies and pagan ideas to a ritualistic and clergy-dominated organisation. The spiritual fire simply went out!

Nevertheless, during this dark period there were ‘seasons of refreshing’ which occasionally fanned the embers of authentic Christianity. Though literature is in short supply there is sufficient data in the writings of the early church Fathers and later materials, suggesting there were significant moves of God in the first five centuries, details of which can be found elsewhere on this site.

There are occasional references to outpourings of the Spirit during the Dark Ages and the literature becomes more common as the light began to dawn in the 16th century.

It’s challenging to provide an exhaustive list of every Christian revival before 1700, as historical records are incomplete, and the term “revival” can be interpreted in different ways. However, here is a list of notable examples, focusing on revival movements of significant impact:

Pre-Reformation Era:

Early Church Revivals (c. 30-300 AD): The Book of Acts describes periods of intense spiritual growth and conversion in the early Christian church, fuelled by the Holy Spirit. From Acts 2, which is often seen as the model of revival, onwards Key figures include Peter, Paul, and other apostles.

The period following the apostles (roughly 100-300 AD) was a time of dynamic expansion and spiritual fervor for the early Church. Here’s how this era can be seen as a period of ongoing revival:

Grassroots Evangelism: While lacking the apostles’ prominence, countless ordinary Christians passionately shared their faith. This “everyday evangelism” fuelled growth, spreading Christianity along trade routes and into new communities.

The Spirit’s Power: The Book of Acts highlights the Holy Spirit’s role in the early Church, and this continued. Accounts from the post-apostolic period and beyond, tell of healings, prophetic utterances, and other manifestations of the Spirit’s work, drawing many people to Christ.

Martyrdom as Witness: Facing Roman persecution, Christians’ courageous faith in the face of death proved compelling. Martyrs like Polycarp and Ignatius became powerful examples, inspiring others and demonstrating the reality of their beliefs and their extraordinary faith and courage. As has been said, “the blood of the martyrs was the seed of the church”.

Intellectual Engagement: Early apologists like Justin Martyr and Tertullian skillfully defended Christianity in the public square, using reason and philosophy to engage both skeptics and the educated elite. This intellectual vibrancy attracted many converts and countered misconceptions about the faith.

Local Revivals: While not always empire-wide, historical records indicate localized revivals within specific regions or cities. The work of figures like Irenaeus in Gaul and Gregory Thaumaturgus in Pontus led to significant conversions and spiritual renewal in their communities.

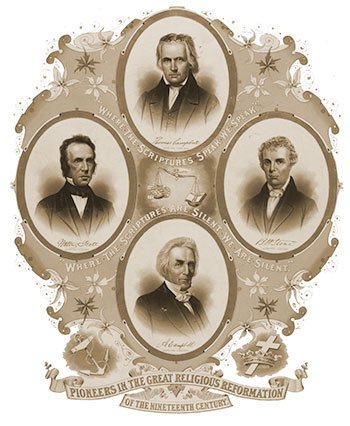

Pre-1700 Revivals – Emphasis on Growth:

Rapid Expansion: Despite persecution, Christianity spread rapidly. By 300 AD, it had reached most corners of the Roman Empire and beyond, establishing churches in most major cities and rural areas alike.

Numerical Strength: While precise figures are debated, estimates suggest that Christians grew from a few thousand at the end of the 1st century to perhaps several million by 300 AD, representing a significant portion of the Roman empire’s population.

Social Diversity: Christianity attracted people from all walks of life – slaves, merchants, intellectuals, and even some within the Roman aristocracy and officialdom. This diverse following contributed to its dynamism and resilience.

This post-apostolic era wasn’t simply a “holding pattern” but a time of active growth and spiritual vitality. The early Church, fuelled by the Spirit and the commitment of its members, continued to experience revival and advance the Gospel despite facing significant challenges. This period laid the groundwork for Christianity’s eventual triumph in the Roman Empire and its enduring impact on the world. It laid the foundation for Christianity as a major world religion.

Monastic Revivals (Various periods): Throughout the Middle Ages, monastic orders like the Benedictines, Franciscans, and Dominicans experienced periods of renewed spiritual fervour and reform. Though far from being ‘evangelicals,’ key figures like Francis of Assisi and many of the the Dominicans, who were founded to preach the gospel and to oppose heresy, influenced many for Christ, though their teachings were peppered with growing extra-biblical doctrines and ideas.

Medieval Period:

Irish Monastic Revival (6th-8th centuries): The flourishing monasticism in Ireland with figures like Columba and Columbanus, spread Christianity to Scotland and continental Europe.

Significance: Preserved Christian learning during the “Dark Ages” and contributed to the evangelization of Europe.

Cluniac Reforms (10th century): Reform movement within Benedictine monasticism, starting in Cluny, France. Aimed to restore the spiritual integrity and independence of monastic life.

Significance: Addressed corruption and laxity within monasteries, leading to a spiritual renewal in Western Europe. Obviously not evangelical revival, but surely a flame of renewal sent by God to ignite the embers of a waning spirituality.

Cistercian Revival (12th century): Reform movement within Benedictine monasticism, emphasizing a simpler, more austere lifestyle and a return to manual labor. Key figure: Bernard of Clairvaux.

Significance: Similar to the Cluniac renewal there were further reforms in monastic life which kept the spiritual flames burning, if only faintly.

Important Considerations:

These smaller revivals often had a significant impact on local communities and laid the groundwork for later, larger movements.

They highlight the ongoing dynamic of spiritual renewal and reform within Christianity.

Studying these smaller revivals can provide a more nuanced understanding of the history of Christianity.

Reformation and Post-Reformation Era:

Waldensian Revival (1170s): A pre-Protestant revival movement in France led by Peter Waldo, emphasizing poverty, preaching, and lay involvement. Faced persecution but influenced later reformers.

Significance: They provided an early challenge to the authority of the Catholic Church, foreshadowing the Reformation.

Lollard Movement (late 1300s – early 1500s): Led by John Wycliffe in England, emphasizing Bible translation and preaching in the vernacular. Faced persecution but influenced later reformers.

Significance: Contributed to the development of English religious thought and paved the way for the English Reformation.

Hussite Movement (early 1400s): Led by Jan Hus in Bohemia, emphasizing reform within the Catholic Church and challenging papal authority. Led to a series of wars and influenced the Reformation.

Significance: Challenged the authority of the Catholic Church and inspired later reformers.

The Reformation (1517 – 16th Century): Though not a single event, the Reformation was a period of widespread religious upheaval and renewal. Key figures include Martin Luther, John Calvin, and Ulrich Zwingli.

Significance: Reshaped European Christianity, leading to the establishment of Protestant denominations and impacting political and social structures. Though the Reformation cannot be described as text-book revival, its effect built a strong basis of Bible based-preaching, especially emphasising justification by faith and producing the widespread growth of Christianity.

Scottish Reformation (mid-1500s): Led by John Knox, this vibrant movement established Presbyterianism in Scotland, planting Reformation doctrines in the heart of Scottish Christianity.

Significance: Profoundly shaped Scottish society and religious life, which produced subsequent and periodic revivals across Scotland.

Hessen Revival (1526-1531): Inspired by the Reformation, this revival in Hesse, Germany, led to widespread religious and social reforms.

Significance: Demonstrated the impact of the Reformation on a regional level and led to the establishment of a Protestant church in Hesse.

Geneva Revival (1536-1564): Under John Calvin’s leadership, Geneva became a center of Protestant reform and experienced a period of intense religious zeal.

Significance: Established Geneva as a model Protestant city and influenced Reformed theology and practice.

Dutch Second Reformation (late 16th – early 17th century): A period of spiritual renewal and further reform within the Dutch Reformed Church. Key figure: Willem Teellinck.

Significance: Deepened the impact of Calvinism in the Netherlands and influenced Dutch culture and society.

Puritan Awakening (late 1500s – 1600s): A movement within the Church of England seeking further reform and emphasizing personal piety and strict moral conduct. Key figures include Richard Baxter and John Bunyan. Revival was always ‘the Puritan Hope’ and became the experience of many.

Significance: Influenced English religious and political life, contributing to the English Civil War and the settlement of North America.

English Nonconformist Revivals (1600s): Various localized revivals among Puritan and other dissenting groups during a time of religious and political turmoil.

Significance: Sustained religious fervor among those who separated from the Church of England and contributed to the development of Nonconformist traditions.

Pietism (late 1600s – early 1700s): A movement within Lutheranism emphasizing personal piety, small group fellowship, and social concern. Key figures include Philipp Spener and August Hermann Francke.

Significance: Pietism played a significant role in laying the foundation for many revivals, particularly those in the 18th and 19th centuries. Here’s how:

Pietism’s Core Emphases:

Personal Piety: Pietism stressed a deeply personal and emotional experience of faith, emphasizing conversion, holiness, and a close relationship with God. This focus on individual transformation primed the ground for revival movements that sought to awaken spiritual fervor in individuals and communities.

Small Groups and Bible Study: Pietists gathered in small groups for prayer, Bible study, and mutual encouragement. This practice fostered spiritual growth and community, creating fertile soil for revival to spread.

Social Concern: Pietism promoted active engagement with the world, including social reform and compassionate service to the poor and marginalized. This social conscience often fueled revival movements that sought to address societal ills and bring about moral and spiritual renewal.

Missionary Zeal: Pietists were passionate about spreading the Gospel, both locally and abroad. This missionary impulse contributed to the growth of revival movements that sought to evangelize the unconverted and expand the reach of Christianity.

Pietism’s Influence on Revivals:

German Pietism: The Pietist movement, which originated in 17th-century Germany, directly influenced later revivals in Germany and other parts of Europe. Its emphasis on personal piety and small group fellowship laid the groundwork for the Great Awakenings in North America and the revivals associated with Methodism in England.

Moravian Pietism: The Moravian Church, a Pietist denomination, played a key role in spreading revivalism through its extensive missionary work. Their emphasis on personal experience and emotional expression influenced figures like John Wesley and contributed to the evangelical revivals of the 18th century.

Methodism: John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, was deeply influenced by Moravian Pietism. He adopted their practices of small groups, accountability, and personal testimony, which became hallmarks of Methodist revivals.

Key Takeaways:

Pietism’s emphasis on personal piety, small groups, social concern, and missionary zeal created a fertile ground for revivals to take root and flourish. Its influence can be seen in various revival movements across Europe and North America, shaping their character and contributing to their impact.

While Pietism wasn’t the sole cause of revivals, it provided a crucial foundation by fostering a culture of spiritual renewal, personal transformation, and active engagement with the world.

Notes:

This list is not exhaustive. Many other smaller revivals and awakenings occurred during this period. Some of these movements were met with resistance and persecution from religious and political authorities. These revivals often had lasting impacts on theology, church structures, and social reform.

For further research

For a more comprehensive history of this period go here.

External links

Early Church Revivals