1840s Revival in Canada

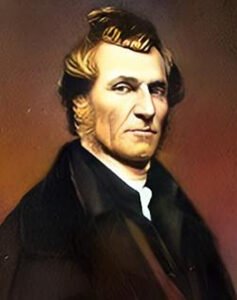

James Caughey

Introduction: The Spiritual Climate of a Young Nation

Christian revivalism describes a time of divine visitation, a restoration of the Church to a state of vitality and fervent faith, especially after perceived seasons of spiritual coldness. Historically, these revivals are marked by an torrent of intense religious enthusiasm, a surge in personal conversions, emotionally resonant preaching, and a foundational emphasis on a personal, transformative encounter with God.

The historical landscape of Protestantism in North America is defined by successive waves of such movements, the Great Awakenings, which suggest a cyclical rhythm of spiritual decline and renewal.

When we consider “the 1840s Canadian Revival,” we are referring to a sustained era of revivalistic activity that swept across the colonies of British North America. This period was deeply shaped by the Second Great Awakening, the monumental wave of Protestant fervour that began in the United States in the 1790s and whose powerful currents continued to flow well into the 1840s.

While the peak intensity of the Second Great Awakening may have passed in the United States by this time, its theological ideas, evangelistic methods, and spiritual energy continued to animate the religious landscape in Canada. Moreover, impactful revival ministries, most notably that of the dynamic American Methodist evangelist James Caughey, were remarkably active in major Canadian urban centres like Montreal and Quebec City in the years immediately preceding 1847.

His well-documented campaigns offer a vivid snapshot of the religious climate of the time. This exploration will examine the sustained wave of evangelical revivalism that characterized Canada around the mid-1840s. We will explore the antecedents that prepared the ground for this event, the characteristics and key figures of the revivals, the phenomena reported by participants, and the lasting impact of this spiritual awakening on Canadian religion, society, and identity.

Seeds of Fervour: Antecedents to the 1840s Revival in Canada

The revivalistic activities observed across British North America around 1840s did not emerge from a vacuum. They were rooted in earlier waves of religious enthusiasm and shaped by the specific religious and social conditions prevailing in the colonies.

The Maritime Great Awakening: A Canadian Genesis

The first major antecedent was the First Great Awakening, the series of revivals in the British American colonies during the 1740s. It championed the necessity of a personal, emotional conversion experience—the “new birth”—and in doing so, challenged the formalism of many established churches.

This movement found a distinct and powerful echo in the Maritime region of Canada. Beginning around 1775, the impassioned preaching of Henry Alline, a Nova Scotian artisan influenced by New England’s revivalist tradition, ignited what is often termed the Canadian Great Awakening.

Alline’s movement was no simple import; it resonated powerfully within local conditions. Settlers in scattered wilderness communities faced economic precariousness and, with the American Revolution, a deep crisis of identity. Alline’s “New Light” message, emphasizing personal salvation and God’s direct love, offered spiritual solace and a new framework for meaning.

His movement, aided by his hymns, spread throughout Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island, laying a deep and enduring foundation for evangelical denominations, particularly the Baptists and Methodists, who would come to define the region’s religious culture. This early experience highlights a recurring pattern in Canadian religious history: the adaptation of broader revival movements to address specific regional needs.

The Second Great Awakening Reaches North

Following this first wave, the Second Great Awakening emerged in the United States around 1790, continuing with intensity into the 1840s. This wave of evangelical fervour was theologically distinct, characterized by emotional preaching that emphasized individual free will and the universal possibility of salvation—a democratizing departure from stricter Calvinist doctrines. Its primary evangelistic tools were the revival meeting and especially the large, multi-day outdoor camp meeting, which were both intense religious encounters and vital social gatherings on the frontier.

The Second Great Awakening quickly spread into Canada. It proved particularly advantageous for Methodists and Baptists. The Methodists, with their efficient organization of itinerant ministers known as circuit riders, were perfectly structured to reach far-flung settlements.

These tireless preachers on horseback served as spiritual guides and community connectors. The Baptists, with their decentralized structure and practice of ordaining preachers from their own communities, also experienced explosive growth. The pervasive influence of this movement provided the dominant theological framework and methodological approaches for evangelical Protestantism in English Canada, directly shaping the religious environment of the 1840s.

A particularly intense phase occurred in a region of upstate New York known as the “Burned-Over District” due to the frequency of revival “fires” that swept through it. Figures like the revivalist Charles Grandison Finney pioneered “new measures,” including the “anxious seat”—a designated bench where those wrestling with conviction could receive focused prayer.

The porous nature of the border meant that the district’s intense religious atmosphere, its preachers, and its publications inevitably influenced adjacent Canadian regions, making them exceptionally receptive to revivalism.

The Canadian Religious Landscape

The religious landscape of British North America was a mosaic of competing traditions. Established churches held significant institutional power: the Roman Catholic Church was the cultural and spiritual cornerstone of Lower Canada (Quebec), while the Church of England (Anglican) held a privileged position in Upper Canada and parts of the Maritimes, closely intertwined with the colonial administration.

In dynamic contrast, evangelical and non-conformist denominations like the Methodists and Baptists were experiencing rapid growth. This created a palpable tension. The established churches represented tradition, hierarchy, and social privilege. The growing evangelical groups embodied a more democratic, experiential, and revival-oriented Christianity that appealed h2ly to common settlers and those outside the circles of power. This competition created fertile ground for revival movements that challenged the status quo.

Igniting the Flames: Revival Activity in the 1840s

The mid-1840s in Canada represented a powerful continuation of the revivalistic trends established in the preceding decades. The energy of the Second Great Awakening continued to fuel religious activity, with a laser-sharp focus on personal conversion, heartfelt piety, and the urgent mission of winning souls. Several key methods facilitated the spread of this revivalism:

-

Itinerancy:

The traveling preacher was the indispensable agent of the revival. Methodist circuit riders systematically covered vast territories, and Baptist evangelists also travelled extensively. This mobility allowed the revival message to penetrate far beyond established towns into the raw frontier.

-

Protracted Meetings:

Revival efforts almost always involved “protracted meetings,” held nightly over several days or weeks in a single location. This sustained approach allowed for spiritual intensity to build and provided ample opportunity for individuals to respond to the call for conversion.

-

Camp Meetings:

Especially prevalent in newly settled regions, camp meetings were large, multi-day outdoor religious festivals that combined fervent religious services with vital social fellowship. They were often characterized by unrestrained emotional expression, including spontaneous singing, shouting for joy, and praying aloud.

Case Study: The Powerful Ministry of James Caughey

The ministry of James Caughey, an eloquent Irish-born American Methodist preacher, provides a vivid, well-documented illustration of the intense, focused revivalism occurring in major Canadian centres immediately prior to the mid-1840s. Though his major Canadian campaigns had concluded by 1841, his work offers a compelling example of the revival spirit and methods of the era.

Caughey conducted several significant campaigns in Canada. In Montreal, he held a 21-day revival in 1835 where an estimated 400 people professed conversion. He returned for another powerful revival in 1837, and a final visit in 1841 resulted in 200 more conversions and had a notable side effect of galvanizing the local temperance movement.

In St. John’s, Quebec, in 1840, after facing initial discouragement, Caughey persevered, secured a vacant tannery for his meetings, and after three weeks of relentless preaching, saw a revival ignite that led to the formation of a new congregation. In Quebec City, he ministered in late 1840 and early 1841, resulting in approximately 150 conversions.

Caughey’s methods were a model of the era’s revivalist technique. They included nightly services, direct and solemn preaching that emphasized the absolute necessity of the Holy Spirit’s power, and public invitations for seekers to come forward to the communion rail for focused prayer. He stressed the importance of the preacher’s personal holiness.

Caughey’s experiences unequivocally demonstrate that large-scale, focused urban revival campaigns, utilizing specific techniques and generating substantial responses, were a prominent feature of the Canadian religious landscape in the years directly preceding 1847. His success undoubtedly reinforced revivalistic expectations within Canadian Methodism for years to come.

Voices and Manifestations of the Revival

The revivals of the mid-19th century in Canada, influenced by the Second Great Awakening, possessed distinct characteristics in their leadership, preaching, worship, and reported phenomena.

Leadership was a composite of charismatic itinerants like Caughey, settled local pastors who promoted revival, and an indispensable network of influential lay figures. The democratic ethos of Methodism and Baptism relied upon lay participation. Lay preachers, class leaders, and “exhorters” played a vital role in extending the church’s reach. Prayer meetings, often initiated and sustained by laypeople, were considered the essential engine of revival.

Furthermore, historical analyses show that women and young people formed the significant majority of converts. This widespread grassroots energy demonstrates that revivalism was not simply imposed from the top down; it required a broad base of lay commitment and passionate participation.

The character of the revival meetings was vibrant and emotionally expressive:

-

Worship and Preaching:

A core hallmark was the emphasis on emotion and felt experience. Services were often charged with intense feeling, marked by fervent prayer, heartfelt singing of simple hymns, and visible emotional responses from the congregation, such as weeping, shouting, and sometimes ecstatic expressions. The preaching was direct and personal, aimed at securing immediate conversions by confronting listeners with their sinfulness and urging an immediate, life-altering decision for Christ.

-

Meeting Dynamics and the “Anxious Seat”:

The practice of inviting individuals feeling convicted of sin to come to a designated area at the front—the “anxious seat” or “mourner’s bench”—became a central feature. Here, amidst the prayers of the faithful, they could receive focused counsel and encouragement. This physical act of moving forward was a powerful public declaration of intent and a critical moment in the conversion narrative.

-

Supernatural Phenomena:

The broader revival context was rife with phenomena that participants understood as supernatural. The camp meetings were known for dramatic physical and emotional manifestations, including participants shouting, dancing, trembling (the “jerks”), or falling “under the power” of the Spirit. It is highly probable that similar phenomena occurred in intense revival meetings in Canada. More concretely, accounts of James Caughey’s ministry describe moments perceived as extraordinary interventions of the Holy Spirit.

In Montreal, he reported that an “unexpected influence came down upon the people,” moving the entire congregation to tears simultaneously. These events, characterized by a palpable sense of divine presence affecting large groups, were interpreted by participants as supernatural occurrences central to the revival’s impact.

Ripples and Waves: The Lasting Impact

The waves of revivalistic fervour that washed over Canada in the mid-19th century left a deep and lasting imprint on the nation’s religious, social, and cultural landscape, shaping its development in ways that are still discernible today.

Impact on Church Growth and Religious Practice

One of the most significant outcomes was the dramatic growth of evangelical denominations. Methodists and Baptists, with their accessible preaching and effective outreach, became the dominant Protestant forces in many parts of English Canada, permanently shifting the denominational balance of power.

This revivalism also profoundly altered religious practice. The emphasis shifted decisively towards a personal, experiential relationship with God, epitomized by the “born again” conversion experience. Faith became less a matter of inherited tradition and more about an individual’s conscious conviction and moral transformation. Consequently, evangelism—the active winning of souls—became central to the perceived mission of the church.

Social and Cultural Consequences

The impact of mid-century revivalism extended far beyond the church into the broader social and cultural fabric of Canada.

-

Links to Social Reform:

Nineteenth-century evangelicals were frequently and passionately involved in a wide array of social reform movements, driven by a post-conversion desire to combat sin not only in individuals but also in the structures of society. The temperance movement, which sought to combat the pervasive social ill of alcoholism, was a primary cause, h2ly promoted in revivals. Other common concerns included strict Sabbath observance and anti-slavery activism.

-

Foundations for the Social Gospel:

While the primary focus of mid-19th century revivalism was intensely individualistic, its very emphasis on moral responsibility and the possibility of radical transformation laid crucial groundwork for the later Social Gospel movement. This influential movement, which gained prominence in Canada from the 1890s, sought to apply Christian principles directly to systemic social problems arising from industrialization and urbanization, such as poverty and urban squalor.

The earlier revivalistic impulse created an activist mindset and an optimistic belief in societal improvement through concerted Christian action. The Social Gospel was, in many ways, the collective social conscience that grew from the seeds of individual conscience planted by the revivals.

-

Education:

The religious fervour of the era also spurred significant educational initiatives. The growing denominations sought to train their own ministers and educate their adherents, leading to the founding of numerous colleges and seminaries that challenged the Anglican monopoly on higher education, such as the Baptists’ Acadia College and the Methodists’ Victoria College.

-

Shaping Canadian Identity:

Evangelicalism emerged as a powerful, arguably dominant, force within Anglophone Canadian culture during the 19th century. It deeply influenced the cultural ethos of regions like the Maritimes and Ontario, contributing to the pervasive idea of Canada as a “Christian Dominion,” a nation founded on and destined to be guided by Christian principles.

Evangelical morality shaped public life, leading to the rise of “Toronto the Good” and the passing of strict Lord’s Day Acts. These churches and their affiliated organizations were instrumental in establishing a wide range of social institutions, significantly shaping the social infrastructure and moral character of Canadian society as it moved toward Confederation.

Conclusion: A Distinctly Canadian Awakening

The period surrounding 1840s in Canada was not marked by a single, discrete event but represented a vital phase within a sustained era of evangelical activity. Animated by the still-potent energies of the Second Great Awakening, this period witnessed the consolidation of evangelical denominations, who utilized dynamic revivalistic methods to expand their reach across the colonies of British North America.

This era of fervour, characterized by its focus on personal conversion, experiential piety, and the active participation of lay members, profoundly reshaped the nation’s spiritual and social landscape.

The legacy of this mid-century revivalism was profound. It permanently altered the religious demographics and power dynamics within Canadian Protestantism. It transformed religious practice for many, shifting the focus towards personal experience and active evangelism. Crucially, this wave of revivalism contributed to the burgeoning social consciousness of the era, linking evangelical piety with movements for moral and social reform.

This impulse towards societal transformation, rooted in the doctrine of individual moral responsibility, laid essential groundwork for the later rise of the influential Social Gospel movement in Canada.

The study of revivalism in mid-19th century Canada reveals a complex interplay between broad transatlantic religious currents and specific local adaptations. Influences from both the United States and Great Britain were profoundly felt, yet they were always received and implemented within the unique contexts of British North America.

The result was a distinctly Canadian expression of evangelicalism, one that contributed fundamentally to the nation’s religious and cultural development. Understanding this era of fervent religious activity is crucial for comprehending the historical trajectory of religion, social reform, and the enduring influence of faith on the public life of Canada.

Further research