1837 Revival in Hawaii

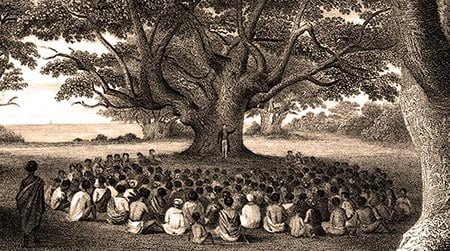

Hawaiian locals hearing the Word of God

The 1837 revival in Hawaii, often called the “Great Awakening,” was a period of intense religious fervour and mass conversions to Christianity. This spiritual awakening had a profound and lasting impact on Hawaiian society and culture, shaping the islands’ religious landscape and leaving an enduring legacy. This article delves into the history of this revival, exploring its antecedents, key figures, notable events, and lasting impact.

Christianity in Hawaii Before 1835

Before Christian missionaries arrived, Native Hawaiians practiced a polytheistic religion deeply intertwined with their daily lives. Their beliefs centred around four primary gods: Lono (agriculture), Kāne (forests), Kanaloa (sea), and Kū (war). A system of kapu (taboos) governed their social and political order1.

However, contact with Westerners introduced new diseases and disrupted traditional ways, leading to social ills such as infanticide2.

The arrival of Protestant missionaries in 1820 marked a turning point. These missionaries, primarily from New England, were sent by the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) with the aim of converting and “civilizing” the Hawaiian people3. However, it’s important to note that Tahitian Christians had already begun missionary work in Hawaii before the arrival of the American missionaries, laying some of the groundwork for the later revival4.

The missionaries established churches and schools, introduced the printing press, and translated the Bible into the Hawaiian language5. Their efforts were aided by the dismantling of the traditional kapu system in 1819 by King Kamehameha II, which created a spiritual vacuum that Christianity readily filled1. By 1835, Protestantism had become the official religion of Hawaii, and a significant portion of the population had embraced the new faith5.

Arrival of the Missionaries and Titus Coan

The first company of missionaries arrived in Hawaii in 1820 aboard the Thaddeus6. Among them were influential figures like Reverend Hiram Bingham, who played a crucial role in developing a written form of the Hawaiian language and establishing the Kawaiaha’o Church in Honolulu7. The missionaries’ arrival was prompted in part by the story of Henry Ōpukaha’ia, a young Hawaiian who travelled to New England, converted to Christianity, and inspired missionary efforts in his homeland8.

Titus Coan, a pivotal figure in the 1837 revival, landed on the shore belt of Hawaii in 18354. Born in Connecticut in 1801, Coan had been deeply influenced by the revivals sweeping through New England during the Second Great Awakening2. He had worked alongside prominent revivalists like Charles Finney and Asahel Nettleton, whose methods and strategies he would later employ in Hawaii2.

The Spark of Revival

While earlier missionary work prepared the ground, several factors ignited the religious fervour of 1837. Widespread and fervent prayer among both missionaries and Hawaiian Christians played a significant role2. The missionaries held prayer meetings and requested prayers from supporters in the United States9. Hawaiian Christians, including the blind preacher Puaaiki, known as the “Blind Preacher of Maui,” devoted themselves to prayer, often gathering in sugarcane and banana groves to intercede for revival2.

A tidal wave that struck the Hawaiian coast in November 1837 also contributed to the revival2. The unexpected disaster and the resulting devastation served as a stark reminder of mortality, prompting many Hawaiians to seek spiritual solace and embrace Christianity2. The tidal wave intensified the revival, not only in Hilo but also on other islands where it left its mark2. This event, combined with the prevailing atmosphere of prayer and anticipation, created fertile ground for the revival to take root and spread.

“On Coan’s first tour multitudes flocked to hear him they thronged him so that he had scarcely time to eat. Once he preached three times before he had a chance to take breakfast. He felt that God was strangely at work.

In 1837 the slumbering fires broke out. Nearly the whole population became an audience. He was ministering to 15,000 people. Unable to reach them, they came to him, and settled down to a two years’ camp meeting. There was not an hour day or night when an audience of from 2,000 to 6,000 would not rally to the signal of the bell.”

(The Revival We Need, by Oswald J. Smith.’ Chapter 2, ‘The Outpouring of the Spirit’)

The Revival Meetings

The revival meetings were characterized by a fervent atmosphere and passionate preaching. Titus Coan, known for his powerful sermons and compassionate nature, drew large crowds9. He preached in churches, homes, and open fields, adapting his message to diverse audiences2. The meetings were often emotionally charged, with attendees experiencing intense conviction of sin and expressing their repentance through weeping, trembling, and even falling unconscious10.

Leaders of the Revival

Titus Coan emerged as a central figure in the 1837 revival2. His passionate preaching, combined with his compassionate nature and dedication to the Hawaiian people, drew large crowds to his meetings9. Coan’s approach was characterized by simplicity, directness, and a focus on the love of God in Christ10. He emphasized personal conversion and encouraged his converts to live out their faith in practical ways. The Holy Spirit played a crucial role in drawing people to Christ during these meetings4.

Other notable leaders included Lorenzo Lyons, a missionary stationed in Waimea, who also witnessed a significant number of conversions during this period9. David B. Lyman, who served alongside Coan for nearly 50 years, played a crucial role in supporting and sustaining the revival2. The collective efforts of these missionaries, along with the fervent prayers and active participation of Hawaiian Christians, fuelled the revival’s momentum. However, it’s worth noting that Coan and Lyons faced criticism from some fellow missionaries who disapproved of the emotional outbursts and fervent displays in their revival meetings9.

Titus Coan’s Travels During the Revival

Titus Coan’s ministry extended far beyond his station in Hilo. He embarked on extensive preaching tours, traveling on foot to reach remote villages and share the Gospel with as many people as possible2. These journeys were often arduous, involving long distances, rugged terrain, and challenging conditions2. Coan’s dedication and commitment to reaching the Hawaiian people are evident in his accounts of these travels.

During one of his tours in the Puna area, Coan encountered a series of flooded rivers that threatened to impede his progress11. With the help of his native companions, he navigated the treacherous waters, determined to fulfil his preaching engagements. In another instance, he crossed a raging river by being carried on the shoulders of strong Hawaiian men who formed a human chain across the torrent11. These accounts illustrate Coan’s unwavering resolve to bring the Gospel to every corner of his parish.

While the research material doesn’t provide a complete list of every town Coan visited during his revival tours, it does mention Puna as one of the areas he ministered in2. His ministry encompassed the entire island of Hawaii, covering a coastal area of over 100 miles2. He preached in villages, homes, and open fields, adapting his message to the diverse audiences he encountered2. His tireless efforts and personal engagement with the Hawaiian people contributed significantly to the revival’s widespread impact.

Supernatural Happenings

The 1837 revival was marked by numerous accounts of unusual events and spiritual manifestations. Many attendees at Coan’s meetings experienced intense emotional responses, including weeping, trembling, and some even collapsing to the ground, seemingly overcome by the power of the message and the presence of the Holy Spirit10. Some described feeling as if a “two-edged sword” was cutting them to pieces, while others cried out for mercy or fell into a swoon10. These manifestations were often accompanied by profound conviction of sin and a desire for repentance.

One notable account involved the conversion of the high priest of Pele, the volcano goddess2. This imposing figure, known for his fierce demeanour and violent acts, was deeply affected by Coan’s preaching and confessed his sins with tears2. His sister, the priestess of Pele, also embraced Christianity, marking a significant turning point in the spiritual landscape of the island.

While some missionaries criticized these emotional displays and questioned their authenticity, Coan viewed them as genuine expressions of the Holy Spirit’s work9. He believed that the revival was a manifestation of God’s power and grace, and he defended the emotional responses as evidence of true repentance and conversion.

“There was trembling, weeping, sobbing, and loud crying for mercy, sometimes too loud for the preacher to be heard; and in hundreds of cases his hearers fell in a swoon. Some would cry out, “The two-edged sword is cutting me to pieces.” The wicked scoffer who came to make sport dropped like a dog, and cried, “God has struck me!” Once while preaching in the open field to 2,000 people, a man cried out, “What must I do to be saved?” and prayed the publican’s prayer, and the entire congregation took up the cry for mercy. For half an hour Mr. Coan could get no chance to speak, but had to stand still and see God work.

Quarrels were made up, drunkards reclaimed, adulterers converted, and murderers revealed and pardoned. Thieves returned stolen property. And sins of a lifetime were renounced. In one year 5,244 joined the Church. There were 1,705 baptised on one Sunday. And 2,400 sat down at the Lord’s Table, once sinners of the blackest type, and now saints of God. And when Mr. Coan left he had himself received and baptized 11,960 persons.” (The Revival We Need, by Oswald J. Smith. Chapter 2, ‘The Outpouring of the Spirit,’)

Lasting Impact of the Revival

The 1837 revival had a transformative effect on Hawaiian society and culture. The mass conversions led to a significant increase in church membership, with Coan’s congregation in Hilo becoming the largest Protestant church in the world at that time12. By 1853, over 56,000 out of a native population of 71,000 were Protestants13. This rapid growth of Christianity contributed to the establishment of numerous churches and the development of a strong Christian identity in Hawaii.

The revival also had a profound impact on social and moral values. Traditional practices such as infanticide and human sacrifice were abandoned, and Christian principles of love, forgiveness, and compassion were embraced2. The revival fostered a sense of community and unity, as Hawaiians from diverse backgrounds came together to worship and support one another.

Furthermore, the revival and the missionaries’ efforts played a crucial role in the development of written Hawaiian and increased literacy among the Hawaiian people14. The translation of the Bible and other texts into the Hawaiian language, along with the establishment of schools, contributed to a greater understanding and appreciation of the written word.

The legacy of the 1837 revival continues to shape Hawaiian society today. The Christian faith remains a central aspect of Hawaiian culture, and the values and principles instilled during the revival continue to influence social and moral norms. The revival also played a role in the development of education and literacy in Hawaii, as missionaries established schools and promoted the use of the written Hawaiian language14.

The Great Mahele

Shortly after the revival, in 1848, a significant event known as the Great Mahele took place. This land redistribution system, while not directly related to the revival, had a profound impact on Hawaiian society and is important to understand in the context of the period. The Great Mahele aimed to divide land ownership among the king, chiefs, and commoners15. However, it ultimately led to significant land loss for Native Hawaiians and contributed to the erosion of traditional land tenure systems. This event further illustrates the complex social and political changes occurring in Hawaii during this era.

Why Were Hawaiians So Receptive to Christianity?

The remarkable receptivity of Hawaiians to Christianity during this period can be attributed to several factors. The dismantling of the kapu system in 1819 left a spiritual void and a sense of uncertainty. Christianity, with its emphasis on forgiveness, hope, and a loving God, offered a new framework for understanding the world and finding meaning in life. The influence of figures like Henry Ōpukaha’ia, who bridged the gap between Hawaiian and Western cultures, also played a role. Furthermore, the missionaries’ efforts to learn the Hawaiian language, establish schools, and engage with the community fostered trust and facilitated the spread of Christian teachings8.

A Complex Legacy

The 1837 revival left a complex legacy in Hawaii. While it brought about positive changes such as the decline of harmful practices and the promotion of education and literacy, it also contributed to the erosion of traditional culture and the imposition of Western values. The revival played a role in the weakening of the Hawaiian monarchy and the eventual annexation of Hawaii by the United States. It’s crucial to acknowledge both the positive and negative consequences of this historical event and its lasting impact on Hawaiian identity and culture16.

Coan’s Later Years

After 35 years of dedicated service in Hilo, Titus Coan embarked on new missionary endeavors. He advocated for a mission by Hawaiians to the Marquesas Islands and even made two voyages there as a delegate of the Hawaiian Missionary Society13. This demonstrates his continued commitment to spreading Christianity and supporting indigenous missionary efforts.

Timeline of the Revival

| Date | Event | People |

| 1778 | Captain James Cook “discovers” the Hawaiian Islands | Captain James Cook |

| 1810 | Kamehameha I unites the Hawaiian Islands | Kamehameha I |

| 1819 | Abolition of the kapu system | King Kamehameha II, Queen Kaʻahumanu |

| 1820 | Arrival of the first missionaries in Hawaii | Hiram Bingham, Asa Thurston |

| 1835 | Titus Coan arrives in Hilo | Titus Coan, Fidelia Church Coan |

| 1836 | Coan begins extensive preaching tours | |

| 1837 | Tidal wave strikes the Hawaiian coast | |

| 1837-1838 | Peak of the revival with mass conversions | Titus Coan, Lorenzo Lyons, Puaaiki |

| 1839 | Over 5,000 people baptized by Coan | |

| 1840 | Continued growth of the church and spread of Christianity | |

| 1848 | The Great Mahele land redistribution | |

| 1853 | Over 56,000 Hawaiians identify as Protestant | |

| 1870 | Coan leaves Hilo after 35 years of ministry |

Conclusion

The 1837 revival in Hawaii was a pivotal event in the islands’ history. Driven by fervent prayer, a tidal wave that served as a reminder of mortality, and the passionate preaching of missionaries like Titus Coan, the revival led to mass conversions and a profound transformation of Hawaiian society. The legacy of this spiritual awakening continues to resonate in Hawaii today, shaping the islands’ religious landscape and influencing social and cultural values.

The revival serves as a powerful example of religious change and cultural transformation. It highlights the complex interplay between indigenous traditions, Western influence, and the enduring human search for meaning and purpose. While the revival brought about positive changes, it also had unintended consequences that continue to shape Hawaii’s relationship with its past and its future.

Works cited

- Religion’s Role in the Annexation of Hawai’i and Hawaiian Cultural Erasure – ScholarSpace, accessed on February 20, 2025, https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/bitstreams/f9a50fc4-4464-4c90-a348-2c96d5a1cec1/download

- 1836 Hawaiian Revival (2 revivals) – BEAUTIFUL FEET, accessed on February 20, 2025, https://romans1015.com/1836-hawaiian-revival/

- Cultural History of Three Traditional Hawaiian Sites (Chapter 5), accessed on February 20, 2025, https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/kona/history5b.htm

- The Powerful Revival in Hawaii – Group Bible Study, accessed on February 20, 2025, https://www.groupbiblestudy.com/post/the-powerful-revival-in-hawaii-3

- Missionaries | the umiverse – WordPress.com, accessed on February 20, 2025, https://theumiverse.wordpress.com/2013/09/25/missionaries/

- Kailua Kona, Hawaii’s Christian History – Mokuaikaua Church, accessed on February 20, 2025, https://mokuaikaua.com/konahistory-2/

- DISplace: Religious Reform | Five Oaks Museum, accessed on February 20, 2025, https://fiveoaksmuseum.org/displace-religious-reform/

- Bicentennial of the Arrival of ABMC Missionaries and Establishment of Three Historic Churches – Historic Hawaii Foundation, accessed on February 20, 2025, https://historichawaii.org/2020/06/19/bicentennial-of-the-arrival-of-abmc-missionaries-and-establishment-of-three-historic-churches/

- HAWAII’S GREAT AWAKENING: 1835-1840 –TITUS COAN And REVIVAL – GospelTruth.net, accessed on February 20, 2025, https://www.gospeltruth.net/hawaii_revival.htm

- Pierson: The Hawaiian Revival – Prevailing Intercessory Prayer, accessed on February 20, 2025, https://www.path2prayer.com/revival-and-the-holy-spirit/titus-coan-revivalist-missionary-in-hawaii/pierson-the-hawaiian-revival

- Titus Coan, US, Missionary – 365 Christian Men, accessed on February 20, 2025, https://365christianmen.com/podcast/titus-coan-us-missionary/

- Titus Coan: Revivalist Missionary in Hawaii – Prevailing Intercessory Prayer, accessed on February 20, 2025, https://www.path2prayer.com/revival-and-the-holy-spirit/titus-coan-revivalist-missionary-in-hawaii

- Coan, Titus (1801-1882) | History of Missiology – Boston University, accessed on February 20, 2025, https://www.bu.edu/missiology/missionary-biography/c-d/coan-titus-1801-1882/

- Aia ke Ola i ka ‘Ōlelo Hawai’i: Revival of the Hawaiian Language – Kamehameha Schools, accessed on February 20, 2025, https://www.ksbe.edu/assets/research/collection/11_0108_ngosorio.pdf

- Historical Timeline » Independent & Sovereign Nation State of Hawaii, accessed on February 20, 2025, https://www.nationofhawaii.org/timeline/

- Struggle for Hawaiian Cultural Survival – Ballard Brief – BYU, accessed on February 20, 2025, https://ballardbrief.byu.edu/issue-briefs/struggle-for-hawaiian-cultural-survival

For further research:

Adventures in Patagonia – Titus Coan

Titus Coan – Wikipedia