Red and Gasper Rivers Revival, America

1800 June-July James McGready

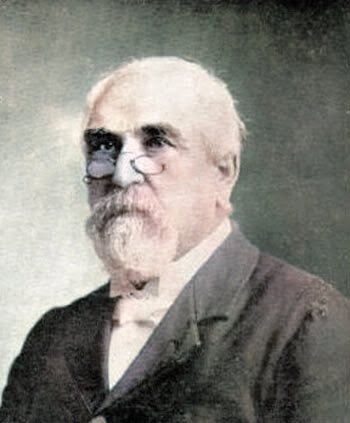

James McGready

A Land Ripe for Revival: The Religious Climate in Kentucky

In the late 18th century, Kentucky was a frontier region with a diverse religious landscape. While Baptists were among the early religious pioneers, establishing churches and promoting public worship, other denominations, including Presbyterians, were also present years before Kentucky achieved statehood. However, the rapid population growth in the 1790s, coupled with the influx of settlers from various backgrounds, created challenges for religious institutions. Church attendance was often sparse, and a sense of spiritual decline permeated many communities.

This decline was not solely anecdotal. Statistical data reveals a concerning trend. In 1790, there were 42 Baptist churches in Kentucky with a membership of 3,105. However, by 1800, despite a significant increase in the overall population, the number of Baptists had not kept pace, with 106 churches and 5,119 members reported 3. This decline in religious engagement alarmed many religious leaders, prompting calls for spiritual renewal. In 1798, the Presbyterian General Assembly designated a day for fasting, humiliation, and prayer, seeking to redeem the frontier from what they perceived as “Egyptian darkness”.

Adding to the complexity of the religious climate, many settlers in Logan County, where the Gasper River revival would take place, were individuals who had fled from established communities in the East, seeking to escape legal troubles or societal constraints 3. This contributed to a culture where violence, gambling, and disregard for religious principles were prevalent. Amidst this environment of spiritual apathy and social unrest, a yearning for religious revival began to emerge. (Tony Cauchi)

James McGready

James McGready, a Presbyterian minister in Kentucky, promoted a “concert of prayer” every first Monday of the month and urged his people to pray for him at sunset on Saturday evening and sunrise Sunday morning. And, in the summer of 1800, revival swept Kentucky.

McGready had three small congregations in Muddy River, Red River, and Gasper River in Logan County in the southwest of the state. Most of these people, who were refugees from all states in the Union, had fled from justice or punishment. They included murderers, horse thieves, highway robbers, and counterfeiters. The area was nicknamed Rogues Harbor.

Red and Gasper Rivers Revival

Four-to five-hundred people from McGready’s three congregations gathered with five ministers at Red River for a “camp meeting” in June 1800. On the last day of their meetings, God’s Spirit fell on them with mighty power. People fell to the ground, many crying out to God with screams for mercy. Word soon spread about these surprising events.

McGready and the other ministers immediately arranged another camp meeting in late July 1800 at Gasper River. The huge crowd that gathered, approximately 8,000 people, mostly in wagons, came from up to 100 miles away.

McGready described one of the evening meetings where a Presbyterian minister preached to the multitude by the flickering glow of faming torches:

The power of God seemed to shake the whole assembly. Toward the close of the sermon, the cries of the distressed arose almost as loud as his voice. After the congregation was dismissed the solemnity increased, till the greater part of the multitude seemed engaged in the most solemn matter. No person seemed to wish to go home—hunger and sleep seemed to affect nobody—eternal things were the vast concern. Here awakening and converting work was to be found in every part of the multitude; and even some things strangely and wonderfully new to me (Christian History 1989, 25).

These frontier revivals became a new emphasis in American revivalism. By 1802 these outdoor gatherings, combined with camping in tents and wagons, were called “camp meetings.” They spread across the frontier settlements. Meetings in the open, or in large tents, featured fiery evangelists. The sawdust trails—laid down to settle the dust or soak up the moisture on the ground—became paths where repentant sinners made their way to the front of the meetings, often with tears or loud cries of anguish.

© Geoff Waugh. Used by permission.

For further Research:

James McGready

Red River Meeting House