Ulster Revival 1623

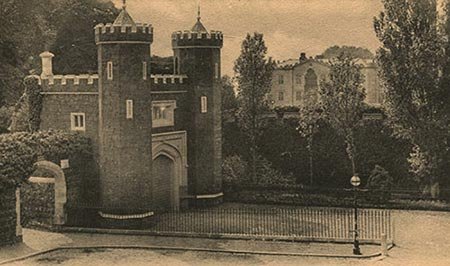

Antrim Castle

The success of the Reformation from the first was much slower in Ireland than in either of the sister kingdoms.

Few Protestant ministers were settled in the country, and these for the most part very ill qualified for the discharge of their duties; while the government, bent upon a favourite scheme of discontinuing the native Irish language, prohibited its use in the service of the church—permitted no books to be printed in that language, and even directed that in those parishes where the English was not understood by the readers, the church service should be conducted in Latin.

With means so exceedingly inadequate it is not surprising that few of the people should have embraced the reformed doctrines, and that the country should have continued essentially Popish.

The condition of Ulster in the early days of the Reformation

The province of Ulster, in the early period of the reformation, was in a condition still worse than the other parts of the country. Those intestine wars which raged during the latter part of the reign of Elizabeth had their chief seat here, and had reduced the province almost to a state of depopulation. Most of the towns were destroyed; cultivation had nearly ceased; and the few proprietors who remained, supported themselves on plunder, and lived in a condition little better than barbarism.

In circumstances so very unfavourable the spread of Protestant principles could hardly be otherwise than small, and in fact they were scarcely known beyond a few of the principal towns, insomuch that in the beginning of the reign of James I., Du Pin, a Roman Catholic historian, describes the province of Ulster as “the most constant in maintaining its liberty and in preserving the Catholic religion.”

The greater part of the bishops and ministers were still Roman Catholics, and of the few Protestant ministers, who were scattered over the country, many were shamefully ignorant, and even scandalous in their lives. In many parishes there was no minister, and except in some of the principal towns and cities, divine service had not been performed in a single parish church throughout the province for years together.

King James’ plan for Ulster

To provide a remedy for this unhappy state of the country, King James projected a plan for planting it with settlers from England and Scotland.

Great part of the province had been forfeited to the crown during the rebellions, and from the forfeited estates liberal distribution was made for the encouragement of settlers; the King taking especial care, at the same time, to provide for the spread of religion, by repairing the churches and providing glebes for the ministers, as well as restoring the ecclesiastical possessions and endowing free schools for the revival of learning.

Archbishop James Ussher

Soon after this plan was set on foot the province began to assume a new aspect. The deserted cities were filled with inhabitants, towns were built and incorporated, the lands gradually cleared of woods, cultivation was resumed, and peace and industry were generally restored.

The sees were now all filled with Protestant Bishops, and a scriptural confession of faith, in which the intolerant spirit of the church of England was avoided, was drawn up by Dr. (afterwards Archbishop) Ussher, and adopted by the clergy; so that in the bosom of the church of Ireland many of the Puritans of England and Scotland, who had been driven, by persecution, from their native country, found a secure retreat, and were promoted to situations of honour and usefulness.

Among the most eminent of these were Mr. Edward Brice, formerly minister of Stirling, who was settled at Broadisland in the year 1613; Mr. Hubbard, an English Puritan minister, settled at Carrickfergus about the year 1621; Mr. John Ridge, a native of England, presented in 1619 to the vicarage of Antrim; Mr. Robert Blair, formerly one of the regents or teachers in the College of Glasgow, who came to Bangor in 1623; and Mr. James Hamilton, who was educated for the ministry in Scotland, and ordained at Ballywater about the year 1625.

No fear of God amongst the inhabitants

Before the arrival of these godly ministers the character of the settlers was far from being such as to encourage them in their labours, and indeed they were very generally openly immoral and profane. “From Scotland,” says Mr. Stewart, who was minister of Donaghadee in 1645, (* Footnote: For this and the subsequent extracts from a manuscript of Mr. Stewart, as well as for the preceding account of the state of Ireland, and much of what follows, we are indebted to the excellent History of the Presbyterian Church in Ireland, by Dr. Reid, of Carrickfergus.)

—”from Scotland came many, and from England not a few; yet all of them generally the scum of both nations, who, from debt, or breaking and fleeing from justice, or seeking shelter, came hither, hoping to be without fear of man’s justice, in a land where there was nothing or but little as yet, of the fear of God. And in a few years, there flocked such a multitude of people from Scotland, that these northern counties of Down, Antrim, Londonderry etc., were in a good measure planted, which had been waste before.

Yet most of the people were all void of godliness, who seemed rather to flee from God in this enterprise than to follow their own mercy. Yet God followed them when they fled from him. Albeit at first it must be remembered, that as they cared little for any church, so God seemed to care as little for them.

For these strangers were no better entertained than with the relics of Popery, served up in a ceremonial service of God, under a sort of antichristian hierarchy, and committed to the care of a number of careless men, who were only zealous to call for their gain from their quarter; men who said “come ye, I will bring wine, let us drink, for tomorrow shall be as this day, and much more abundant.”

Thus, on all hands atheism increased, and disregard of God, iniquity abounded with contention, lighting, murder, adultery, &c. as among people who, as they had nothing within them to overawe them, so their ministers’ example was worse than nothing, for, from the prophets of Israel profaneness went forth to the whole land. And verily at this time the whole body of this people seemed ripe for the manifestation, in a great degree, either of God’s judgments or mercy.

For their carriage made them to be abhorred at home in their native land, insomuch that going for Ireland was looked on as a miserable mark of a deplorable person. Yea, it was turned into a proverb, and one of the worst expressions of disdain that could be invented was, to tell a man that “Ireland would be his hinder end!”

The efforts of the early preachers in the Ulster Revival

The labours by which the English and Scottish ministers above named endeavoured to establish the gospel among this ungodly people, were most zealous and unremitting. Some idea of them may be formed from the account given by Mr. Blair of his own labours in the parish of Bangor.

“My charge,” says he, “was very great, consisting of about six miles in length, and containing above 1200 persons come to age, besides children, who stood greatly in need of instruction.

This being the case, I preached twice every week, besides the Lord’s day. But finding still that this fell short of reaching the design of a gospel ministry, and that the most part continued vastly ignorant, I saw the necessity of trying a more plain and familiar way of instructing them; and therefore, besides my public preaching, I spent as much time every week, as my bodily strength could hold out with, in exhorting and catechising them.

Not long after I fell upon this method, the Lord visited me with a fever; on which, some who hated my painfulness in the ministry, said scoffingly, that they knew I could not hold out as I began. But in a little space it pleased the Lord to raise me up again, and he enabled me to continue that method the whole time I was at Bangor.”

The marvellous effects of prayer

To these labours, Mr. Blair and his brethren joined much fervent prayer. Mr. Blair’s acquaintance, with Mr. Cunningham of Holywood was comfortable to them both, and they frequently visited one another, and spent many days and hours together in prayer and godly conference.

The effects were soon apparent. A spirit of religious inquiry was excited among the people, ignorance began to be dispelled, careless and secure persons were aroused to a sense of their danger, the immoral were reclaimed to habits of decency, and the general aspect of the country became marvellously changed.

At Bangor a considerable reformation was effected, and, a short time afterwards, a more general awakening appeared in the neighbourhood of Oldstone, where James Glendinning, a native of Scotland, and formerly Lecturer at Carrickfergus, had lately settled as minister.

Carrickfergus Castle

The origin and progress of the awakening

Of the origin and progress of this awakening Mr. Stewart has preserved the following Account. “Mr. Blair,” says he, “coming over from Bangor to Carrickfergus on some business, and occasionally hearing Mr. Glendinning preach, perceived some sparkles of good inclination in him, yet found him not solid but weak, and not fitted for a public place, and among the English.

On which Mr. Blair did call him, and using freedom with him, advised him to go to some place in the country among his countrymen; whereupon he went to Oldstone (near the town of Antrim) and was there placed. He was a man who would never have been chosen by a wise assembly of ministers, nor sent to begin a reformation in this land.

For he was little better than distracted; yea, afterwards, did actually become so. Yet this was the Lord’s choice, to begin with him the admirable work of God; which I mention on purpose that all men may see how the glory is only the Lord’s in making a holy nation in this profane land and that it was ‘not by might nor by power, nor by man’s wisdom, but by my Spirit, saith the Lord.’

At Oldstone, God made use of him to awaken the consciences of a lewd and secure people thereabouts. For seeing the great lewdness and ungodly sinfulness of the people, he preached to them nothing but law-wrath, and the terrors of God for sin. And in very deed for this only was he fitted, for hardly could he preach any other thing.

But behold the success! For the hearers finding themselves condemned by the mouth of God speaking in his word, fell into such anxiety and terror of conscience that they looked on themselves as altogether lost and damned; and this work appeared not in one single person or two, but multitudes were brought to understand their way, and to cry out, men and brethren, what shall we do to be saved!

I have seen them myself stricken into a swoon with the word; yea, a dozen in one day carried out of doors as dead, so marvellous was the power of God smiting their hearts for sin, condemning and killing. And of these were none of the weaker sex or spirit, but indeed some of the boldest spirits who formerly feared not with their swords to put a whole market town in a fray; yet in defence of their stubbornness cared not to lie in prison and in the stocks; and being incorrigible, were as ready to do the like the next day.

I have heard one of them, then a mighty strong man, now a mighty Christian, say that his end in coming to church was to consult with his companions how to work some mischief. And yet at one of those sermons he was so catched, that he was fully subdued. But why do I speak of him? We knew and yet know, multitudes of such men who sinned and still gloried in it because they feared no man, yet are now patterns of sobriety, fearing to sin because they fear God.

And this spread through the country to admiration, especially to that river, commonly called the Six-milewater, for there this work began at first. At this time of people’s gathering to Christ, it pleased the Lord to visit mercifully the honourable family in Antrim, so as Sir John Clotworthy, and my lady his mother, and his own precious lady, did shine in an eminent manner in receiving the gospel, and offering themselves to the Lord; whose example instantly other gentlemen followed, such as Captain Norton, of whom the gospel made a clear and cleanly conquest.

The work of God advances

“When, therefore, the multitude of wounded consciences were healed, they began to draw into holy communion and meeting together privately for edification, a thing which in a lifeless generation is both neglected and reproved. But the new life forced it among the people, who desired to know what God was doing with the souls of their neighbours, who, they perceived, were wrought on in spirit, as they had been.

There was a man in the parish of Oldstone, called Hugh Campbell, who had fled from Scotland; him God caught in Ireland, and made him an eminent and exemplary Christian until this day. He was a gentleman of the house of Duket-hall. After this man was healed of the wound given to his soul by the Almighty he became very refreshful to others who had less learning and judgment than himself.

He therefore invited some of his honest neighbours who fought the same fight of faith, to meet him at his house on the last Friday of the month; where and when, beginning with a few, they spent their time in prayer, mutual edification, and conference on what they found within them, nothing like the superficial superfluous meetings of some cold-hearted professors, who afterwards made this work a snare to many.

But these new beginners were more filled with heart exercise than head notions, and with fervent prayer rather than conceity gifts to fill the head. As these truly increased so did this meeting for private edification increase too; and still at Hugh Campbell’s house, on the last Friday of the month.

At last they grew so numerous, that the ministers who had begotten them again to Christ, thought fit that some of them should be still with them to prevent what hurt might follow.”

Accordingly, adds Mr. Blair, “Mr. John Ridge the judicious and gracious minister of Antrim, perceiving many people on both sides of the Six-mile-water awakened out of their security, made an overture that a monthly meeting might be set up at Antrim, which was within a mile of Oldstone, and lay centrical for the awakened persons to resort to, and he invited Mr Cunningham, Mr. Hamilton, and myself, to take part in that work, who were all glad of the motion, and heartily embraced it.

This meeting was continued for many years. In the summer days four did preach; and when the day grew shorter, only three: And through the Lord’s blessing on our labours, religion was spread throughout that whole county, and into the borders of some others. Mr. Glendinning was at the first glad of the confluence of people, but we not having invited him to bear a part in the monthly meeting he became so emulous, that, to preserve popular applause, he watched and fasted wonderfully.

Afterwards he was smitten with a number of erroneous and enthusiastic opinions, and at last he set out on a visit to the seven churches of Asia.”

Visits of Josiah Welsh, Henry Colvert, George Dunbar, John Livingston and Andrew Stuart

Having lost this instrument, others more worthy were afterwards through the good providence of God, added to the ministry. “From Scotland,” says Mr. Blair, “came over Mr. Josiah Welsh, son of the famous Mr. John Welsh, who both in Scotland and France was instrumental in converting and confirming many. A great measure of that spirit which wrought in and by the father, rested also upon the son.

The last time I had been in Scotland, I met with him, and finding of how zealous a spirit he was, I exhorted him to hasten over to Ireland, where he would find work enough, and I hoped success too. And so it came to pass: For Mr. Welsh having been settled at Temple-Patrick, became a great blessing to that people. Next Mr. Henry Colvert, an Englishman, helper to Mr. Edward Bryce at Broadisland, was settled at Oldstone.

This able minister having been of a fervent spirit, and vehement delivery in preaching, and withal very diligent, he was a blessing to that people. And after these two the Lord brought over to Lochlarne old Mr. George Dunbar, after he had been deposed from his ministry at Ayr by the High Commission, and banished by the Privy Council. At Larne the Lord did greatly bless his ministry, and he and the other two having joined the monthly meeting, the word of God grew mightily, and his gracious work prospered in our hands.”

Antrim Castle on the Six Mile Water

About the year 1630, Mr. John Livingston, assistant at Torphichen, having been oppressed by the bishops, went over to Ireland, where he was ordained at Killinchie. “Being a man of a gracious melting spirit he did much good, and the Lord was pleased greatly to bless his ministry.” Much about the same time Mr. Andrew Stuart, “a learned gentleman and fervent in spirit,” was settled at Dunagor, where his ministry was successful during the short time he lived.

The work of conversion spreads

The blessed work of conversion, which was of several years’ continuance, had now spread beyond the bounds of Antrim and Down to the skirts of neighbouring counties; and the resort of people to the monthly meeting and communion occasions, and the appetite of the people, were become so great, that the ministers were sometimes constrained in sympathy to the people to venture beyond any preparation they had made for the season.

“And indeed, preaching and praying were so pleasant in those days, and hearers so eager and greedy, that no day was long enough nor no room great enough to answer their strong desires and large expectations.” The following very interesting particulars are given by Mr. Livingston, in his Memoirs. Referring to his settlement at Killinchie, he says,

“Although the people were very tractable, yet they were generally very ignorant, and I saw no appearance of doing any good among them; yet it pleased the Lord that in a short time some of them began to understand somewhat of their condition.

Not only had we public worship free of any inventions of man, but we had also a tolerable discipline; for after I had been some while among them, by the advice of heads of families, some ablest for that charge were chosen elders to oversee the manners of the rest, and some deacons to gather and distribute the collections.

Strict rules for the impenitent

We met every week, and such as fell into notorious public scandals, we desired to come before us.

Such as came were dealt with both in public and private to confess their scandal, in presence of the congregation, at the Saturday’s sermon, before the communion, which was celebrated twice in the year,—such as would not come before us, or coming would not be convinced to acknowledge their fault before the congregation, upon the Saturday preceding the communion, their names, scandals, and impenitency were read out before the congregation, and they debarred from the communion, which proved such a terror that we found very few of that sort.

We needed not to have the communion oftener, for there were nine or ten parishes within the bounds of twenty miles, or little more, wherein there were godly and able ministers, that kept a society together, and every one of these had the communion twice a-year, at different times, and had two or three of the neighbouring ministers to help thereat; and most part of the religious people used to resort to the communions of the rest of the parishes.

Monthly prayer and fasting days

Most of all these ministers used ordinarily to meet the first Friday of every month at Antrim, where was a great and good congregation, and that day was spent in fasting and prayer, and public preaching. Commonly two preached every forenoon and two in the afternoon. We used to come together the Thursday night before and staid the Friday night after, and consulted about such things as concerned the carrying on of the work of God; and these meetings amongst ourselves were sometimes as profitable as either presbyteries or synods.

And out of these parishes now mentioned, and some others also, such as laid religion to heart, used to convene to these meetings, especially out of the Six-mile-water, which was nearest hand, and where was the greatest number of religious people. And frequently the Sabbath after the Friday’s meeting, the communion was celebrated in one or other of these parishes.

True unity of heart

Among all these ministers, there was never any jar or jealousy, yea nor amongst the professors, the greatest part of them being Scots, and some good number of very gracious English; all whose contention was to prefer others to themselves. And although the gifts of the ministers were much different, yet it was no observed that the people followed any to the undervaluing of others.

Many of these religious professors had been both ignorant and profane, and for debt and want and worse causes, had left Scotland, yet the Lord was pleased by his word to work such a change, I do not think there were more lively and experienced Christians anywhere, than were these at that time in Ireland, and that in good numbers,

And several of them, persons of good outward condition in the world; but being lately brought in, the lively edge was not yet gone off them. and the perpetual fear that the bishops would put away their ministers, made them with great hunger wait on the ordinances.

I have known them come several miles from their own houses, to communions, to the Saturday’s sermon, and spend the whole Saturday night in several companies, sometimes a minister being with them, sometimes themselves alone, in conference and prayer, and then they have waited on the public ordinances the whole Sabbath, and spent the Sabbath night likewise, and yet at the Monday’s sermon they were not troubled with sleepiness, and so have not slept till they went home.

Because of their holy and righteous carriage, they were generally reverenced even by the graceless multitude among whom they lived. Some of them had attained such dexterity at expressing religious purposes, by the resemblance of worldly things, that being at feasts and meals in common inns, where were some ignorant and profane persons, they would among themselves entertain a spiritual discourse for a long time, and the others professed that although they spoke good English, they could not understand what they said.

In those days it was no great difficulty for a minister to preach or pray in public or private, such was the hunger of the hearers, and it was hard to judge whether there was more of the Lord’s presence in the public or private meetings.”

Systems of discipline

The system of discipline referred to by Mr. Livingston, was the same as that observed in Mr. Blair’s congregation, of the beneficial influence of which, in connexion with the faithful preaching of the word, Mr. Blair narrates the following instance.

“A cunning adulterer who had continued long in that sin before I went to Bangor, and by bribing the bishop’s official had concealed his wickedness, having been present at a sermon which I had on the parable of the Sower, it pleased the Lord so to reach his conscience, that he made confession of his great sin with many tears, and sought to be admitted to the public profession of his repentance.

This the session readily agreed to, and he appeared publicly for several days, under very deep conviction, to the great affecting of the congregation, and lived ever after a reformed man so far as could be perceived.”

The Devil’s attempts to derail the revival by physical manifestations

There were now many converts in all the congregations which have been mentioned, and Satan observing the prosperity of the gospel amongst them set himself to perplex them by discrediting the work of God in their hearts. This he did by a counterfeit of the operation of the Holy Spirit on several persons at Lochlarne, whom he caused to cry out during public worship, and some of them were affected with convulsive pangs.

The number of persons thus affected increased daily, and at first the ministers and people pitied them, hoping that the Holy Spirit was at work with them. But when they had conversed with them, and found that they did not discover any sense of their sinful state or any longing after a Saviour, the minister of the place wrote to his brethren, inviting them to come and examine the matter, who when they had spoken with them saw that it was a mere delusion of the destroyer.

The next Sabbath, an ignorant person in Mr. Blair’s congregation made a noise, but immediately, says Mr. B., “I was assisted to rebuke that lying spirit which disturbed the worship of God, and I charged the same in the name and authority of Jesus Christ, not to molest that congregation; and through God’s mercy we met with no more of that sort.”

Accusations against the ministers

Having thus been foiled in this attempt Satan now made a handle of his own device to stir up enemies against the faithful ministers. Archbishop Ussher’s Confession of Faith had by this time been laid aside, and the ritual and ceremonies of the English Church having been adopted in its stead, the former moderation of the bishops was no longer continued.

The ministers who had been most successful in promoting the work of reformation were accused to them of teaching that bodily convulsions were necessary to the new birth, and the bishop of the diocese at first suspended four of them from their labours; and then, after a short relaxation, obtained for them by Archbishop Ussher, he deposed all the four from their sacred office.

The conduct of the people on this occasion strikingly illustrates the spirit of prayer which abounded among them. Mr. Blair having set out to London, with the view of obtaining a trial for himself and his brethren, “left many holy persons, wrestling with God for a comfortable issue. And indeed,” says he, “they were a praying people for whom I undertook this journey.

At my house two nights were spent every week in prayer; and though those who did bear chief burden therein were not above the rank of husbandmen yet they abounded in the grace and spirit of prayer. Other places were not short of, but rather excelled in that duty, and even in congregations who yet enjoyed their own pastors, many prayers were put up on our account, as I learned at my return.”

When Mr. Blair returned, with a favourable answer from the King, the trial was still delayed, but the ministers continued to meet and pray with their people, until at the end of a twelvemonth they obtained a licence to preach publicly for six months. So great was Mr. Blair’s astonishment at the news of this unlooked-for liberty that he did not sleep for three nights afterwards.

The first, he says, was wholly spent in admiring the goodness of God; the second in thanksgiving with his people, who solemnly prayed with him; and the third he spent in preparation for his stated lecture, which occurred on the succeeding day. When he resumed this lecture he found a large congregation, not only of his own flock, but of many from neighbouring congregations; who, on hearing the gospel again publicly preached, were melted down into tears of joy.

A time of freedom and peace for a short period

The monthly meeting at Antrim was also resumed, to the inexpressible joy of the people, and public worship being now freely permitted, they made more progress in the ways of the Lord than ever before. This liberty was however of short continuance. Mr. Blair and Mr. Dunbar, were soon deposed a second time from their office, and they concluded their ministry by celebrating the Lord’s supper, and solemnly delivering up their flocks to the great Bishop of souls from whom they had received their sacred office.

Five of the other ministers were afterwards deposed, and the work of revival was for a time much impeded. The number of the godly was, however, very considerable, many of whom, along with some of their ministers, came over to Scotland to escape the violence of the persecution which followed.

The revival ministry goes underground

This persecution proceeded from the adherents of Episcopacy, who, headed by the haughty and cruel Earl of Strafford, imposed such heavy fines, and inflicted so severe imprisonments upon the Presbyterians, for refusing to take the oaths prescribed to them by government, that while many of the ministers were forced to leave the country those who remained dared not preach publicly.

They still however continued to meet privately with their people, and usually in the night time, for religious worship. And even when most of the ministers had fled to Scotland, and the more timid of those who still remained were afraid to attend these proscribed assemblies, such laymen as were most distinguished for their knowledge and piety conducted the worship of the people, and expounded the scriptures for their mutual edification and comfort.

By these means the knowledge and love of the truth were preserved among multitudes, until they again had an opportunity of statedly hearing the gospel from the lips of their ministers, while others held the ministers in so great veneration that many of them removed to Scotland for the sole purpose of enjoying their ministry.

Of those who remained large numbers came over from Ireland to attend the stated dispensation of the Lord’s supper in the parishes where they were settled. On one occasion no fewer than 500 persons visited Stranraer, that they might receive ordinances from the hands of Mr. Livingston.

A second persecution stops the progress of the Revival

This first persecution was soon followed by a second of a more bloody and disastrous character, at the Rebellion of 1641—of which all classes of Protestants were the subjects, so violent, that in a small part of Ulster alone about thirty ministers were cruelly massacred by the papists.

These disasters put a check for the present to the progress of the Revival. In Scotland the ministers and people who had fled thither for refuge, were kindly treated by the people of God, and hid as it were in the hollow of His hand, until the times of slaughter and persecution had in some measure passed away.

After a few years most of them returned to their adopted land; and along with the chaplains of the Scottish army, and many of the ministers, who had formerly adhered to Episcopacy, were the means of planting in Ulster the Presbyterian Church, which to the present day continues to flourish in that province.

A summary of the preaching

Among the means by which this extensive work of grace was promoted, the Christian character of the ministers, and their faithful and diligent preaching, hold a prominent place. The following particulars of their style of preaching may be added to what has already been said.—

Of Mr. Brice, Mr. Livingston informs us, “that in all his preaching he insisted most on the life of Christ in the heart, and the light of his word and Spirit on the mind, which was his own continual exercise.” “Mr. Ridge,” he says “used not to have many points in his sermon, but he so enlarged those he had, that it was scarcely possible for any hearer to forget his preaching. He was a great urger of charitable works, and a very humble man.”

Mr. Blair’s labours have already been particularly referred to. “He was a man,” says Livingston, “of notable constitution both of body and mind; of a majestic, awful, yet affable and amiable countenance and carriage, thoroughly learned, or strong parts, deep invention and judgment, and of a most public spirit for God. His gift of preaching was such, that seldom could any observe withdrawing of assistance in public, which in others is frequent.

He seldom ever wanted assurance of his salvation. He spent many days and nights in prayer alone and with others, and was vouchsafed great intimacy with God.”

Of Mr. Welsh, we are informed by the same writer, that “he was much exercised in his own spirit, and therefore much of his preaching was an exercise of conscience and Mr. Blair adds, “He did with great eagerness convince the secure, and sweetly comfort those who were dejected.” “Mr. Stuart,” says Livingston, “was a man very straight in the cause of God.” Of Mr. Colvert, he says,

“He very pertinently cited much scripture in his sermons, and frequently urged private fasting and prayer.” Mr. Livingston himself was the minister who was honoured when a young man to preach the famous sermon at the Kirk of Shotts, which was followed with so rich a blessing. He was one of the most learned and laborious among the brethren.

In summary

Connected with the preaching of the gospel, it appears from the foregoing narrative, that the strict and impartial exercise of discipline—the frequent practice of public and private fasting—the fellowship and godly conferences of Christians— and above all, a spirit of earnest prayer, hold a prominent place among the means of promoting this revival.

These means were all of the most scriptural kind, and without them it would be presumptuous to expect an extensive revival of religion.

Let then those amongst us who desire to obtain a similar out-pouring of the Spirit of grace imitate the example of these followers of Christ—let the gospel be preached, with application to the consciences of men as sinners.

And let it be adorned by the lives of those who profess to receive it—let the discipline of the Church be impartially and vigorously administered—the practice of fasting and social prayer revived, and a spirit of enlarged intercession and supplication cherished—and then indeed may we hope to see the windows of heaven opened, and a blessing poured out “till there shall not be room enough to hold it.”

Surely this is a blessing worthy of being asked, and if sought for the result is not doubtful. The Saviour himself has assured us that if we “being evil know how to give good gifts to our children, much more will our heavenly Father give his Holy Spirit to them that ask Him.”

“Ask, and ye shall receive, seek, and ye shall find; knock, and it shall be opened unto you, for I say unto you that every one that asketh receiveth, and he that seeketh findeth, and to him that knocketh it shall be opened.” “For as the earth bringeth forth her bud, and as the garden causeth the things that are sown in it to spring forth, so the Lord God will cause righteousness and praise to spring forth before all the nations.”

This article is a chapter from Narratives of Revivals of Religion in Scotland, Ireland and Wales published in 1839.

Check out these links for further research

Free download of ‘The Ulster Revival’ by Matthew Kerr